O.J. Simpson died April 10. But the media age ushered in by his presence, his saga and his white Bronco, remains very much with us.

An all-time great NFL running back-turned-actor, Simpson was a minor celebrity and part of a circle of fame-adjacent Los Angeles hangers-on in the 1990s. (Notably, Simpson’s close friends included the Kardashian family.) The killing of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ron Goldman, on June 12, 1994, converted Simpson instantly into an object of national obsession; five days later, Simpson failed to turn himself in after the Los Angeles Police Department ordered him to surrender on charges of first-degree murder, and engaged the LAPD in a low-speed car chase.

The details of this have been chewed over, including by the recent double dose of O.J. stories — FX’s series “The People v. O. J. Simpson: American Crime Story” and Ezra Edelman’s documentary “O.J.: Made in America,” both released in 2016 — and yet they still boggle the mind. The chase, which ended with Simpson’s surrender, had been presaged by the reveal of what was interpreted as Simpson’s suicide note. The reported 95 million people watching the chase unfold had no idea if the evening’s morbid entertainment — so riveting that it appeared as a picture-in-picture cutting into NBC’s coverage of the NBA Finals — would end in tragedy or with Simpson in handcuffs.

This live media sensation — which came years before L.A. local news outlets became consumed with car-chase coverage — set the tone for all of the coverage of the trial, and for Simpson’s life in public after it. Judge Lance Ito’s decision to allow television cameras into his courtroom turned each player in the trial (including and especially prosecutor Marcia Clark) into media celebrities, but it was Simpson, sitting at the center of it all, who had the highest voltage. The trial functioned as yet another low-speed chase — spanning from January to October of 1995, it unfolded methodically enough for daily viewers to savor its twists (with the infamous “if the glove doesn’t fit” moment a sweeps-week moment for the ages). All the while, viewers knew that at the end, one sort of catharsis or another awaited.

Simpson’s acquittal, dramatized by FX as a day of racial reckoning, read extraordinarily differently by Black and white trial-watchers, kicked off a new stage of his life. After his NFL days, the former USC star running back tried to go into sports broadcasting, and he pursued acting with significant roles in movies such as 1977’s “Capricorn One” and 1988’s “The Naked Gun” and its sequels. In the 1980s and early ’90s, he was all over TV as a pitchman for the Hertz car rental service and other products.

Once his blockbuster trial ended in 1995, Simpson was, once again, a celebrity hanger-on, but clinging to a very different kind of fame. And his continued attempts to convert his notoriety into money — in particular the horrific and tawdry media circus around the 2007 book “If I Did It” — cemented Simpson as a figure who might only be able to exist in America. The book, styled as a confession for crimes Simpson had always denied and explaining how Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman would have been killed, was met with outrage and disgust, and a planned interview special on Fox was cancelled. Simpson’s sheer ambition for finding the camera’s gaze, shamelessly choosing to play unaware of why it was he was being broadcast at all, made him an ideal cast member for the country’s ongoing reality show.

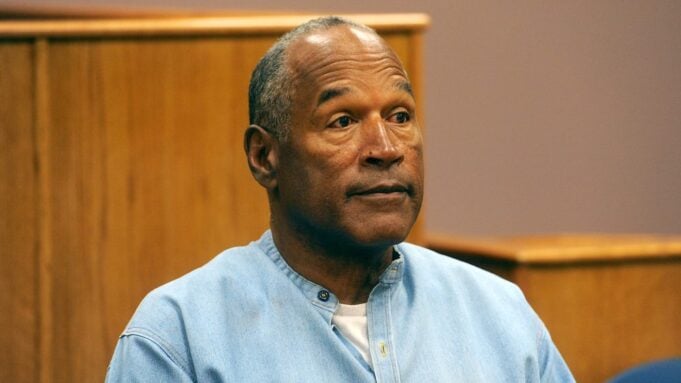

His eventual imprisonment was unrelated to the two 1994 deaths — he was convicted in 2008 of armed robbery and kidnapping in an odd, sad scheme to steal his own sports memorabilia from dealers. His nine-year sentence came as a result of Simpson’s obsessive desire to own his image, an image perhaps only he saw as worthy for reasons beyond scandal. After his 2017 release on parole, keeping up with Simpson became increasingly unsavory, as random videos of the man sharing his thoughts on various matters came to be a slow-news-day staple on TMZ. (In 2020, for instance, he begged golf courses to stay open during the COVID pandemic; coverage of a free Simpson golfing after his acquittal had long been a bugbear for those who believed he deserved to be in prison.) He was, at once, a figure whose long presence in American life, as it went on, felt to many like an increasingly irksome reminder of justice denied, and a say-anything card who didn’t mind being the butt of some dreadful joke as long as he got to stay on camera.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

All of which helped set the tone for the years after his trial. Simpson had, in his car chase, seemed to be in a state of extreme distress, but his unwillingness to turn himself in looks, in the context of the rest of his life, like presence of mind, not madness. For those hours, he was, preposterously, evading trouble and prolonging freedom simply by dint of his unwillingness to slow down. The lessons our culture learned from this were found in the watching: Millions upon millions absorbed that the news is best told as an endlessly rollicking, celebrity-fueled drama, and that those who make the news could find their best advantage by treating their role in it as that of a star finding their light. Every day — at least since the two Simpson projects first aired, in the consequential year of 2016 — is a slow-speed car chase. And we’re all riveted.

FROM THE VARIETY ARCHIVES

From the June 24, 1994, edition of Daily Variety

From Variety US