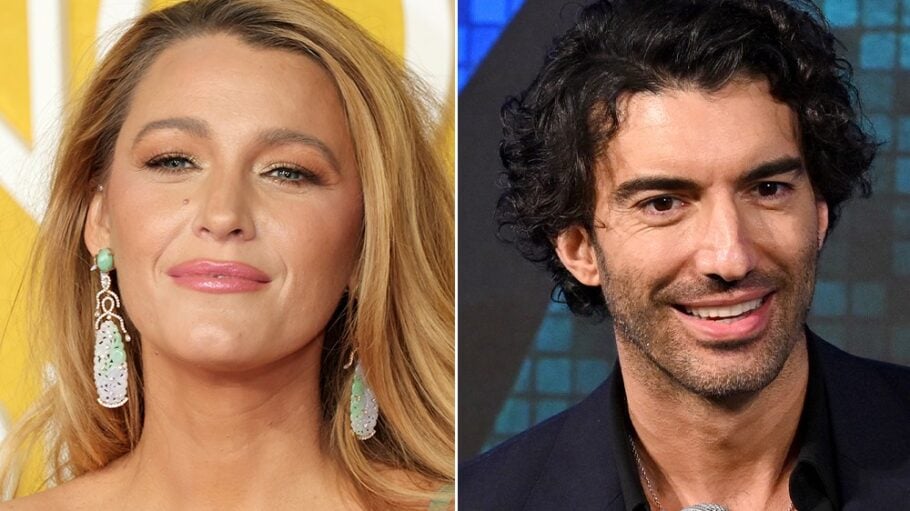

The scene is a crowded bar. Director Justin Baldoni says that his co-star, Blake Lively, looks “pretty hot.” Lively says that wasn’t her aim.

“Sexy,” Baldoni says, in mock self-correction. “Sorry, I missed the sexual harassment training.”

That interaction, captured on video, seems like fodder for a future Human Resources webinar. For now, it is one piece of Lively’s sprawling lawsuit against Baldoni and others involved in “It Ends With Us.”

The case, now pending before a federal judge, has offered a mother lode of celebrity gossip. But it also tests the line between discriminatory behavior and creative freedom, and has the potential to set new standards for acceptable conduct on Hollywood sets.

The last time this issue was explored so thoroughly, in 2006, creative freedom won. The California Supreme Court threw out a suit involving graphic sexual talk in the “Friends” writers’ room. In that case, Hollywood united behind the “Friends” writers, arguing that however offensive it might appear to outsiders, such speech was essential to the creative process.

The reaction to Lively’s suit has been more divided, mostly along the lines of personal loyalty. But in his defense, Baldoni’s lawyers have invoked the “Friends” precedent, arguing that some amount of sexual commentary is inherent in making a sexually charged film. The case, Lyle v. Warner Bros., still stands, but a lot has changed in the culture since 2006.

“I think if my case had arisen after the #MeToo movement, there might have been a different outcome,” said Amaani Lyle, the former writers’ assistant who filed the suit. “The case was ahead of its time.”

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

Her lawsuit described conduct that it would be hard to imagine being condoned today. The “Friends” writers would fantasize about sex with Jennifer Aniston and Courtney Cox, tell stories about receiving oral sex, sketch nude cheerleaders, call women “cunts,” and propose storylines about Joey raping Rachel in the shower. Lyle, who is Black, also alleged that the writers, who were white, would dip into “ghetto talk,” which she found degrading.

At the time, the Writers Guild of America argued that a writers’ room is “not an insurance office,” and that lawyers and juries should not be allowed to intrude.

“Not only would this make a mockery of the First Amendment, but it would effectively spell the end of network television as we know it,” wrote Marshall Goldberg, the union’s general counsel, in an amicus brief co-signed by Norman Lear, Larry David, Steven Bochco, Diane English, and other TV legends.

Though the case is remembered as a victory for creative freedom, Lyle argued that a great deal of the behavior had nothing to do with work.

“It was truly brilliant marketing on the side of Warner Bros.,” she said.

Officially, Warner Bros. had a zero tolerance policy toward harassment. An HR manager testified that interpretation was flexible: “We don’t take it very literally… because in every work environment it’s different.”

Wayfarer Studios, which made “It Ends With Us,” has a similar policy, strictly forbidding sexual “comments, stories, or innuendos” as well as sexual remarks about someone’s clothing or appearance. And as co-chairman of Wayfarer, Baldoni had in fact attended the HR training where the policy was discussed.

Lively’s attorneys have argued that Baldoni violated that policy by oversharing about his sex life, talking about his porn addiction, and pushing for intimate scenes that she wasn’t comfortable with. Her breaking point came when Wayfarer CEO Jamey Heath, unprompted, showed her a video of his wife giving birth.

“I think the actions that I’m describing are pretty obviously sexual harassment,” Lively said in her deposition.

But the company policy exists to protect the company – not to create a standard by which it can be sued. The bar for actionable harassment, set by the Supreme Court 40 years ago, is comparatively high.

Misconduct must be so “severe or pervasive” that it alters the conditions of employment. The California Supreme Court ruled that the “Friends” conduct did not reach that level. U.S. District Judge Lewis Liman is applying the same test as he decides how much of Lively’s case will go to a jury.

In private messages released in court filings, Baldoni seems distressed and baffled by Lively’s allegations, at one point chalking them to his neurodivergence. “Most anything that I have been accused of is social awkwardness and impulsive speech,” he wrote in a text.

Yet however righteous they may feel, employers routinely settle cases that fall short of the “severe or pervasive” standard.

“That is the culture that employers face now,” said Jared Slater, a partner at Ervin Cohen & Jessup. “Employers don’t have the time or the expense to try and roll the dice with a judge and jury.”

Baldoni and Lively are relatively rare in their willingness to bear the costs of full vindication. The parties showed up on Wednesday for a court-mandated mediation, but were not able to reach a deal.

Lyle, meanwhile, left the industry long ago for a career in the U.S. Air Force. She saw “It Ends With Us” and liked it.

But she’s not taking sides.

“They each have a lot more leverage than I did as woman of color, very low on the food chain,” Lyle says. “Ultimately, they will both be OK.”

From Variety US