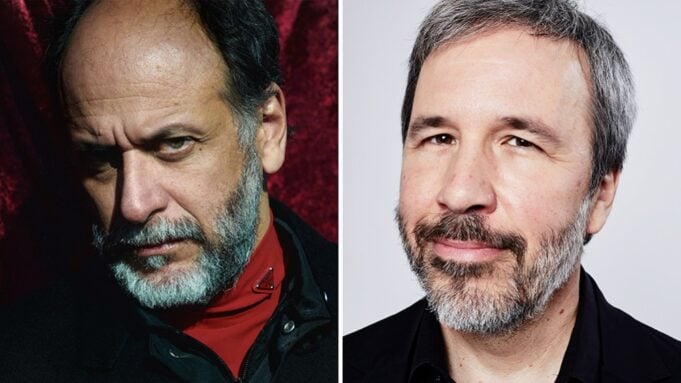

Denis Villeneuve and Luca Guadagnino have been linked for years by their shared taste in actors. After Villeneuve, 57, saw Timothée Chalamet in Guadagnino’s 2017 romance “Call Me by Your Name,” he cast him as Paul Atreides, the callow princeling turned desert messiah, in his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi novel “Dune.” And before Zendaya shot “Dune Part Two” she appeared in the 53-year-old Guadagnino’s erotically charged tennis drama “Challengers” as one side of a spiky love triangle with Josh O’Connor and Mike Faist. That film opened last spring, followed this fall by Guadagnino’s adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ feverish period romance “Queer” with Daniel Craig and Drew Starkey — his most complex and ambitious film to date, much as “Dune: Part Two” has been for Villeneuve. The directors, who know each other’s work intimately but have never really met, sit down in Los Angeles to discuss their appreciation for many of the same performers, as well as their different approaches to moviemaking.

Luca Guadagnino: We don’t know each other, but I hope we will become friends in time.

Denis Villeneuve: You’re sweet. I would love to.

Guadagnino: I feel there is something parallel between the two of us. We both are filmmakers who are working in English, but we’re foreign in the language. You are French Canadian, and I’m Italian. We both nurtured projects in our minds since we were kids. You notoriously read “Dune” at the age of 13 and you said, “I’m going to make it.” And I read “Queer” at the age of 17 and I said, “I’m going to make it.”

So when I heard that we were working with the same stars in the leading roles of our movies, I felt like, “Yeah. There is a companionship there.” I came to show “Challengers” to Z in Budapest, and while she was looking at the movie, I was walking in your sets [for “Dune: Part Two”]. It was a Sunday; it was empty. It was a great moment.

Villeneuve: I wish I had been there; I would have loved to walk with you. It would have been an honor for me. But I have to thank you because seeing Timothée’s performance in “Call Me by Your Name” is one of the main driving forces [for me] to think about Paul Atreides. There was something about that intelligence that I saw in his eyes and the maturity in that youth that you captured that I said, “Oh my God, maybe it could be him.”

Guadagnino: Do you agree with me that sometimes the movies we make are also a documentary on the actors?

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

Villeneuve: It’s true. When I started to work with him on “Dune: Part One,” I did feel very quickly that he was not used to a movie of that size. I mean, he was a young adult; his identity was not solidified. Outside the camera, I felt he needed to be protected and taken care of. When he came back on “Part Two,” he had worked with you again on [“Bones and All”], and I felt how he grew up between both. He was really a leading man. He was more assured; he knew his limits, how to focus. It was very moving for me to have that privilege to see him growing in front of the camera.

Now, about Zendaya. When I saw “Challengers,” I was, in a great way, destabilized and surprised — how she revealed another side of herself.

Niko Tavernise / Warner Bros. / Courtesy Everett Collection

Guadagnino: Yeah, she pulled a wonderful, almost Preston Sturges kind of sense of humor, like an old Hollywood classic cinema leading lady. Zendaya is not scared at all to play with the unlikability of the character, but then she conquers you completely.

Villeneuve: She’s very playful, but I was really happy and excited to watch her revealing a side that I have not seen. I don’t know if it does that to you when you look at your actors in other movies, that feeling of pride.

Guadagnino: Yeah, I’m very proud, like a dad. When you see that they command our gaze as audience, not anymore as directors, and they do so in these movies that are so entertaining — I’m so happy. It’s beautiful.

Villeneuve: Exactly, exactly, exactly.

Guadagnino: I remember I was in Venice and I went to see “Incendies.” A friend of mine was in the jury for first time directors, and the words spread on the Lido in three seconds that the movie was a masterpiece.

Villeneuve: You are very generous. I discovered your work through “Call Me By Your Name.” It’s still a movie that I’m thinking of very often, from the fantastic performances from the actors [to] the way you use the camera and the mise en scene.

Guadagnino: Thank you. I wanted to free myself from the obligations of the camera, so I decided to shoot it with only one lens. I picked 35mm — a limitation that freed us completely. Then I got back to the way in which I wanted to use the camera.

Villeneuve: I felt that freedom in the edit. Each shot is like a tableau, but sometime, there’s a shock between the tableaus that I thought was very propulsive and daring. You understand what I mean?

Guadagnino: I totally understand, but honestly, I have the same exact feeling watching your movies because I feel that what you build is an image that is juxtaposed [against] another image. And it’s the shock of the two images together that what makes your movie arresting.

Villeneuve: I think that if I wasn’t a director, I’d be an editor. I love editing. When I was doing documentaries, I took the most pleasure in the editing room, where you are limited to what you capture, and then create something new.

Guadagnino: In “Dune Part Two,” you do that beautifully and in a very experimental way. I think the third act is editorially very sophisticated in a way that moves through places and times and almost give the feeling of the Arrakis spice in watching it for me. That’s pure experimentation.

Villeneuve: I’m grateful that the studio allowed me to not stay in the, let’s say, more conventional zone of editing. That’s where I’m having the most fun.

When I watch your movies, you try to break the form or you try to push forward the language, but “Challengers” and “Queer” are so different. Are you trying to make a different movie every time?

Guadagnino: I think I do. I try to find a way to speak the different possibilities of the language of cinema that I learned watching great movies.

Villeneuve: “Challengers,” I was floored by the way it was shot. First of all, I absolutely believe that the three of them were pro tennis players. I don’t know how you achieved that. Do you storyboard a lot?

Amazon MGM Studios

Guadagnino: Usually, I never do storyboards. I don’t do even a shot list. I just go there with the actors and we block. Once we have an idea of what the blocking is, then I understand how to shoot it. But in “Challengers,” because I didn’t know anything about tennis, I had to go through a lot of planning. So I had tennis doubles for a couple of months with me, doing the points that were described in the script, repeating and repeating until I could understand what that meant first. Then I started to draw all the shots. Eventually, two, three weeks before shooting, we storyboarded all the tennis. I thought storyboarding meant a little bit of airless filmmaking. In fact, it was actually a good tool. If I hadn’t storyboarded, I would’ve died because the geometry of the court was too important not to [depict].

Villeneuve: It took me a while before finding, let’s say, my voice as a filmmaker. It took me a couple of movies. Some filmmakers, probably most of them, find their voice with their first feature. There’s a lot of people that are born with a very strong voice. Not me.

Guadagnino: Me neither, by the way.

Villeneuve: There were too many voices in my head, too many influences, too many directors.

Guadagnino: Did you want to try too many things, maybe?

Villeneuve: Yes, but also, I had watched maybe too many movies. With my fourth feature, “Incendies,” I finally felt that I was able to make shots that belonged to me. It was very still. There was not a lot of camera movement. I remember when I did “Blade Runner 2049,” Ridley Scott saying, “Your camera is really still. Should you do more movement?” Maybe he was right, but there’s something about stillness that really appeals to me deeply. It doesn’t mean that I don’t admire people that work, like you, with incredible camera movements, like in “Challengers.”

Guadagnino: I agree with you. The idea of movement for the sake of it is really insufferable in cinema. Because if everything can be done — you can flip the camera like this in every way — then nothing is real.

Villeneuve: We are both from the same generation. We were raised with cinema before computers. There’s something about the limitations that define the way we perceive movies. When I do visual effects, I use those limitations. I will not put a camera between the flying objects. I will keep a distance, like if it was real. But the young generation who are used to those crazy, absolutely free camera movements that are doing the impossible things that you’re talking about — I wonder if they will have the same references in their mind. You understand what I mean? I wonder if I’m a dinosaur.

Guadagnino: No, we are not. I am a bit grumpy, but I think they should go back to the great movies and learn. Today, I had the privilege of watching an amazing print of “La Grande Illusion,” Jean Renoir.

Villeneuve: Wow, wow, wow, wow.

Guadagnino: The way in which Renoir moves the camera, it’s dazzling! But always with a very specific purpose that is never about the kind of anxiety of boredom. It’s more about letting you understand.

Villeneuve: Meaning.

Guadagnino: Do you remember your first encounter with a coup de corps of cinema, like the first time you saw a movie that you felt like, “Oh, my God, that’s what I want to be”?

Villeneuve: I think it was on television, the beginning of “2001: A Space Odyssey.” At the time, on TV, the movies were shown once a year on a Thursday night at 8:00. I had to go to bed at 8:30 or something, and I was on the stairs cheating, my parents were thinking I was in my bed, but I was still looking at the TV. The opening really created a feeling of vertigo, to be in front of something that I was not understanding, something that felt totally real. To this day, it’s still one of my favorite movie because of that.

Guadagnino: It is beautiful, what you say, because I feel the connection with “Arrival” and “Dune” with “2001,” and then the sheer towering ambition of encompassing the universe into the screen that he was trying to go for.

Villeneuve: You were talking about Renoir, but this idea that the power of the language of the images — I’m not saying dialogue is bad, but for me, it’s something that should not be driving force of a film.

Guadagnino: I think dialogue can be interesting if it’s one of the elements. But if it becomes the driving force because you have to get the information through dialogue, we basically are bankrupt as filmmakers.

Villeneuve: Both “Dune” movies, my dream would’ve been to do those movies with as less dialogue as possible. There’s too much dialogue, personally.

Guadagnino: Do you think you can work on a movie of that scale and basically dismissing dialogue completely?

Villeneuve: Not completely. I would not like it to be like a…

Guadagnino: A gimmick.

Villeneuve: A gimmick, exactly. But as you said, it’s just something that is there as an element.

Guadagnino: Maybe it’s an element of behavior, more than an element of information.

Yannis Drakoulidis / A24 / Courtesy Everett Collection

Villeneuve: Yes, yes, exactly. I think you could watch “Queer” without dialogue, and you will absolutely understand what’s happening in the movie — the dilemma, the fear, the vulnerability, the anxiety, the loneliness. Don’t you think?

Guadagnino: That’s an amazing compliment. I hope so.

Villeneuve: I love the way you approach the vulnerability of humans. It’s very difficult to represent sexuality on-screen. You feel the realism of it; you feel the tension of it, the vulnerability. How do you approach it with your actors?

Guadagnino: The important thing is to let them feel completely free, not self-conscious. They shouldn’t think about their public image or any of that. Everything collapses in that moment of intimacy in a way that once it’s done, we also pinch ourselves and say, “Oh, we did it. How did you do that?” To get that intimacy, you have to make sure that they know that you are investing yourself into it completely.

Villeneuve: Because they have to trust you, absolutely. When you choreograph [the scene], how do you approach it?

Guadagnino: Usually, I use my wonderful friend, Fernanda Perez, who is the makeup artist of all my movies. I say “Fernanda, come here.” I can show them what we should do. Keep it light as well, make it fun and ridiculous. But then when you start rolling…

When we were doing “Call Me by Your Name” and Elio [Chalamet]has masturbated on the peach, then he is falling asleep, and then Oliver [Armie Hammer]shows up and it’s a bit salacious. Oliver eats the peach with the come. It seems to be another heightened moment of sex, then both of them confess to each other that they’re really desperate that summer is ending, and Elio starts to cry. We were in an attic in the villa where we were shooting. I was nearby because I’ve never been in the room when they shoot particularly intimate scenes. I don’t want to intrude. I describe everything, but then I go.

Villeneuve: Sorry. You describe…?

Guadagnino: And then I go. They have to make love with the camera.

Villeneuve: OK, OK, interesting, interesting, interesting.

Guadagnino: So when we cut, I moved into the room to say, “Thank you. That’s done, it was fun.” I look into the corner and there was Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, the director of photography, sobbing. He was really desperate because the summer of Elio and Oliver was coming to an end. That is the miracle of cinema, I would say, and the generosity of everyone involved.

Villeneuve: If I mention a title of a movie — if I say “M” from Fritz Lang — there’s an image that come in your mind spontaneously, that imprints somewhere in the back of your brain. When I think of “Queer,” the first image that come in my mind is Daniel Craig blowing that blood balloon.

Guadagnino: That’s an image that I pursued doing for 40 years.

Denis Villeneuve: It’s so powerful.

Guadagnino: It comes from my life because — I’ve almost never said the story. I was 10 years old. My father’s aunt was in another village far from Palermo. She was old, like 90. So we went to bring her with us home. The car was in front of the building and I was coming down the stairwell and I opened the door to the outside and I see this old lady blowing a big, red balloon, and I thought, “Wow, auntie’s blowing a balloon.” I’m transfixed by this image. The balloon becomes bigger and bigger and redder and redder until it pops and it collapses. She had a hemorrhagic [event] in front of me. So that image has been haunting me forever.

Villeneuve: When both men were making love and their hands were going under their skin, I thought it was so sensual and beautiful and nightmarish at the same time. Did you shoot them caressing themselves and then do the visual effects on top of that?

Guadagnino: The first thing was to invite these two incredible choreographers, Sol Léon and Paul Lightfoot, to choreograph that. They worked with Daniel and Drew for a couple of months before, which was a great way of breaking the ice, because they were in underwear rehearsing this thing forever.

Villeneuve: That’s brilliant. So they were used to the smell of each other. They were used to the proximity of the skin.

Guadagnino: Every time they were touching, we had to create the illusion that the hands were going inside [their bodies]. It was almost a year of work. That was a very long process, which I’m sure the same can be said of the incredible sequence of the arena of the Harkonnen [in “Dune: Part Two”], right?

Warner Bros. / Courtesy Everett Collection

Villeneuve: There was this idea to create another planet where the only manifestation from nature was the light. It’s an industrial planet, Giedi Prime, the Harkonnen [home world], and I came with this idea where the sunlight will kill the colors. If your own sun destroyed colors, politically it’s a very fascist world.

Guadagnino: Was it X-ray film stock?

Villeneuve: We shot with infrared cameras. I said to my cinematographer, Greig Fraser, “I would love to find an alien black and white. I would love to feel that it’s coming from another sun, from another reality. ” We experimented with different kind of black and white — film, digital, everything. It’s really infrared you see through the skin, you see the veins, the eyes become very sharp and dark like insects. But it’s very unpredictable. We had to redo all the costumes because we realized that, for instance, my [black] pants could be white and my shirt gray with infrared.

Guadagnino: So you had to create the costumes in the right color that fit the work?

Villeneuve: With the right fabrics, with the right textures to make sure that Feyd-Rautha [played by Austin Butler] would not look like a clown walking in the arena, that the Bene Gesserit sister will go from black to white.

Guadagnino: What is the part of the process that you are most like, “I wish it could be faster”?

Villeneuve: Honestly, writing. When you talk about the fact that “Queer” was written in a month and a half or something like that, I’m floored. I’m envious. It takes time to make the adaptation of both “Dunes.” I’m always struggling with the ambition of it and the limitation of budget and because those movies, people say, “Oh, those are big, huge.” But they are made from a fraction of the budget of a “Star Wars” movie.

Guadagnino: For what the movie is in terms of the story and the emotions, I’m very happy with what we had in our hands to work with, particularly the cast. I love my actors. Do you love your actors?

Villeneuve: I love my actors. There was no rest time between both movies, so when I started “Part Two,” I was already, honestly, tired. The thing that kept me alive through the shoot were the actors. I’m talking on a daily basis, waking up tired in the morning but going on set and being fired up, excited and finding my energy from the performances. I owe them everything.

Guadagnino: What are your ambitions for your filmmaking future?

Villeneuve: I would love to be able to bring something with less dialogue that is more cinematic.

Guadagnino: I feel that I’m very lucky to be able to do what I do. When I wake up and say, “OK, I can do another movie,” it’s like, what a privilege.

Villeneuve: It’s a privilege and it’s a responsibility too. Every time I finish a movie, I ask myself, “Should I go on? Is the flame still there?” I take the liberty to choose cinema after each movie and feeling deep inside me if I still have that fire. The day I don’t feel the fire, I stop.

Guadagnino: I am terrified of being in a place where I’m doing something and I don’t want to do it. So our task for the future will be to really understand when we don’t have the fire anymore.