Earlier this year, Colman Domingo and a few girlfriends took a trip to New Orleans. They were there to attend Essence Fest, one of the world’s largest celebrations of Black culture, so it shouldn’t have come as a surprise that the star of “Zola” and “The Color Purple” and “Rustin” was flanked by fans all weekend long.

Still, Domingo’s posse were thrown as they noticed which heads, in particular, were turning. “I had become, in many ways, a heartthrob for Black women,” he says now, unable to mask his satisfaction at the thought — he’s married to a man, and has never tried to hide that. “They were hugging and kissing on me, and some even whispered, ‘I know you don’t play for our team, but I have a crush on you.’”

He’s making a point: “I said, ‘You can still have a crush on me! I still want you to think I’m hot and sexy, and I’ll flirt with you too. We don’t have to limit ourselves.’ Because I never limited myself. I’ve imagined myself having wives and children and husbands and everything.”

That imagination has guided Domingo through a wide-ranging career that began in the theater more than 30 years ago. Then, in 2015, he made his on-screen breakout playing Victor Strand, a villainous con artist who eventually seeks redemption in AMC’s “Fear the Walking Dead.” By the time the show concluded in 2023, he was everywhere. “Euphoria,” for example, won him an Emmy for offering tough love to Zendaya’s Rue as sobriety sponsor and recovering addict Ali. And just last year, he became only the second openly gay actor after Ian McKellen to earn an Oscar nomination for playing a gay character, this time in “Rustin,” which he led as the titular Civil Rights activist.

Those roles set the stage for what has become his most important and most personal performance yet. In “Sing Sing,” released by A24 in July, Domingo stars as a playwright incarcerated after being wrongfully convicted of murder. Leading the cast as one of only three professional actors — the rest served time at the prison the film is named for — Domingo is once again a favorite in the awards race. If he wins voters’ hearts again in January, he’ll become the first openly gay actor (and the second Black actor after Denzel Washington) to earn Oscar nominations in back-to-back years. But the work doesn’t stop there.

In exhaustive and exhausting detail, Domingo lays out his upcoming plans as we sit having breakfast on the rooftop of a swank members-only club in Los Angeles. They range from his first-ever half-hour comedy series to the two films he’s set to direct: One is a Nat King Cole biopic he’ll also star in, and the other follows the love story between Kim Novak and Sammy Davis Jr. There’s also “The Madness,” a Netflix thriller series starring Domingo as a CNN pundit who must clear his name of murder accusations, premiering on Nov. 28. And maybe another season of “Euphoria.” I’m beginning to lose track of all of his projects, and I say so.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

“Oh, really?” Domingo replies, practically batting his eyelashes, unembarrassed to ask me to expand on my compliment. So I oblige, and he lets out the same coy giggle he did while regaling me about the effect he had on the straight women of New Orleans. Because as Domingo pictures the many wives he could have wed at Essence Fest, it’s not just the fact of their desire that thrills him; it’s that they won’t ever know him. And neither will I. Not really.

That air of mystery began with a few lies on his résumé.

Of course, he prefers to spin it differently. “I began my career with some version of the truth,” he says, but there’s a flash of mischief in his grin as he settles into this tale.

“I met with this woman who gave professional guidance for people who wanted a career in the theater. She was fabulous,” he tells me. It was the early ’90s, and he’d just landed in San Francisco from his hometown of Philadelphia when he discovered the job coach’s ad in a magazine. “I like to believe that she was wearing a Chanel jacket. And very well-appointed earrings,” he says. “She was very well put together, and she had a little bob, and she was a white woman.”

Domingo stops himself, bringing his hands together in a single clap. “I’m remembering all of this right now! I’ve never told anyone this,” he says, delighted. I almost don’t believe him. Not only is each beat of the story told with enough polish to feel pre-written, but there’s choreography: a hand swirling under his jaw to illustrate this woman’s look, a straightening of his posture as he puts on her voice. Then again, these theatrics are present throughout the two hours I spend with Domingo. The man knows how to tell a story.

“She asked me about my experience, of which I had none. But then she asked me about my interest, of which I had plenty,” he continues. “And she told me about the steps to becoming a professional.”

“Always wear a watch as a young man, because it signals that you’re concerned about time,” Domingo recalls the woman telling him. He places an elbow on the table in front of him and nods at the elegant black TAG Heuer on his wrist.

“Always dress a bit neutral, a bit opaque, so people can see you playing anything,” the woman continued. At this stage of his career, Domingo is seen as something of a fashion icon. He’s dressed in all black today — aside from the silver Prada logo over his left breast.

And crucially: “She said, ‘Take a speech class for your dialect.’ Because I’m sure I had some very regional Philadelphia accent; I was saying ‘jawn’ and things like that,” he says, barely able to remember a time he’d speak in his hometown slang instead of using the word “thing.”

Indeed, this detail is hard to imagine. The deliberateness of Domingo’s speech is his signature quality as an actor: Every consonant is crisp and every vowel is sung, making every word feel carefully chosen. There’s a certain humor and whimsy to his voice, in the fluctuations of his pitch especially, but altogether, it feels placeless.

“Then she helped me fluff up my résumé, and things I had taken in class became overblown and a bit of a lie,” he says, grinning again. Short scenes performed in Temple University lecture halls transformed into full-fledged productions staged by local playhouses. And with them, a Philly-bred college dropout debuted as the newest darling of the Bay Area theater scene.

Domingo hadn’t intended to become an actor. At Temple, he started out studying journalism. “I wanted to go to war-torn places and connect with people and tell their stories,” Domingo says. “That’s what I wanted to do. But I was really close to failing this class.” Week after week, a journalism professor stamped his reporting as “too creative,” a critique he had no idea what to do with.

“She said my writing was too florid, whatever that means,” Domingo says, teeth ripping into a slice of gluten-free toast. Ever polished, this is the only moment in two hours when Domingo speaks with food in his mouth; perhaps, subconsciously, it’s a dig at that teacher. “I was like, ‘Florid? What is that? Flowers?’ I don’t think I even looked it up. I still don’t know what it means.”

Domingo seems to have noticed that he’s fixating on something that should no longer matter, because at once, his brow loosens and he bursts out laughing. “I was just so frustrated,” he says. “Like, ‘Apparently, I’m not doing this right.’”

Domingo’s mother, Edith Bowles, encouraged him to try an acting class as an elective, and when that first drama teacher told him he might have a future onstage, it was Edith who suggested that he drop out of school. “She said, ‘Take some time off. Get yourself together,’” Domingo recalls. So he moved to San Francisco, cramming in as the fourth roommate in a tiny studio apartment.

He soon met the man who would become his best friend. Back then, Sean San Jose was just another kid looking for work; today, he’s Domingo’s co-star in “Sing Sing” and the creative executive of the company Domingo launched in 2020 — Edith Productions, in honor of his mother, who died in 2006.

Remembering their first meeting, at an audition, San Jose laughs and says, “Colman had a goofy little backpack on, and he was in shorts, looking all cute — this humble, sweet, clearly mama’s boy from Philadelphia. We instantly connected.”

That boyish vibe was something they recognized in each other early on. “We both grew up sweet on our mothers, and maybe too soft to be heroes or tough guys or leading men,” San Jose says.

But Domingo is a leading man now, and still just as “soft” as he was in San Francisco. In “Sing Sing,” Domingo plays John “Divine G” Whitfield, one of the founding members of an in-prison theater program called Rehabilitation Through the Arts. Based on a 2005 Esquire article, the film follows the men of RTA as they produce an original play with Divine G as their de facto leader. In between the moments he spends teaching the group about Shakespeare and Stanislavski , Divine G tries to keep his peers out of trouble and tirelessly prepares for his own upcoming parole hearing. But this isn’t, to Domingo, “a prison film in any way.”

Instead, it’s a gentle, moving portrait of male friendship. “I don’t think I made a ‘Shawshank Redemption’ or ‘Cool Hand Luke,’ you know?” he says. “The container is a prison, but it’s about the people inside. It’s about people making art and having breakthroughs in their lives.”

The heart of “Sing Sing” is the platonic affection that blooms between Divine G and Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin. Director and co-writer Greg Kwedar describes Divine Eye as “the kind of friend” who, for Divine G, “comes in and reveals parts of yourself that you didn’t know needed loving.”

That love had its genesis off-screen. The first time Domingo met Maclin, who plays himself in “Sing Sing,” the two were reviewing the script with Kwedar. Maclin explained their characters’ shared nickname to Domingo: the “Divines” are a prison fraternity of sorts, and joining their ranks binds you to a certain code of conduct.

During this conversation, Domingo broke a major rule of the brotherhood. “I was being colloquial: ‘N—-, this, that, blah-blah.’” Delicately, Maclin stopped him. “‘We don’t use “n—-.” No. When you are Divine, you use the word “beloved.”’”

Domingo makes the sound of a bomb going off. “My head exploded,” he says.

As Kwedar remembers it, “Colman just burst into tears. Then he turned to me and said, ‘That has to be in the film.’” And it was: In a moment of complete emotional devastation for Divine G, it’s Divine Eye calling him “beloved” that brings him back to life.

Domingo is still clinging to “beloved” two years later. As a philosophy, that word may be the force that makes his performance in “Sing Sing” so memorable. Previous roles have tasked Domingo with soaring monologues and sweeping physicalities, but in his portrayal of Divine G, there’s an understated quality he hasn’t gotten many chances to show us. That naturalism wouldn’t be possible without the genuine sense of intimacy he developed with Maclin and the other formerly incarcerated men he made the movie with.

In the film, and in their real lives before it, Domingo’s castmates used acting to heal from their traumatic prison experiences together. Rehearsals required them to show up with sincerity. “They were holding space to be tender, and they were being held accountable for that tenderness,” Domingo says. He’s still moved by that idea, remarking, “I never see that image of masculine Black and brown men being tender with each other.”

But the sensitivity the “Sing Sing” cast shared is still nearly too much for Domingo to bear. He’s only seen the film once. “At home, where I was safe,” he says, his voice suddenly so low I can barely hear it. “I was alone.”

Dominic Leon

“Sing Sing” is the rawest Domingo has ever felt on camera, he tells me, and his body is still connected to it. While promoting the film at festivals and awards events, he skips the screening portion of the night, slipping back into the auditorium as the credits roll. “When I watch it, I’m feeling whatever I was feeling, and I know that’s not useful when I need to do a talk-back with an audience. I can’t be going out there all emotional.”

He hears how that sounds after all his talk of tenderness, and lets out a groan. “I don’t know! I don’t know what that feels like. I don’t — maybe — I don’t know. I feel —” he says, stumbling. Domingo is perhaps best known for his eloquence, but here, he’s caught in a loop, grasping for the right thing to say.

Then he slows down, finding his way back to his argument. “I don’t want to overindulge. And I don’t want it to be about me or my tears or my feelings. I want to acknowledge yours,” he says, tapping on the table between us. “And maybe I’m wrong. Maybe I need to go out there a little more vulnerable. But I give so much in my work, and I feel like that’s my offering.

“Now, when I go out, I’m Colman Domingo, dressed in some style,” he says, the bass and confidence returning to his voice. “I can speak in a very well-practiced, very mindful way and not let my emotions override. There’s a certain amount of opaqueness that I think works.”

He’s gone back to the fabulous woman in San Francisco and her advice to employ a bit of illusion. “People notice that I dress very monochromatic. It’s a power move,” he says. “You can see me playing a king. You can see me playing a pimp. I’m not giving you all of me; I’m giving you an aspect of me that I want you to see.”

It’s not lost on me how deftly Domingo moved away from the subject of watching “Sing Sing” once it became too exposing. I say nothing, but he knows what I’m thinking, and when he opens his mouth to speak, his voice has changed again. This time, he’s left his singsongy-ness behind. “I feel like I’m giving you more of me than usual,” he says plainly.

Bottling his feelings, orating with panache, donning high fashion — it’s becoming clear that Domingo’s approach to celebrity is a means of keeping himself safe from an industry or an audience too keen to tell him what he’s capable of. That’s a shrewd strategy for any Black actor, especially one who’s freely embraced his queerness in public for the entirety of his career.

But his opacity is also a way to protect the projects he chooses, including the controversial ones.

Take “Euphoria.” Series creator Sam Levinson has been one of Hollywood’s favorite subjects of gossip since the HBO drama premiered in 2019; there are rumors of his feuds with actors and dysfunction as a director, while many take issue with his explicit depictions of teen characters’ bodies on-screen. The cast of “Euphoria” can rarely make it through a red carpet without fielding questions about Levinson, which may be why Domingo decides to bring him up without being prompted.

“People can rumor what they want about Sam’s practices, and I don’t really have a comment on that,” he says. “But I do have a comment on my own experience, which has been incredible. He will literally hand me the pen and say, ‘What do you think?’ That’s a true collaborator.”

As for his own involvement, Domingo says, “Apparently I will be back for Season 3. I don’t know anything about the scripts. I don’t know anything about the production date.” I remind him that HBO has said the show restarts shooting in January, and he guffaws, “I’ve heard it’s January. I’ve heard as much as you’ve heard, so we’ll see. But allegedly — that’s a great word to use, ‘allegedly’ — Ali is back. From what I’ve heard.”

And then there’s Antoine Fuqua’s upcoming Michael Jackson biopic, in which Domingo stars as patriarch Joe Jackson, whom Michael (played by the late pop star’s nephew, Jaafar Jackson) accused of physical and emotional abuse. “Michael” is produced by the executors of the Jackson estate, which maintains his innocence against the multiple allegations against him of child sexual abuse while exerting rigorous control over his public image.

The fact that “Michael” exists at all has already drawn significant backlash, and Domingo knows there will be more upon its release in 2025. “But anything surrounding those ideas about him never came into play with me,” he says. “It’s about the character, more than anything. And the idea of working with the estate, Antoine Fuqua and Jaafar Jackson — who is exceptional.”

Domingo claims that regardless of the estate’s involvement, the movie will look at the “complex human being” behind the pop icon. “I believe everyone has a story to tell,” he says.

That explanation won’t be enough for everybody, but Domingo is accustomed to a polarized response. “I come from the theater, and my job has always been to let the audience feel what it needs to feel.”

People were offended, he tells me, by the characters he played in Broadway musicals like “Passing Strange” and especially “The Scottsboro Boys,” which is famous for its use of blackface and minstrelsy. “But my job was not to be liked. My job was to tell the story,” he says. “It wasn’t about approval. And I’ve taken that to my film and television work.”

“When I backhanded Fantasia in a film,” Domingo says, referencing his role in “The Color Purple” as Celie’s abusive husband, Mister, “some people would say, ‘I’m gonna feel some kind of way about him.’ That’s OK. You should have a strong feeling about it, but hopefully it’s not about me as a person. When I played Victor Strand on ‘Fear the Walking Dead,’ people hated me on Twitter. Sometimes I would correct them: ‘You hate Victor Strand, which is fine. You don’t hate me.’ Because I don’t like that energy coming at me.”

But the reason people might fault him for acting in “Michael” isn’t that Joe Jackson is a difficult character — it’s that he, Domingo, has chosen to work with the Jackson estate. I point out that he’s conflating the two. Isn’t there a difference?

He thinks on it. “I don’t know,” he says truthfully. “I think I divorced myself from that early on.”

Domingo tugs at the bottom of his Prada jacket, smoothing it out. By now, I know it’s intentional that he’s drawing my eyes back to his all-black ensemble, to an image that’s hard to project on.

“I learned that I’m in service to the piece, not to the response,” he says. “That’s the only reason I can perform the way I do.”

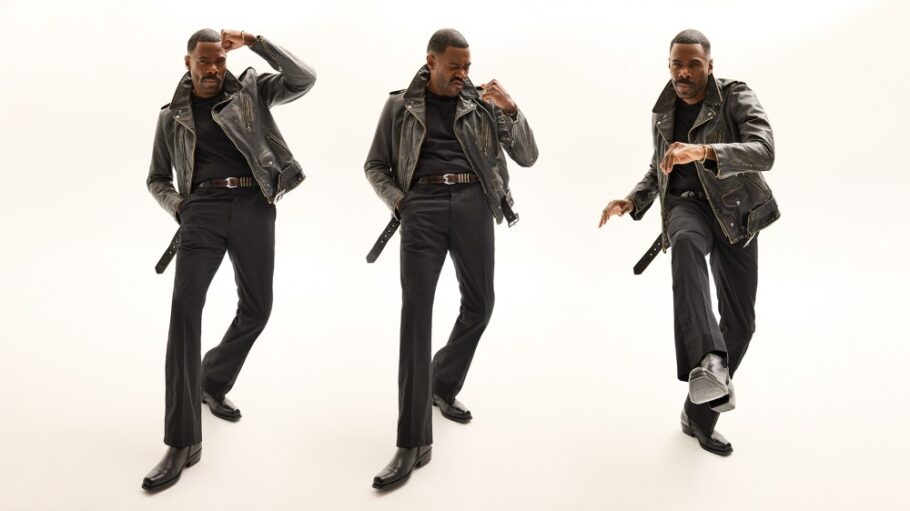

Styling: Alex Badia; Market Editor: Luis Campuzano; Grooming: Jessica Smalls/ A Frame Agency; Set Design: Desi Santiago/The Wall Group; Look 1 (3-full body portraits): Jacket: Schott; Shirt: Clark; Pants: Amiri; Belt and boots: Versace; Look 2 (cover): Blazer: Luigi Bianchi; Shirt: Giorgio Armani; Jeans: Sandro; Belt: Versace; Look 3 (red background): Turtleneck: Amiri; Look 4 (full body, trench coat): Coat: Emporio Armani; Shirt: Hermès; Pants: Amiri; Belt and boots: Versace; Look 5 (Coat: Ralph Lauren Purple Label; Boxers: Hanro; Pants: Louis Vuitton)

From Variety US