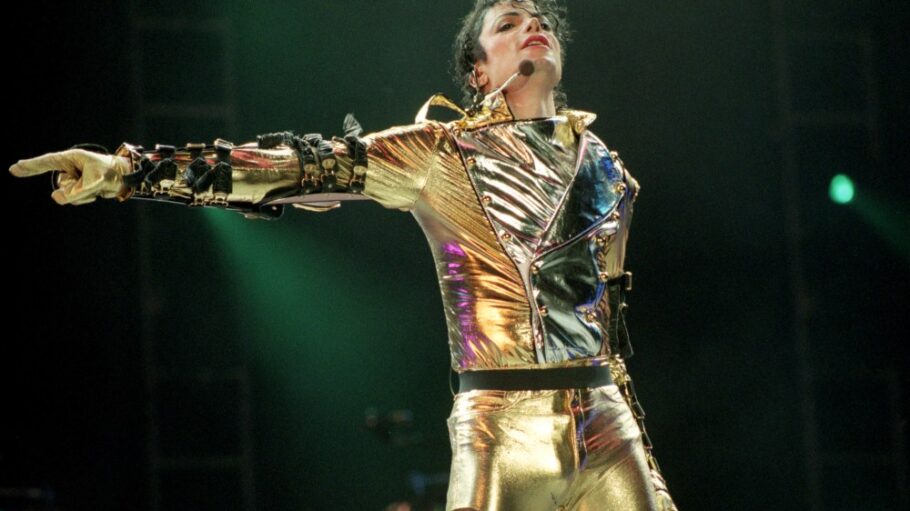

Could a superstar as big as Michael Jackson be compelled, almost against his will, to return to the recording studio for a do-over on one of his songs? The answer to that in 1995 was a surprising yes, when Jackson re-recorded a key line of the song “They Don’t Care About Us,” amid a media firestorm over controversial lyrics that included anti-Jewish slurs. But, maintaining that there was no antisemitic intent to his words, the superstar was far from happy about having to “make that change.” Indeed, he took out his anger on the recording studio where the vocal overdubs were taking place.

That’s one of the compelling stories in “You’ve Got Michael: Living Through HIStory,” a new book by former Epic Records executive Dan Beck, which offers a first-hand, never-before-revealed look at what was going on with Jackson’s music career during some of his peak years as the world’s biggest pop superstar in the 1990s. Beck, a senior VP at the company, worked closely with Jackson on the “Dangerous” and “HIStory” projects and bears fascinating witness to the ups and downs that marked that volatile period of change in Jackson’s life as well as stardom.

In Variety’s exclusive excerpt from “You’ve Got Michael,” Beck recounts exactly how reluctant Jackson was to change the lyrics to a recording that was already out in the marketplace, and the silent protest he registered after being convinced he had to. Published by Trouser Press Books, the book is available as a paperback and e-book online from Amazon, B&N, Apple, www.trouserpressbooks.com and other digital platforms. Here is the excerpt of a story recounted in Beck’s absorbing backstage memoir. —Chris Willman

– – –

Once Michael deemed the “HIStory” album complete, we set up a secure listening room at Sony Music Studios on West 52nd Street. Listening sessions were usually scheduled in the four or five weeks leading up to the release date and only select people were invited to a preview.

I attended nearly all of those listening sessions when I was not traveling. The first three or four were early evening “rehearsals” to make sure the album would sound perfect in this small studio. It was at one of those that I discovered the lyric issues of “They Don’t Care About Us.” The song had an aggressive, staccato beat and vocal delivery; the general theme was Michael as an oppressed underdog fighting back. On one of those first evenings, I heard a red flag as Michael angrily spat out the words, lyrics that included an antisemitic slur.

I told [my boss, Epic Records chairman] Dave [Glew] that somebody needed to speak to Michael and [Michael’s co-manager] Sandy [Gallin]. Sandy argued that Michael spoke as an empathetic voice of the oppressed. “He’s saying stop labeling people, stop degrading people, stop calling them names. The song is about not being prejudiced. To take two lines out of context is unfair.”

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

On Thursday, June 15, one day before the international in-store date and five full days before the U.S. street date, the controversy hit the fan. The New York Times, in an Arts section story under Bernard Weinraub’s byline, led the pack with the headline “In New Lyrics, Jackson Uses Slurs.” The first sentence established the issue: “…includes a song with lyrics that can be interpreted as pointedly critical of Jews.”

The controversy was already brewing behind the scenes, as Diane Sawyer had asked about the lyric in her taped interview with Michael and Lisa Marie for ABC News’ “Primetime Live,” which was scheduled to air that night. Sawyer’s spotlight, which sixty million people tuned in to see, gave Michael a national forum to clearly define his intent and lead the discussion with a measured response. Unfortunately, his reply was muddled: “It’s not antisemitic because I’m not a racist person. I could never be a racist. I love all races.” Worse, he fell on the weak and damning defense of “My accountants and lawyers are Jewish. My three best friends are Jewish — David Geffen, Jeffery Katzenberg and Steven Spielberg.”

Geffen and Spielberg were mixed in their responses. David offered a supportive perspective: “There’s not one iota of antisemitism in Michael. He’s not a hater of any kind. At worst, sometimes he’s naïve, and I think to the degree that anybody is bothered or offended, he’s genuinely sorry.” But Spielberg was angry and distanced himself from Michael. He had written liner notes for the album but now said, “[Those liner notes, written two years ago] are by no means an endorsement of any new songs that appear on what has now been released as Michael Jackson’s ‘HIStory’ album.”

We had three phone calls with Michael regarding the situation, and his answer was repetitive and straight to the point. “This is the media,” he complained. “I would never be racist or antisemitic.” We continued to explain that it wasn’t about him. It was about the people who those words hurt, no matter the context in which they were used.

He couldn’t grasp how the media could misunderstand his intentions. Instead, he saw a conspiracy against him. “People know I would never mean that!” he protested to me directly over the next few days. His voice was firm and steadfast: raised, but in control, yet he was clearly on the defense. His repeated response of “Everybody knows me. They know I don’t hate people” stood in stubborn defiance.

It was four days before the U.S. in-store date, and we had no idea how to defuse the issue. Suddenly, I was in meetings and on conference calls with Epic and Sony Music brass, with Sandy Gallin and with Michael’s stable of PR guns. Rat Pack veteran Lee Solters mixed it up with Motown alumnus Bob Jones, the vastly more contemporary public relations expert and strategist Michael Levine and the street-savvy New York-based media master Dan Klores. Meanwhile, critical voices roared out. [My assistant] Joy Gilbert fielded calls from Jewish organizations, including the Anti-Defamation League. “We got a huge backlash from that,” she remembers, “and it got worse after he went on with Diane Sawyer.”

We needed to speak with Michael. He was in the lead here and was going to do whatever he was going to do. We could give him information on our read of the media and the public reaction. We could give him advice on how to handle it. But ultimately, we needed to assess his position and then decide how to respond.

The meeting began with Michael protesting, “Everybody knows I’m not prejudiced!” In his mind, he had become the Jew in the song. It was he who was oppressed. It was he who spoke for the others. He wouldn’t hurt anyone. He still seemed bewildered that anyone could think otherwise. He went on to blame the media for ganging up on him, as it had done with the change of skin color, the plastic surgery and the child molestation accusation.

As the call progressed, it became clear that, by focusing on his adversaries, he had lost sight of those who were hurt or offended by the lyrics. Michael’s co-manager Jim Morey took a calm, rational approach, explaining that for the good of all he just needed to re-record the lyric. Finally, he agreed. I recall his response was a soft, resigned, almost inaudible “Okay.”

I actually felt bad for him. He believed he was capitulating to the media for a transgression that he didn’t commit. He saw this song as a protest, and he was the voice of that protest, not the antagonist. Yet his delay in making the change had backed us into a corner. Before ending the conference call, Michael agreed to re-cut the vocal at the Sony Music Studios.

Jim Morey [and I] continued to communicate, but it seemed that the King of Pop was avoiding the situation. After months of middle-of-the-night calls, Michael was now avoiding me on the phone. After repeated tries, I finally reached him. Michael knew why I wanted to speak with him. I had never called out Michael Jackson before, but that day I did just that. I reminded him that he had given his word, that an official press release had gone out saying he was re-recording the lyric. I told him how bad this looked. I said that I had spoken to every angry major journalist [including Army Archerd of Variety] and assured them all that he had personally told us he was making the change.

I never raised my voice, but I was as direct as I could be. He knew that I always gave him my honest thoughts. He knew that I didn’t shield him from the facts when he needed them. Whether under duress or not, Michael had made a promise, and I had conveyed that message on his behalf. He couldn’t just blow this off. I didn’t say so, but I was pissed. He needed to deal with this.

Jim Morey and Dave Glew were on the call. It was Jim who gently moved the debate into a path forward. “Michael, it would be easy for you to slip into the Sony studios when you are back in New York and re-do the lyric.” Dave added, “Michael, we can have this set up for you and put this issue behind us.” Michael heeded the groupthink. He softly gave in.

Within forty-eight hours, Jim Morey brought Michael to Sony Studios on 54th Street and 10th Avenue. It was shortly after the July 4th holiday, at least three weeks after the controversy arose. It seemed like a year! I greeted Jim and said, “Hi, Michael,” but Michael didn’t return the greeting. He was ticked! Jim quietly said hello as our eyes met in acknowledgment of how heavy this was.

We wove our way through the hallways to the bowels of the five-story building. Again, Michael never said a word, I guess to show Jim and me how angry he was. The tension was palpable, but at least the pace of our walk made it bearable. A recording engineer was waiting at the console in the control room. Michael, still silent, went directly into the studio, where a lone microphone and music stand stood.

Michael pulled a folded piece of paper from his pocket and placed it on the music stand. The engineer asked through the talk-back system if Michael was ready. Michael told the engineer to play the song from beginning to end. When “They Don’t Care About Us” reached the controversial lyric, the engineer pushed “record” and Michael sang the new lyric.

As the engineer let the song play on to another section that needed to be fixed, Michael picked up the music stand and threw it at the wall. He picked up a chair and threw it, too, then angrily pushed over a baffle. Michael Jackson was trashing the studio!

I looked at the engineer, who was clearly in shock. The cameraman, who was capturing the event so that we could carefully edit it and release a clip to the media to prove the change had been made, was frozen with his camera running. I saw his eyes bulge. But he never stopped filming.

As the song reached the second appearance of the controversial lyric, Michael went from maniacal anger back to smoothly singing the new lines. Once the recording light was off, he resumed the demolition of the studio.

Jim Morey and I looked at each other in the control room in disbelief, but with relief that we had gotten this task done. We simply started laughing. I think neither of us could believe the convoluted path this entire episode had taken. The engineer and cameraman looked at us like we were crazy.

Yes, we were crazy, all right! We had gone crazy trying to get this horrible controversy resolved — and now we had. We had it on the master tape and we had film footage to prove it. And Michael knew that he could express his anger to us, the footage of which would never get out into the world. I’ve never seen that video since the day after we shot it. There are various renditions of the song on YouTube, including those with the original lyric (listed as “uncensored”) and the revised version. The footage of Michael recording the new words was used only as part of the press release to announce that Michael had changed the lyrics.

The song finished playing. Michael ended his tirade and walked out of the studio. We left the control room and spilled out into the hallway. No one spoke. The three of us walked down the hall together to the lounge where we had met Michael. We said goodbye. And that was it.

In time, the lyrical controversy faded, but it was never really resolved. Michael believed in his heart that he had only wanted to represent the victims of tyranny. The media and the public took two roads: to believe him or to remain skeptical. I am quite sure the revised version of “They Don’t Care About Us” was used only for the single release and the promo videos but never implemented in a second manufacturing run of the album, as the factory already had an abundance of inventory. A later version simply had a sound effect added to obscure the words.

– – –

Dan Beck spent two decades at Epic Records as a publicity executive, product manager, and Senior VP of Marketing and Sales. He spearheaded marketing and media strategies for Michael Jackson, the Clash, Cyndi Lauper, Gloria Estefan, Sade, Luther Vandross, Pearl Jam, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Tammy Wynette, Charlie Rich, Cheap Trick, Ted Nugent and Boston, among many others. He later helped launch V2 Records for Virgin and formed his own Big Honcho Media. His hearing-conservation film Listen Smart won the CINE Golden Eagle Award, and he has written songs with Dion DiMucci and Felix Cavaliere.

© 2025 Dan Beck. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

From Variety US