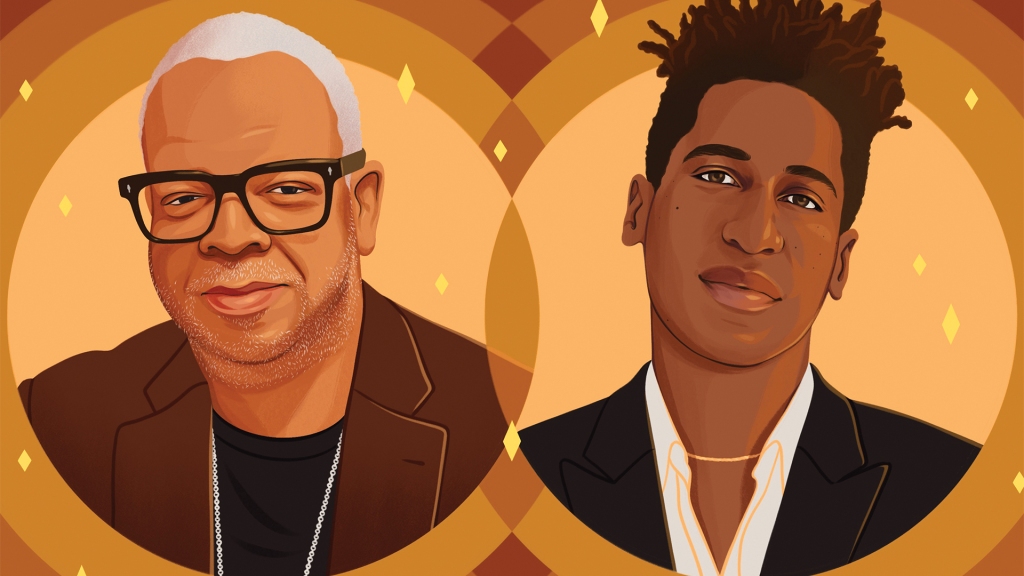

When the Grammy nominations were announced in November, the man who surprised everyone with the biggest stack — 11 — was Jon Batiste, known to TV audiences as Stephen Colbert’s musical director, and nominated this year for his wide-ranging album, “We Are,” and the soundtrack from Disney-Pixar’s “Soul.” His work in multiple genres makes him a kindred spirit as well as friend to composer-musician Terence Blanchard. Although Blanchard’s Grammy nominations come in jazz categories this year, his expansive vision made history when he became the first Black composer at the Metropolitan Opera, with his astounding work, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.”

The two join Variety for a conversation about awards, the folly of categorizing creativity and the healing power of music.

What does it mean to be recognized for the work you’ve done?

Batiste: I put my head down and work on the craft, and to have your peers recognize you, who understand what it’s like to do the same thing, is humbling. It takes a lot for us to do what we do, and the last two years, it’s been even more difficult. There have been so many things that we’ve lost that we can’t replace. And you realize the one thing that you do that can help people and to bring light into the world is still there. You can still create.

Blanchard: One of the things I think people don’t understand is that we’re not here to win Grammys. A lot of us are just trying to heal ourselves. The thing that I’ve grown to love about what it is that we do is that, in that process, you’re bringing so many other people along and helping them heal along the way. You’re putting yourselves out there, whether it’s the opera or doing an R&B album or scoring an animated feature.

You’re being recognized by people who do this and know the struggle. They know what it means, man, to put your life on the line because that’s basically what we’re doing. I think the average person doesn’t understand that when you dig in deep, and you’re trying to create something personal. It’s a scary thing to put it out there just for the entire world to possibly go, “Not for me.”

I firmly believe, when you’re honest about what it is that you do, it resonates with other people. I tell my students all the time, to learn their craft and be honest about what it is that they want to do and what it is that they want to say.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

George Floyd has had a huge impact on not just this country, but the world. You see what’s going on in Ukraine right now. These are human atrocities that have been affecting people along with the pandemic. People have been dealing with depression and anxiety in ways that they couldn’t have imagined. The one small thing that gives them a little bit of peace is the few notes and chords and rhythms that we put streaming on together to help take them away from the doldrums of this madness.

Have you seen a shift in your audiences as you shatter labels that have you pegged as jazz musicians?

Blanchard: This proves Duke Ellington’s point: There are only two kinds of music, good and bad. That whole thing of trying to put people in a box, I think, is gone. I hope it’s gone.

Growing up in New Orleans, I heard a lot of different things. I heard jazz, R&B, gospel, classical and opera. They resonated in my soul in various ways. So to be able to create all of these different genres, I don’t even think in those terms anymore. To me, it’s about really trying to make a statement, whether I’m playing with the E Collective, or whether I’m writing something for film, or an opera, or whether I’m doing something for a new project. The common denominator is a spirit that energizes music. That is the thing that I try to live for. When you saw Aretha Franklin fill in for Pavarotti singing “Nessun Dorma” at the Grammys, nobody cared that she wasn’t an opera singer. What we were thinking about was the spirit, the energy and the beauty that was being conveyed from her.

Not the musicians, it’s other people who are trying to create the labels. Musicians don’t create labels. It’s always people who write about us that create the labels or try to put us in a box. I don’t see myself in a box. I don’t want to see myself in a box. If you put me in a box, I’m gonna cut a little window on the door and I’m gonna crawl out of it.

Batiste: When we put labels on it, we just lie to ourselves and to each other. I remember when I listened to the first note of “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” I looked around the room; I was sitting next to Mark Ronson. Spike [Lee] was there. The range of people in the audience was not who you see in the Met. It’s impossible to look at that and not understand the historic significance of that. But also, from a philosophical point of view, it felt like another blow, another takedown of this false narrative of the genre that’s out there that has been marginalizing creatives, women and people of colofor so many centuries. To me, Terence is a hometown hero, a local legend, somebody who took over the world. We started with some of the same teachers. So it was like seeing an uncle or family member take over the world.

Blanchard: Opera is no different than some little young girls singing in church on Sunday. The only difference is one is done with orchestra and one is done in a church. But spiritually, and emotionally, they all come from the same place.

Music for many was therapeutic these last two years. Talk about getting your creative juices flowing and the struggles or challenges given all that was happening.

Batiste: The arts are communion. And that’s the amazing aspect of it that we can’t forget. We have to remember the power of what the arts can do when we team up with the media. We need to have coverage of what’s happening in the arts, not just because the arts is something that entertains people, but because the arts have a very, very important role to play.

Every day I follow what’s going on in Ukraine. You see these folks coming out and playing; there’s the girl in the bomb shelter playing “Let it Go” from “Frozen.” This is important to cover as well as strategy and political events and sanctions and all these aspects of things that are happening, because we can’t succumb to apathy and let our humanity be corroded by darkness. If we don’t see the full spectrum of what’s happening, we’re going to end up being completely overwhelmed by the darkness. That’s why I feel like it’s important. I’m so glad that we’re covering this in this conversation, and we talked about “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” and we were talking about the successes that we’ve had, not just because it uplifts us to work, but because people need to see what’s out there.

Blanchard: I don’t know if you remember when we were at the Oscars, but we were having a conversation. One of the things I remember telling you and Kris Bowers is that what’s more important is for us to be seen. We don’t know what young little kid is watching that thing and sees you grab an award or just sees us in the background wondering, who are those guys? When you go up to get your award, they know who you are, and you get a chance to speak, all of a sudden, you become a presence in other people’s lives.

I’ve known Jon since he was a kid. He is a testament to what I tell my students about all the time. I say, “If I’m doing this, you can be doing this.” You’ve got to let that spirit fuel your soul to create that. That’s because that’s the common denominator behind all of these different types of music that we’re talking about.

I was watching what’s happening in Ukraine and I realize, music doesn’t lie. You can sit down and you can talk about what’s happening or you can try to spin what’s going on, but those vibrations and those chords, those melodies, those things hit you because that doesn’t lie. It comes from a place of honesty, and no matter who plays it, I don’t care a great melody is a great melody. When you put that vibration back out into the world, that’s the thing that spreads positivity to a lot of people. It goes back to what you were talking about with us about the pandemic: music was necessary.

We all were struggling. To lose one of our teachers Ellis Marsalis and other musicians to this virus, creation was a necessary thing. The thing that I felt blessed about was having work to do. I was doing “Perry Mason” at the time, and “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.” Where we were in the world at that time, music, not politics helped heal a lot of souls.

From Variety US