It wouldn’t be “Scary Movie” without the Wayans brothers.

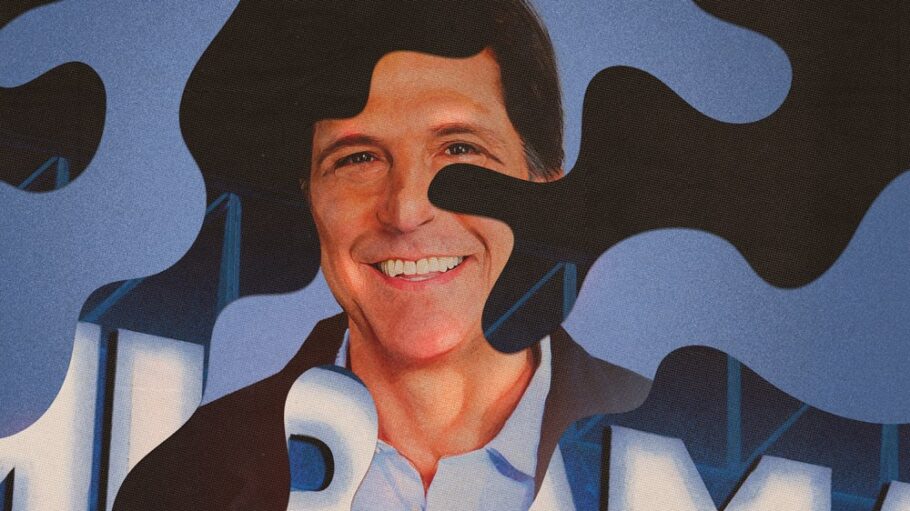

When Jonathan Glickman took over as head of Miramax a year ago, the studio was struggling to reboot the franchise. Glickman knew that a successful relaunch required one essential ingredient — the involvement of Marlon Wayans, Shawn Wayans and Keenen Ivory Wayans, the siblings who gave those popular comedies their subversive spark.

“You need to have some connective tissue with the original property,” Glickman says. “It gives legitimacy to a project so it doesn’t seem like just a cash grab.”

But getting the Wayanses wasn’t easy. The brothers believed that Harvey and Bob Weinstein, the bullying, bare-knuckle and (in the case of Harvey) disgraced founders of Miramax, had given them a “crappy” deal on the first film in the series, released in 2000, then “stole” their idea. By the time the third, fourth and fifth “Scary Movie” hit theaters, the Wayanses were no longer involved.

“It was so toxic,” Marlon Wayans says. “The way the Weinsteins handled the business of ‘Scary Movie,’ I could write a ‘Scary Movie’ about it. We probably should have sued.”

Before Glickman took the reins at Miramax, the studio was developing a reboot of “Scary Movie” independently from the Wayans brothers, though it did ask Marlon Wayans if he would shoot a cameo. He wasn’t interested. “The only way that I’m a part of it is if me and my family are delivering it, because this is our baby,” he says.

For his part, Glickman didn’t like the initial script, believing it lacked the right “flavor.” He asked to meet with the Wayans family to hear their pitch for the franchise’s future. He came away determined to make a deal. To sweeten the offer, he agreed to give the brothers more equity in the movies.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

“They needed to see that there’s an upside in terms of investing themselves emotionally and creatively in building this franchise,” Glickman says. “You want everybody rowing in the same direction.”

Getting the Wayanses back in the fold is part of the kinder, gentler, artist-friendly approach that Glickman is using to reinvent Miramax for the 21st century. That’s how he positions it when we meet at CinemaCon, an annual conference that brings together studios and movie theater executives in Las Vegas. We’re having lunch at Peter Luger, or at least the legendary New York steak house’s Sin City simulacrum. “It feels like sacrilege for this to not be in Brooklyn,” Glickman says as we are seated.

Pete Souza

Over a hamburger, Glickman lays out his vision for the studio. It’s one that involves investing in original movies and shows, along with dusting off decades-old properties from Miramax’s 700-title library of Oscar winners and genre fare. He’s been busy convincing the artists behind these films to be part of rebooting the properties that they so memorably worked on. Miramax is developing TV versions of “Cop Land” with the film’s director, James Mangold, as well as “Shall We Dance,” with Jennifer Lopez producing the series. There’s also a sequel to “The Faculty” that will be produced by Robert Rodriguez, the director of the original. In many cases, getting creative talent to return required smoothing feathers that were ruffled and settling feuds ignited during Miramax’s tumultuous Weinstein era.

It helps that the amiable Glickman, whose friends describe him as a mensch, is dramatically different from the volcanic Weinsteins. He thrives on collaboration; they feasted on combat.

“With Jon, you just know that his heart is in the right place,” says Derek Cianfrance, the director of “Roofman,” an upcoming Miramax release. “He’s got this energy and enthusiasm that makes it clear he loves movies. And he asks good questions that help you clarify what sort of movie you want to make. He doesn’t tell you what to do; he guides you.”

Glickman fell in love with movies at a drive-in in Wichita, Kan., when he was a child. Growing up, that’s where he first saw “Jaws,” “Alien” and other classics. “Movies were part of the DNA of my family,” Glickman remembers. “Culture was all around us.”

His father, Dan Glickman, was a congressman before becoming the secretary of agriculture and later the head of the Motion Picture Association of America, and his mother, Rhoda Yura, was involved in arts organizations. Instead of following his dad into politics, Glickman headed to Hollywood. As a graduate student at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, Glickman impressed his classmates with both his knowledge of film and his drive. Among those classmates were prolific screenwriting duo Al Gough and Miles Millar, who continue to work with Glickman on the Netflix series “Wednesday.”

“He’s always been a force of nature,” Gough says. “Somebody who’s always felt ahead of his time.”

“I’ve always considered myself a cinephile, but he definitely gave me a run for my money,” adds Millar, who fondly recalls editing Glickman’s stop-motion student film about a young man in dire financial straits whose credit cards spring to life. “There’s always been an intensity to John. It’s incredibly infectious and inspires creativity.”

That intensity was on display after Glickman attended a talk with Joe Roth at USC, followed the producer into an elevator to beg him to let him intern at his company, Caravan Productions, and landed his first gig.

“John August, the screenwriter, was a classmate and saw the whole thing,” Glickman says. “He told me it was the most psychotic thing he’d ever witnessed.”

From there, Glickman climbed the ladder, eventually becoming president of production at Caravan before moving to Spyglass Entertainment, the company behind “27 Dresses” and “Shanghai Noon.” When Spyglass’ leaders, Roger Birnbaum and Gary Barber, took control of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 2010, they brought Glickman over to pull the studio back from bankruptcy. He helped revive its fortunes, partly by implementing the same type of plan he is using at Miramax, going through the studio’s catalog to find older movies that could be reimagined. That led to successes such as an animated version of “The Addams Family” and “Creed,” Ryan Coogler’s blockbuster “Rocky” reboot. “It taught me that a catalog is really only valuable if it is being continually refreshed,” he says.

©Dimension Films/Courtesy Evere

Glickman left MGM in 2020 and launched his own production company, Panoramic. He wasn’t looking for another studio post, but the Miramax offer was too good to pass up.

“It’s a job that I was built to do,” Glickman says. “I’m a huge fan of film history, and Miramax’s library punches above its weight. It allows me to be satisfied creatively while appealing to my entrepreneurial side.”

Still, the job of studio chief has never been harder. In the 1990s and early aughts, Miramax brought an art-house edge to mainstream cinema, releasing critically acclaimed hits like “Pulp Fiction,” “Shakespeare in Love” and “Good Will Hunting.” Many of those films would struggle to get made today; they’re too unconventional, too brainy, too reliant on heart and humanity at a time when Hollywood is obsessed with movies about superheroes.

Glickman isn’t giving up on original stories, even though he knows they need to be made economically. He’d like Miramax to produce five to eight films annually, with more than half of them consisting of original material. If a movie isn’t part of an existing franchise, the goal is to keep budgets between $30 million and $50 million, to offset risk.

“Sometimes that means asking talent to give up some of their upfront salary while giving them a greater share of the upside in success,” Glickman says. “That makes them more invested, and the budget gets lower.”

Attracting the right star, preferably one firmly associated with a genre, is part of what Glickman believes helps lures crowds. To that end, he’s backing the action-thriller “4 Kids Walk Into a Bank,” because it features Liam Neeson, a stalwart of that time of film, or “Scandalous!,” a romantic drama with Sydney Sweeney, who recently scored with the rom-com “Anyone but You.” Colman Domingo, fresh off the Oscar-nominated “Sing Sing,” makes his directorial debut in the story of Sammy Davis Jr.’s love affair with Kim Novak. “People want a fun twist on something familiar,” Glickman says.

Glickman is also eager to keep developing new franchises for the studio. Miramax scored at the box office with “The Beekeeper,” a revenge thriller starring Jason Statham that made more than $160 million globally. A sequel is in the works with Statham hinting at “ambitious plans” to keep building out the series, while developing other films with the studio. “We’re already brainstorming new projects that have my creativity in overdrive,” he says.

But not every story works theatrically. So the studio is reconceiving some properties that originally were made for the big screen as streaming and TV programs or limited series. To that end, Miramax is developing shows or limited series based on “Gangs of New York,” “Chocolat” and “The English Patient,” all movies that were commercially and critically successful when they premiered more than 20 years ago. It’s also working on a show based on the more recent hit, “The Holdovers,” a boarding school drama that was an Oscar-winner when it opened in 2023. Glickman hopes that the film’s director Alexander Payne will be involved.

In other cases, Glickman is behaving counterintuitively by developing programming based on films that whiffed at the box offie. Despite their failure, Glickman believes they have regional appeal. That’s the situation with “The Shipping News,” a torpid 2001 drama about a journalist in Newfoundland, which could get a second life as a Canadian television series.

Getty Images

Miramax is still associated with Harvey Weinstein even though it’s been 20 years since the mogul and his brother ran the studio. They departed Miramax in 2005 over a deteriorating relationship with Disney, its parent company. From there, corporate ownership of Miramax changed several times, with Disney selling it to an investment group known as Filmyard Holdings in 2010, which then auctioned it off to BeIN Media Group, a Qatari-based entertainment company. Viacom became a part owner in 2019. Miramax’s corporate ownership could shift again, because Paramount Global, which Viacom was rebranded, is trying to get regulatory approval for its proposed merger with Skydance Media.

Glickman approaches the topic delicately. He starts by praising BeIN Media for its support and for encouraging Miramax to think of itself less as a domestic brand and more as a global player by connecting it with more international talent. As for Paramount Global, he says that Skydance Media, which has invested in franchises like “Mission: Impossible,” recognizes the value of a well-stocked film library.

“There’s a lot of opportunities if Skydance takes over, because they certainly see the world of IP the way that I see it,” Glickman says. “It’s sort of the foundation of their company. And I have great relationships there.”

Regardless of who currently owns Miramax, it was Weinstein who turned the studio into an indie powerhouse. And many of the accusations of sexual assault and harassment by dozens of women date back to his time at the company. After Weinstein’s fall in 2017, Miramax considered changing its name. It conducted surveys to see if consumers were put off by its association with the disgraced mogul, only to find that those viewers were able to distinguish between the company and its founder.

“I’m not clueless that there’s history there,” Glickman says. “But we don’t face any day-to-day business conversations where it’s a problem in terms of getting movies made or getting people to work with us. And the brand is still associated with those great movies that were made there. It represents a high quality of storytelling.”

Glickman hopes that Miramax continues to embrace creative risk-taking, even though he wants those artistic gambles to be fiscally prudent. As focused as he is on revitalizing the films and franchises that Miramax produced back when it dominated the indie landscape, he seems more excited about telling new stories.

“You can’t just remake a library; you have to replenish it as well,” he says. “That means zigging while others are zagging. Doing that is what leads to the big hits.”

From Variety US