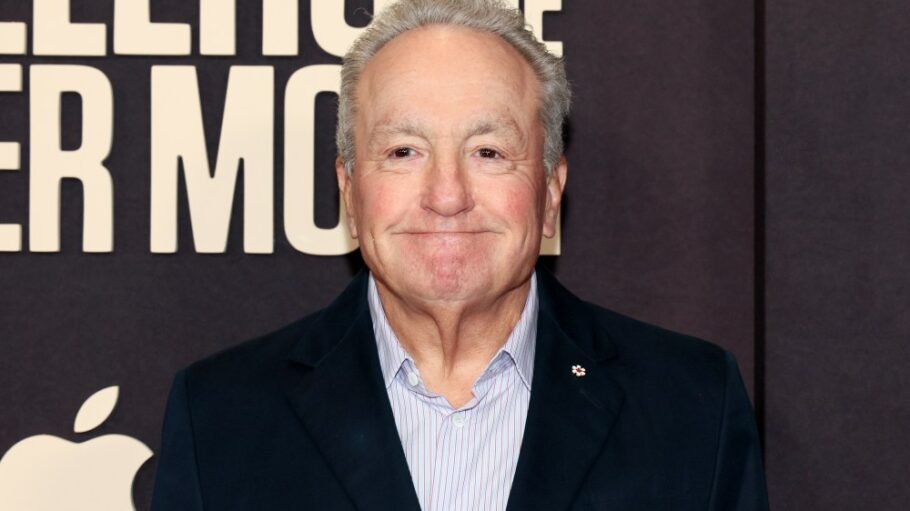

At the end of the Feb. 16 broadcast of “SNL50,” a tribute to the half-century reign of “Saturday Night Live” over American culture, Martin Short thanked executive producer and series creator Lorne Michaels, calling him “the man who made our dreams come true.”

Michaels — relentlessly parodied in popular culture, including on that very broadcast — seems at once familiar and remote. On film, his whimsical, dismissive mien provided the basis for Mike Myers’ “Austin Powers” villain Dr. Evil; on “SNL50,” his putative best friends from growing up in Canada (played by Vanessa Bayer and Fred Armisen) roasted him for his imperious management style when they helped him move. Onstage, at the end of a three-hour-plus special that would seem to have crystallized his sensibility, he was affable, but let others do the talking for him.

We have fifty years’ worth of evidence that such a role is most comfortable for him. The new biography “Lorne,” by the journalist Susan Morrison, reveals a surprising career ambition: After The New Yorker fired top editor William Shawn, Michaels provided him office space. He had harbored a desire to succeed Shawn himself.

The desire is surprising: Is Michaels a particularly gifted prose stylist? It’s not known. But then, is he, himself, a particularly funny person? Five decades into his sitting atop the heap of American comedy, and that detail isn’t quite known either. What has been the remarkably effective instrument of Michaels’ success has been his curatorial gift. A magazine editor — a good one, anyway — elevates sometimes discordant voices and brings them together under a unitary house style. Michaels, plucking from the Groundlings and Second City and, later, social media, has brought generations of comedians together in service of a broadcast that has alternately been described as ahead of its time, dated, nostalgic, and the very thing we need right now.

“SNL50” was all of those things, or none of them: It was a statement entirely about itself, a pleasurable and even delightful journey through years of American history in which “SNL” were the only referent. Like a talented editor, Michaels has always delighted in placing unexpected combinations of talent in conversation; Paul Simon, a stalwart of “SNL” since its inception and of American musical culture for still longer, duetted with 25-year-old pop star Sabrina Carpenter to open the show, for instance. Some of Michaels’ combinations worked better than others: The update of the recent sensation “Domingo” sketch, revised to now include past “SNL” stars Short and Molly Shannon, was charming, while Miley Cyrus’ and Brittany Howard’s performance of “Nothing Compares 2 U,” though well-executed, fell with a thud. The song was made famous by Sinead O’Connor, a performer “SNL” went out of its way to pillory after she went off-script and tore a photo of the Pope on air. If this was too unhappy to contemplate within the context of the broadcast, why play the song at all?

But then, Michaels’ sensibility, one that — through “SNL” and the shows its talent have gone on to make, including many feature films and TV shows from “The Office” to “30 Rock” — suffuses our culture, is one of walking up to a line and teasing the viewer’s curiosity, while not quite crossing it. Tom Hanks, on “SNL50,” presented a montage of characters from the past who, for reasons of sensitivity, the show could not depict today; there seemed a winking, giddy energy to the piece, as if the show were leaning in to tell a joke it knew couldn’t be repeated in polite company.

All of that is Michaels, a figure who is hard to know except through his work. Morrison’s biography paints a picture of a figure who is revered and feared by his subordinates; Bowen Yang and Andy Samberg’s digital short on “SNL50,” about the anxiety all the show’s staffers feel, seconded it. The fear is justified, perhaps: Michaels’ great feat was creating a melting pot where all the elements of our culture, over many years, simmer and emerge, lukewarm at times, as the curriculum one needs to consume to be prepared for the water-cooler or the algorithm. As TV, it’s of variable quality. But it’s a really good magazine.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

From Variety US