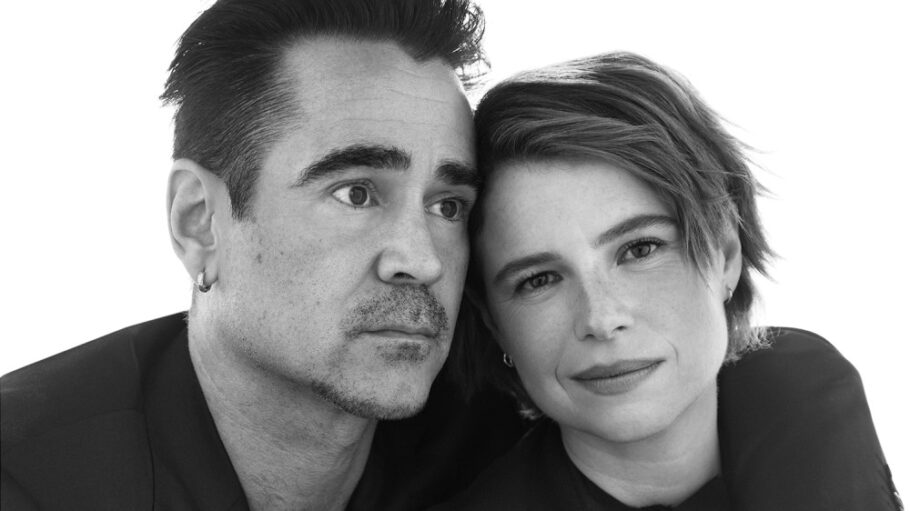

Colin Farrell and Jessie Buckley don’t know one another well when they sit down together — but almost instantly they go deep. It stands to reason: The two Irish actors both play challenging, emotional leading roles in literary adaptations this year. In Farrell’s case, Edward Berger’s “Ballad of a Small Player” has him acting the part of an addict in Macau, out of money and falling for a credit broker played by Fala Chen. For Buckley, Chloé Zhao’s “Hamnet” provides a moving, draining catharsis; she plays Agnes Shakespeare, an imagined version of William’s wife in the aftermath of the death of her son. Agnes is horrified, and then moved, to see that her husband has taken inspiration from their loss to write his greatest work — a testament to what Farrell and Buckley both know is the power of art.

Colin Farrell: I started watching “Hamnet” at about one in the morning. I ended at three a.m., and I was astonished. I was like, “Oh, jeez, do I have to see her now? Do I have to sit in front of her and talk to her?” Is it intimidation? It’s awe at what you went through.

Anyone who watches this can go, “Eh, what you went through, actors’ nonsense,” which I get. But the dignified perspective of a pain that I don’t understand … I’ve imagined, as any parent does, what is the worst thing that could happen to you? The dignity with which that pain is explored — I just didn’t think the film could turn around as extraordinarily as it does.

Jessie Buckley: Isn’t that what stories are? They allow those bits that are too hard to hold by ourselves to come through. The same with yours — the race of addiction and ego and trying to run from a life. Was there catharsis in doing that?

Farrell: I was wrecked by the end of it.

Buckley: But isn’t that a great feeling?

Farrell: Yeah.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

Buckley: When people say, “Was it hard?” I’m like, “Are you joking?”

Farrell: But it’s a beautiful difficulty.

Buckley: Like you’re trying to touch the edges of whatever the deepest truth is meant to be — and you’re really just touching the edges. I think it’s hard when you feel blocked or when you’re on your own. But when you’re in a community where the valve of creating something is so open — I never feel more awake.

Farrell: It is inevitably a communal experience. In doing what we’re lucky enough to do, you get to work with a community of filmmakers in front of and behind the camera, and you get to share all the uncertainties and the curiosities and whatever love or lack of love you may have felt in your life. You get to bring it to work. It’s a really beautiful thing.

Buckley: What was the first theater or film you saw that you were like, I don’t know what this is, but I can almost touch the mystery of it — and I want to peek in behind that door.

Farrell: I remember I was horrified seeing “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” I was raised on Steven Spielberg films and John Williams raised me through his scores — but in that film, and in a lot of his films, there was a central dysfunction of family dynamics. There’s all this exciting sci-fi stuff, but there was the Richard Dreyfuss character: There was a certain aggression and a certain inevitable disassociation that came between him and his family.

I remember being shocked by that as a kid. I was there to be entertained, and I was entertained. But there was also something very painful and very truthful at the center of this big Steven Spielberg film about aliens. That was the first time I remember seeing elements of my own family life represented on the screen. It didn’t have any definitive answers, but it was just this thing of feeling less alone.

Buckley: We didn’t have a TV until I was a teenager. Telling stories is so part of an Irish identity in so many ways. I went to my local town hall when I was about seven for an amateur dramatic production of “Jesus Christ Superstar.” I was so sure that a man had been crucified in front of my eyes; I was bereft. My mom had to bring me backstage to meet the actor. All of a sudden, both realities were true. It was true that he had died in front of me; but it was also true that he was just somebody who’d waved a magic wand. That effect is what’s mysterious. Which I guess is at the end of “Hamnet.” She’s so outraged that he has stolen something so personal of hers. And he’s created this portal for something that she can’t process by herself.

Farrell: And to give the community to present itself as more loving. Everyone else has given permission to reach out to Hamlet with a gesture of love and support. That’s the bit that kind of broke me in half as well. To just observe and be present in the company of grief and sorrow.

Buckley: You see how dangerous it is to feel. Your film, I can’t even imagine how much you must have sweated. When you meet [Fala Chen’s character], you can just feel, like “Oh my God, I can touch something so real. It’s so scary.” How scary it is to feel, and how much we run as fast as we can from it.

Farrell: The permission to be overwhelmed is a huge thing to give to each other, to give to our kids. I’m so fucking aware of the amount of privilege that I’ve experienced in my life and what rare air I fly in regarding what I do for a living. But at the end of the fucking day, there’s nothing I can do in acting that can make James, my oldest boy, talk or have language. [Farrell’s son James has Angelman syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that causes physical and learning disabilities.] Regardless of the facade, regardless of how the life seems to be — it’s a mess.

Buckley: It’s chaos. But that’s our job—

Farrell: To be in the mess. To lean into the mystery.

Buckley: The more I do this, the more I realize the job is to become more human. Take your hands off the steering wheel. How do you…

Farrell: Drive hands-free? Foot on the gas.

Buckley: Waymo.

Farrell: Every time I see one of those — oh my God. Well done, humans! There’ll be 50,000 drivers unemployed within the next two years. Well done.

Buckley: How do you travel to be unconscious like that and become more human and more scared? Maybe it’s not fear. But why did you want to do “Ballad”?

Farrell: I have mad moments of joy in my life and joy in work and joy with my kids. But I’ve always felt that the common denominator in regard to experience as humans is pain. The one thing we’ve all felt, really, is pain. I put fear and uncertainty under that banner. Not everyone, sadly, has felt joy. And that’s a great tragedy. But I’m fascinated with pain. Every single act of aggression or violence has its root in pain that has become personalized.

When I read “Ballad,” it was a character that .. there was no reason, no backstory given in the script — he just was somebody who was drowning beneath this agitated pain. I couldn’t really figure it out when I read it. I concocted whatever fiction for myself in regard to backstory. But I just wanted to explore it. I’ve had a history of addiction and bits of depression and anxiety — the whole smorgasbord of human frailties as well. Inevitably, you’re always drawing from your own personal experience, but I didn’t feel like I was drawing from the experience I had with addiction, which was very particular.

Buckley: Mm-hm.

Farrell: The addiction is just a consequence of certain things unanswered or certain uncertainties that are too fearful to even comprehend. So you pretend they’re not there. And you pretend that you have answers when you don’t have any business having an answer at that particular point. You just have to sit in the uncertainty of it all — sit with the agitation and the sorrow and the fear of that.

Buckley: It must have been amazing to shoot in Macau. It’s a kind of fantasyland. Your character, at one point, says, “I can be invisible here. I can create anything of myself.” How exciting, to be able to re-create yourself.

Farrell: That’s just a part of the fucking major excitement about what we do. I’ve experienced my own discomfort with saying there’s worth to what I do. OK, not as much worth as there is with a brain surgeon. I get it. But it’s really important as human beings that we share stories, because we can’t share very often in a peaceful way. Let us create this drama together and we can sit in a bipartisan way that is beyond ideologies and beyond politics in a dark room together and have an emotional experience. We don’t have to talk about it.

Buckley: Totally! I’ve found an education and discovered something that I didn’t recognize or see when I was younger through the stories that I’ve been lucky enough to play.

Farrell: Me too.

Buckley: And the women that I’ve been lucky enough to play — I never want to let any of them go. There’s no letting go of a character for me. I’m like, “You can stay right here.” All of the textures of what they are have woken me up to myself and the world.

Farrell: How did you survive this one? Her journey is all of these full lives that are expressed — how the hell did you survive it? Does it come home with you at night?

Buckley: I think it did. I try, whenever I step into a world, to say, “OK. I’m just going to be in this river for six weeks.” I met Chloé before I read the book, and then I read the book and there was something about this woman that… I was just so ready to meet her. I always have to have a level of unknowability; to touch that grief, I was like, “I don’t know where to go.” Where do you even begin with that?

I had just come back from filming “The Bride!” in New York and I was cracked wide open — broken. Chloé just wants you to be as present as you possibly can. She’s like that too. She wants the whole crew to be present. You’re all just stepping into the most potent essence in each scene. And what happens within it is none of your business. A lot of this stuff, I didn’t know where it was going to take me.

Farrell: You didn’t rehearse much?

Buckley: We hardly spoke. We started being very conscious of her dreams, and they became tools for me to fever-dream around the scenes in some way.

Farrell: So alive to every moment.

Buckley: In the bits around Hamnet’s death, I knew I had to go to a place…. Sometimes I find it hard to do the day: get in the car, come home and be like, “How is the weather today?” I knew for those two weeks, I needed to stay around that material. I said to my husband, “I’m going to book somewhere near the studio and just stay here for two weeks. I need to give it its commitment.”

Farrell: To be beneath that cloud for a while.

Buckley: Out of respect for what it must be like for a parent to lose a child. I always want to come in with the lightest of touches in everything I do. Chloé’s like that as well. If something doesn’t serve a moment, she just lets it go.

Did you have that experience with Terrence Malick?

Farrell: It reminded me a lot of “The New World.”

Buckley: Which is such a beautiful film!

Farrell: It reminded me of that visually. And also to be at the center of this experience of love and to want to capture it like a bird in your hand and make sure that it’s never lost to you again. But that’s impossible.

Buckley: What was it like making it?

Farrell: It was extraordinary. It was so alive. We shot it in continuity. There was a script that was 60 pages or 100 pages. There was a sense of discovery of this beautiful Eden that America is by virtue of the bounty of its land.

I loved working with Terrence. He was very curious himself. It’s lovely to be with the director who knows what they want to do. You can also feel from them that they’re willing to be as lost in the waters of uncertainty as you are. I wouldn’t be horrified if you told me Terry Malick was in Virginia picking up a couple of shots to put back in the film. Do you know what I mean? It feels like it still lives on. It’s a lovely feeling when you feel like the thing is never fully finished.

Buckley: I watched “The Penguin” the other day. You are extraordinary in that.

Farrell: Thanks, love.

Buckley: It’s so hard to work in a mask and see such humanity burst through that. I’ve never seen somebody so dexterous and so human in a mask. How did you do that?

Farrell: The last thing I want to say is that the mask allowed the real me to come out. But I certainly have felt ugliness in me. I can feel moments of envy or I can feel anger. It isn’t being born in the moment. It’s something from fucking seven generations ago. Because my face was covered, I was given permission — through being obscured, I was greenlit to experience a kind of revelation. When I saw the face, I started to feel a sense of sympathy.

Tell me about “The Bride!”

Buckley: From the moment I read it, it was like being plugged into an electric socket. I didn’t understand the energy of it. The space of what this character was that Maggie [Gyllenhaal] created — in the iconic iteration of “Frankenstein,” the bride has no voice. And Mary Shelley was a woman of dark need, dark love, immense lose.

Farrell: Dark instincts.

Buckley: Maggie was so uncompromising about — what is it to be monstrous? What is our capacity to be monsters as humans? In the vessel of a woman who’s born to be a mate, without any autonomy — what might she want to say about that? It was the biggest canvas I’ve ever played in. It was really intense. It was the wildest, most invigorating… I just felt an earthquake in me, and two weeks later went into “Hamnet” with bleached eyebrows, bleached hair, bleached everything.

Farrell: Oh God. I have no idea what to expect — and now I can’t wait to see it.

This is a conversation from Variety and CNN’s Actors on Actors. To watch the full video, go to CNN’s streaming platform now. Or check out Variety’s YouTube page at 3 p.m. ET today.

Production: Emily Ullrich; Agency: Nevermind Agency

From Variety US