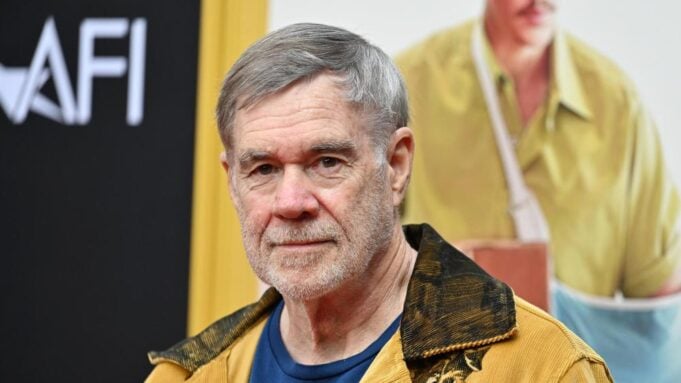

Gus Van Sant is still moving.

“I think a lot of the films I’ve made, even unintentionally, have been based on real things,” Van Sant says with his familiar mix of understatement and curiosity. “That’s a genre, I guess. I’ve always been drawn to what makes people do what they do.”

In “Dead Man’s Wire,” Van Sant’s latest film, which premiered at AFI Film Festival on Saturday, that fascination becomes electrified — literally. The historical true-crime drama, based on the real-life 1977 Tony Kiritsis hostage case, unfolds like a pressure cooker between desperation and spectacle.

“When I read the script,” he recalls, “there were links embedded in it — you could click them and hear the real 911 calls. Tony talked so fast, like Scorsese on a cocaine bender, cracking jokes and losing his temper. I thought, ‘This is an amazing character.’”

Van Sant’s words carry a quiet thrill, the sound of an auteur who has spent a career balancing empathy and danger. From “Drugstore Cowboy” and “My Own Private Idaho” to the Oscar-nominated “Good Will Hunting” and “Milk,” he’s never chased a single genre; only human behavior.

“The story had this weird barnstormer energy,” he shares. “We were meeting in the Soho House, and the producer said, ‘We have to start shooting in Louisville in two months.’ That was the most appealing thing — just hitting the road like Huckleberry Finn.”

Now 73, Van Sant is nostalgic when talking about creative chaos. “The best thing about film is still the accident,” he says. “River Phoenix used to love when something unexpected happened on set. He’d come alive inside those moments — he could feel his character reacting in real time.”

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

That memory lingers, as does the one of the fog machines at the 1998 Oscars that made him physically ill while “Good Will Hunting” (1997) lost most of its awards to “Titanic.”

“I’m allergic to stage fog now,” he says with a chuckle. “So I never use it on set.”

It’s been seven years since his last theatrical film (“Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot”), but Van Sant is back with a story that echoes his fascination with real American tragedy and absurdity — a director drawn, as ever, to the ragged edge between empathy and obsession.

With “Dead Man’s Wire,” Van Sant delivers his most arresting and charged work since “Milk.” The film hums with the restless energy that defined his early 1970s-like masterpieces while showcasing a sharpened maturity in tone and control. Skarsgård gives a career-best performance, grounding Tony Kiritsis’ volatility with flashes of humor and heartbreak, while Dacre Montgomery and Colman Domingo deliver richly textured performances. Dark horses for the Oscars? Of course. But that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be considered. In particular, Van Sant’s direction is at once intimate and explosive, framing the chaos with empathy, allowing the audience to feel the pulse of desperation behind every decision. The film’s screenplay, adapted from real events by first-time screenwriter Austin Kolodney, is infused with humanism and dark wit, standing as one of the year’s finest.

In a wide-ranging interview with Variety, Van Sant talks about his past, present and future in the industry he’s spent over four decades mastering.

Stefania Rosini SMPSP

Looking at your filmography, this fits with your interest in real-life characters and crimes.

Yeah, I think so. A lot of my films, even the fictional ones, are based on something from the real world — a news story or an article. “Drugstore Cowboy,” “Elephant,” and “Last Days” all came from that impulse. It’s not “true crime” like television, but it’s about what makes someone act a certain way — that question inside the crime.

How did you settle on Bill Skarsgård for Tony and Dacre Montgomery for Richard?

Casting was probably as important as the script. I was at a spa one weekend, listening to ambient music, trying to decide if I should jump into this project immediately — we had to start shooting in November. I’d always wanted to work with Bill. I’d offered him roles before that didn’t happen. He has this fascinating career — horror films, yes, but he’s like Lon Chaney, the man of a thousand faces. He’s also 10 years younger than the real Tony, which made it interesting.

Dacre I knew because of his audition tape for “Stranger Things.” It’s one of those legendary tapes actors pass around — perfect lighting, perfect eyelines. I didn’t even watch the show at first, just his scenes. He felt new, unpredictable, and that was what the movie needed.

And Colman Domingo as the radio DJ — it’s such an inspired choice.

We actually modeled that character after the DJ in “The Warriors.” That was in the script. We had a few actors pass before Colman came aboard. He was working with our producer, Cassian Elwes, on another project and said, “I’d love to work with Gus.” He was perfect — his presence grounds the film.

Fans always ask if you’d ever revisit “Drugstore Cowboy.”

Actually, there are screenplays that the same writer wrote — James Fogle. There were four different ones, and one of them is called “Satan’s Sandbox,” that I think James Franco wanted to do, but that was the one I kind of preferred. It’s set in San Quentin prison. And actually, when we met him and made the movie, he was in Walla Walla State Penitentiary in Washington State, and so he had some stories when they were out of prison, like “Drugstore Cowboy,” when they were running around, selling drugs and stealing drugs. So there are other ones, yeah, there are other ones that exist.

River Phoenix was so prolific in your cinema journey. He definitely is one of the core reasons I, myself, fell in love with movies. How often does he cross your mind?

I mean, I think about him all the time — there’s a picture on the wall of him. He was sort of like, you know, a very great collaborator. And we only did that one piece, and we were planning on — he was planning on being in what turned out to be “Milk.” But that didn’t happen till later, before he died, so there was a project that we were talking about. But, yeah, he was very spontaneous. He loved to improvise. That was his favorite thing. And I don’t think he got to, necessarily, depending on who he was working with, go off the page and improvise. It probably wasn’t the type of films that he was doing — he was doing traditional pieces that were pretty much, like, securely in Hollywood. You know, he was doing traditional pieces, that’s what he was offered.

And in that environment, you’re not making a film like — you know, like you’re mentioning Scorsese — where they improvise whole scenes. And when we did, he found out that I liked it, you know, that I was okay if he just did something for like five minutes that wasn’t even in the screenplay, because then he could actually research stuff, and he could feel very open about what he was playing. So that was kind of magical, that he liked it, and he had not been able to do it. So he was very excited about it, because he wasn’t normally doing it.

I don’t know, there’s lots of things. His upbringing was such that he didn’t really have a lot of film history connected to his memory banks. He was homeschooled, so he didn’t have a lot of teaching that he knew about concerning war. His homeschooling consisted of, like, no war. So characters like General MacArthur weren’t in his world — he didn’t know who they were. And then conversely, he didn’t know what humor was. He didn’t know what, like, a quote-unquote joke was, until he was nine, he said.

He found that out because he went to a traditional school — a public school — and kids were telling jokes. It was an era when kids were all about jokes. He didn’t know what they were; they were just like a foreign thing to him. He also didn’t have a smile, which people don’t necessarily know. He told me that — he said, ‘Well, I don’t have a smile.’ And I said, ‘You’re kidding.’ And then he smiled and showed me his smile, and I said, ‘Oh yeah, I don’t see that smile in your films.’

So he had this interesting thing — for a movie star, an interesting absence of that kind of giant smile. But meanwhile, he was very funny, and his most favorite thing was just to laugh and tell stories.

You’ve been nominated twice for an Oscar. What do you remember about those mornings?

Mostly that I didn’t realize when the announcements were happening. I woke up to a bunch of phone calls. It’s the big Hollywood prize — it feels great. At the ceremony for “Good Will Hunting,” they unveiled this huge Titanic ship set, and fog rolled out everywhere. I got so sick sitting there, I swore I’d never use fog on my sets again.

There’s a lot of talk about the “death” of cinema. Do you believe that?

Not at all. Movies always follow technology — from nickelodeons to iPhones. What matters is the gathering, that communal experience. The art form isn’t dying; it’s just shifting. The best films of the 1920s were miracles because nobody knew what cinema was yet. We’re in another one of those periods of discovery.

Can we expect another film soon? Or do we have to wait another seven years?

I hope so. I did the Gucci project and six hours of “Feud,” so I haven’t been idle. There are hundreds of ideas — digital files full of them. Some might take decades, like “Milk” did. But they’re there, waiting.

From Variety US