Think back to the greatest concert you ever saw — it could be Springsteen or U2 or the Stones, or Lady Gaga or the Ramones, or Taylor Swift or Radiohead, or (in my case) two concerts from the ’80s (Prince and X) and one from the 2000s (Madonna on her Confessions tour). Now think back to the greatest moment in that concert, the one that gave you chills you can still feel. That’s the kind of experience I predict you’ll have watching “EPiC: Elvis Presley in Concert,” an extraordinary new documentary directed by Baz Luhrmann, the director of “Elvis.”

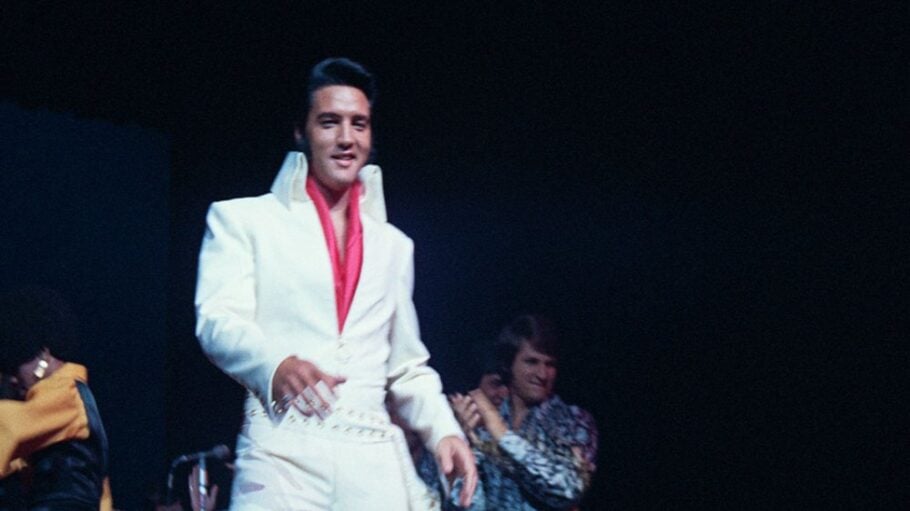

The movie is a revelation, because for 96 minutes it shows you just how intoxicating Elvis Presley was when he began to perform live in Las Vegas in 1969 and the early ’70s. Many don’t quite think of him that way. There’s still a mythology hanging over Elvis during this period — the Vegas glitter, the white suit with the half-sun cape, the giant finger rings and the car-grille sunglasses, the “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”-from-“2001” bombastic musical intros, the sweat pouring off his shag-carpet sideburns, the onstage karate moves. It can all add up to a vision of the king of rock ‘n’ roll presiding over a kingdom of kitsch.

But there’s the myth and there’s the reality, which has always been incredible, and there are reasons why the perception of that reality has evolved over time. I can hardly overstate the degree to which in the ’70s, the simple fact that Elvis was performing in Las Vegas was thought of as unspeakably cheesy; it wasn’t what rock performers did. His outfits seemed a parody of grandiloquent fashion camp, and the fact that he would sing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” right along with “Hound Dog” and “Don’t Be Cruel” made him seem like some cornball Americana nostalgia act.

So what’s changed? In the age of Vegas residencies (not just Gaga but the Grateful Dead!), Elvis’s Las Vegas gigs now look startlingly ahead of their time. The taint of it all has melted away. (Vegas is no longer the place where vulgar “Middle Americans” go; it’s the place where everyone including hipsters go.) And in the age of fashion as postmodern excess, where stars are now expensive exhibitionists, Elvis’s straight-Liberace costumes, in their quite intentional loud-and-proud spangled peacock gaudiness, no longer look like something anyone would even think of ridiculing; they have the glam audacity of true…rock ‘n’ roll. (It’s Jimmy Page, in his comfy sweaters, who now seems dated.) Elvis, in the early ’70s, was still relatively lean and mean, and still incandescent to look at. He was in his regal mid-thirties, with those sexy dimples and one of the greatest heads of hair in rock history. And that voice! His tremolo vibrato made every note into a pearly gem.

Seven years ago, when “Bohemian Rhapsody” came out, I went back and watched a lot of footage of Queen in concert, because I wanted to key into Freddie Mercury, who is now universally thought of as one of the most electrifying performers in the history of rock. He deserves that reputation. But I’m here to testify that he’s about one-third as electrifying as Elvis was in the early ’70s. The power of Elvis’s voice remained undiminished — it soared, it quavered, it caressed, it boomed, it rocked, it hit every note with singular beauty. And though he would sometimes flirt with comedy in his moves, and didn’t jiggle the way he did in 1956, the way he held and moved his body still possessed a flamboyant erotic eloquence.

Luhrmann originally planned to incorporate never-before-seen footage of this period into “Elvis,” and decided against it. But what he discovered, at the time, was 68 boxes of 35mm and 8mm footage in the Warner Bros. archives, including vast outtakes from the “Elvis: That’s the Way It Is” (1970) and “Elvis on Tour” (1972), the two major Elvis concert films, plus audiotapes of unheard interviews. Much of the footage was silent (though there was corresponding audio), and it all needed to be painfully synced up, a process that took two years. Diving into this treasure trove of unseen performances, working with the editor Jonathan Redmond, Luhrmann has fashioned a streamlined and exquisitely paced concert film. Narrated by Elvis (from the interview clips), it incorporates rehearsal footage from when he was getting ready to play Vegas for the very first time at the International Hotel (offstage, we see what a perfectionist Elvis could be, and also what a charmingly modest and gregarious hang-out buddy), and it interpolates numerous performances from his Vegas residency, almost all of them from the early ’70s.

Elvis performed more than 1,100 shows from 1969 to 1977, and at a certain point, when the drugs and the overeating were taking their toll, he did start to slide into a parody of himself. But not in the early years. And watching that vintage period now, we feel the life-force charge of what Elvis still had, which is very connected to what he had in 1956, but also different. When you see footage of Elvis in the ’50s, from “Ed Sullivan” or wherever (“EPiC” includes some never-before-seen footage of his legendary “gold lamé concert” from Hawaii in 1957), you’re seeing two things at once: a staggeringly great performer, but also a man who with every hip shake and lip curl was changing the karma of the world. That’s not an exaggeration, and it’s baked into the original Elvis experience.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

The ultimate inaccurate cliché is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s statement that “there are no second acts in American life.” (He was really talking about himself.) Elvis Presley had one of the greatest second acts in history, and it began in 1968, when he had his legendary network-TV comeback special. Lurhmann opens “EPiC” with a long and dazzlingly edited summary of Elvis’s career, notably the movies, which were indefensible but in a certain way underrated. (They were kitsch, but even the worst of them were highly watchable kitsch.) But there’s no doubt that Elvis had faded as a musical force. Starting in the late ’60s, he returned with a vengeance, and what was telling is that the meaning of his style and the meaning of his presence had shifted. He was no longer a rebel; you can’t be one after you change the entire world into something created in your image. But what that meant, since we were no longer plugging into the volcanic revolutionary side of his sexual swagger, is that we now experienced him purely as…a pop and rock musician.

The movie warms up with the rehearsal footage, where we see him, in a blindingly colorful super-psychedelic shirt, do haunting renditions of the Beatles’ “Yesterday” and “Something,” and also Dusty Springfield’s “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me.” We hear Elvis talk about how he cherishes all kinds of music — how as a teenager he would listen to Mario Lanza and the Metropolitan Opera. The “soft” side of Elvis has always been major. But shortly after that, he’s onstage singing “That’s All Right,” and the reason it doesn’t feel like nostalgia is that the song’s velocity is ramped up — it now sounds like a bullet train. Elvis was backed by a group of musicians, known as the TCB Band (for Taking Care of Business), that totally kicked. James Burton’s guitar solos are blistering, and when Elvis stands onstage and plays air guitar along with them, it’s a thrill, because it’s less corny than loosely choreographed abandon.

Elvis and the band do a “Hound Dog” that’s so fast it’s punk. He sings “Polk Salad Annie” (“Her mama was working on the chain gang…”) with a gritty momentum worthy of Tina Turner, and in a very cool hybrid he segues back and forth between “Little Sister” and “Get Back.” And in a sequence guaranteed to give you those chills, we see him perform “Burning Love,” one of his two greatest songs from that era, for the very first time (he’s still reading the lyrics off a sheet of paper), and it just about burns the house down.

Elvis also fools around a lot: He fellates the mic, he mocks the lyrics, he sings with a bra on his head (he got tossed a lot of those), and Luhrmann, picking up on this spirit, offers his own bit of mockery by accompanying Elvis’s performance of “You’re the Devil in Disguise” with a montage of Col. Tom Parker, who we also glimpse in the concert standing just behind Elvis as he works his way through the crowd of adoring women. Did Parker deserve the bad rap that Lurhmann gave him in “Elvis”? Peter Guralnick’s new book argues otherwise, but I think Guralnick misses the forest for the trees. Elvis, as he himself explains in the documentary, was passionate about his desire to perform in other countries (which he never once got to do), and if that one thing had been allowed to happen, I believe the whole trajectory of his life might have been different.

“EPiC” climaxes with a surly-sublime version of “Suspicious Minds,” an indescribably great song that could almost be the battle hymn of a republic that had attained a 50 percent divorce rate. And when the movie is over, you want to applaud the showmanship: Elvis’s, and also Baz Luhrmann’s. He reveres Elvis too much to let any excessive flash get in the way. There’s a purity and natural-born dazzle to “EPiC.” What you see is what you get: Elvis in the raw, driven by the awareness that it doesn’t get any better than that.

From Variety US