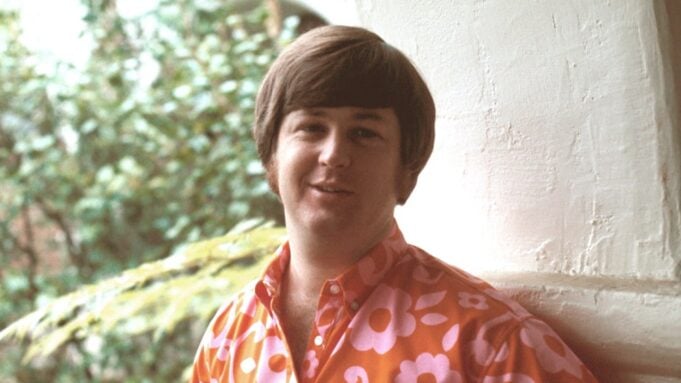

Brian Wilson, the brilliant musician who codified the California teen lifestyle in a series of ’60s hits by his band the Beach Boys, has died. He was 82.

In a post shared on Instagram, his family announced Wilson’s death. “We are heartbroken to announce that our beloved father Brian Wilson has passed away,” they wrote. “We are at a loss for words right now. Please respect our privacy at this time as our family is grieving. We realize that we are sharing our grief with the world.”

They signed off with the phrase “Love & Mercy,” which was the breakout single from WIlson’s first solo album and later the name given to a 2014 film dramatization of his life story.

Wilson had been active as a touring artist up through 2022. In early 2024, it was announced that he was suffering from dementia, and a conservatorship was established at that time for his immediate personal needs after the death of his wife, Melinda Ledbetter Wilson.

From 1962 to 1966, the Beach Boys racked up 10 top-10 hits and seven more top-40 chart entries for Capitol Records, most of them written or co-written and produced by Wilson; their popularity during this period was rivaled only by that of their English labelmates the Beatles, whom Wilson came to view as his artistic rivals.

A sensitive and ambitious talent, Wilson went on to push the boundaries of rock’s possibilities with a string of mid-’60s feats with his band: the lush and affecting 1966 song cycle “Pet Sounds,” the dazzling, complex 1966 single “Good Vibrations” and the long-mythical, tragically scrapped magnum opus “Smile.”

Encapsulating the group’s import in “The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll,” critic Jim Miller wrote, “In the ’60s, when they were at the height of their original popularity, the Beach Boys propagated their own variant on the American Dream, painting a dazzling picture of beaches, parties and endless summer, a paradise of escape into private as often as shared pleasures. Yet by the late ’60s, the band was articulating…a disenchantment with the suburban ethos, and a search for transcendence.”

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

While the Beach Boys’ close-harmony hits exemplified Southern California’s sun-blinded milieu, Wilson’s personal life descended into the kind of darkness worthy of a Raymond Chandler novel. The product of a torturous relationship with his father, Wilson from the early ’60s on experienced a series of mental breakdowns (which led to his early withdrawal from live performances with the group), struggles with drug and alcohol abuse, thickets of litigation, and deepening acrimony with his bandmates, who included two brothers and a cousin. In 1982 he was officially fired by his own group.

However, Wilson fought off his demons and opened a bright second chapter in the late ’80s, cutting a string of solo albums and receiving renewed acclaim via live performances of his masterpieces “Pet Sounds” and “Smile.” On the 50th anniversary of the Beach Boys’ founding, he took to the road again with the band after a decades-long absence.

With the other members of his group, Wilson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988 and the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2000.

He was born in the Los Angeles community of Inglewood; the family moved to the nearby city of Hawthorne when he was 2. His younger brothers Dennis and Carl were born in 1944 and 1946, respectively. Though largely deaf in his right ear from an early age, he was encouraged to sing and play by his father Murry, an amateur songwriter who controlled his sons with extreme emotional and sometimes physical abuse.

Guided by the example of the ’50s pop vocal group the Four Freshman and influenced by such doo-wop acts as Dion and the Belmonts, Wilson — who was fluent on the piano from an early age — schooled his younger brothers in close-harmony singing. During their years at Hawthorne High, he founded the band Carl & the Passions (so named to induce his brother’s participation) with his siblings and first cousin Mike Love. Al Jardine, a Wilson classmate at El Camino College, joined them in an embryonic group, provisionally named the Pendletons after the then-popular shirt.

In 1961, unbeknownst to his vacationing parents, Wilson and his bandmates cobbled together a few hundred dollars to record the demo of a new song written by Brian about surfboarding, a then-current craze that brother Dennis had embraced. Local entrepreneurs Hite and Dorinda Morgan recut the song, “Surfin’,” as a single on their Candix label, under the group handle the Beach Boys. Though it rose no higher than No. 75 nationally, the tune became a radio hit in Los Angeles, and gave the young band a commercial toehold.

In 1962, the Beach Boys were signed to Capitol Records on the strength of new demos, of the new surf anthem “Surfin’ Safari” and “409,” a drag racing opus co-written by Wilson and Gary Usher. The number became a two-sided hit, with its A side reaching the top 20, and it prefaced a long run of like-themed smashes.

The prolific act’s biggest hits of 1963-64 included a No. 1 pop single, “I Get Around,” and the top-10 45s “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” “Surfer Girl,” “Fun, Fun, Fun,” “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” and “Dance, Dance, Dance”; all of them were written or co-written and produced (at Western Recorders in Hollywood) by Wilson. Six of their albums reached the top 10, with the live set “Beach Boys Concert” hitting No. 1. Several lyrical Wilson compositions that became lesser hits or album tracks — “In My Room,” “Don’t Worry Baby,” “The Warmth of the Sun” — were harbingers of deeper writing to come.

During this period, Wilson also wrote and produced outside his group. He co-wrote Jan & Dean’s No. 1 1963 hit “Surf City.” More fatefully, he worked with a female vocal trio, the Honeys. He married 17-year-old group member Marilyn Rovell in December 1964; the couple would have two daughters, Carnie and Wendy, who themselves achieved huge chart success in the ’90s as members of the pop unit Wilson Phillips.

By the end of 1964, the Beach Boys were at the apex of their commercial eminence; they appeared in the pay-per-view concert film “The T.A.M.I. Show,” co-headlining with the Rolling Stones and James Brown. But, after a freakout on board a commercial flight from Los Angeles to Houston, the emotionally fragile Wilson announced that he would no longer perform live with the group, and would focus on writing and producing. Glen Campbell, then a top L.A. session musician, briefly replaced him on bass; he was succeeded in the lineup by Bruce Johnston, who became a long-term member of the band.

The hits continued in 1965 with the singles “Help Me, Rhonda” (No. 1), “California Girls” (No. 3) and “Barbara Ann” (No. 2), the latter drawn from the live-in-the-studio set “Beach Boys Party” (No. 6). The LP had followed a pair of increasingly ambitious albums, “The Beach Boys Today!” (No. 4) and “Summer Days (And Summer Nights)” (No. 2).

A song issued as Brian Wilson’s first solo single in early 1966 served as the bellwether of the album many view as the Beach Boys’ creative pinnacle. Though it fared no better than No. 32 on the charts, “Caroline No” was the first released effort from “Pet Sounds,” a powerfully affecting, intensely personal song cycle written with lyricist Tony Asher and meticulously crafted in the studio by Wilson and the same “Wrecking Crew” studio pros employed on many singles by his idol, producer Phil Spector.

Though the LP produced the hit singles “Sloop John B” (No. 3) and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” (No. 8), “Pet Sounds” was a comparative flop for the band upon its release in May 1966, peaking at No. 10. It bewildered many old fans, but it made an impact on members of the nascent rock press. In 1968, Crawdaddy editor Paul Williams wrote, “I decided ‘Pet Sounds’ was the best rock album yet with no advice from anyone and I never changed my mind.”

Both Paul McCartney and the Beatles’ producer George Martin subsequently acknowledged the influence of “Pet Sounds” on the Fab Four’s 1967 opus “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” Rolling Stone magazine would later rank the Beatles’ and the Beach Boys’ albums No. 1 and No. 2, respectively, in its 2003 roll of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

Disappointed but undeterred by the response to “Pet Sounds,” Wilson set to work on a single, co-written by Love, that reflected both his understanding of the cultural zeitgeist and his escalating use of psychedelic drugs like LSD. Seven months of sessions in four L.A. recording studios led to “Good Vibrations,” a rushing acid-tinged number decorated with ululating Theremin lines and throbbing strings. Unlike anything then current on top 40 radio, it climbed to No. 1 in late 1966.

Wilson viewed “Good Vibrations” as a component of the group’s next album, which he began writing in 1966 with musician and lyricist Van Dyke Parks. The impressionistic suite, described by Wilson to writer Jules Siegel as “a teenage symphony to God” and titled “Smile,” would encompass music from diverse cultures and styles ranging from rock to jazz and classical. As work on the record proceeded laboriously over the course of a year, its cryptic lyrics and decidedly non-pop orchestrations were greeted with increasing resistance from the other Beach Boys (especially the vocal Love) and skittish label executives.

Finally, amid a royalties lawsuit lodged by the Beach Boys against their label, the release of “Smile,” still deemed uncompleted, was cancelled in May 1967. The album immediately passed into legend, and became a much-bootlegged source of curiosity, wonder and debate. In Lewis Shiner’s 1993 science fiction novel “Glimpses,” the time-travelling protagonist returns to 1967 to help Wilson complete his masterwork.

“Heroes and Villains,” a dizzyingly constructed thematic centerpiece from “Smile,” became a No. 12 single in 1967; several of the suite’s tracks would be cannibalized for the Beach Boys’ albums “Smiley Smile” (1967) and “20/20” (1968), while the key composition “Surf’s Up” later became the title song on a 1971 album. But it appeared that the group had willfully stepped out of the musical vanguard of the day; they declined an offer to appear at 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival, which showcased many of the era’s most forward-looking acts acts.

No doubt defeated by the scuttling of “Smile” and the band’s internecine strife, Wilson saw his input as a writer and producer for the Beach Boys wane through the mid-’70s, and his behavior — which included showing up at public events clad in a bathrobe and slippers, grossly overweight and disoriented — became increasingly bizarre. He was still capable of contributing songs that became unquestionable highlights of such albums as “Sunflower” (1970) and “Surf’s Up.” But the No. 1 success of the Capitol hits package “Endless Summer” in 1974 seemed to mark the Beach Boys as an oldies act and a spent force.

In the early ’70s, Wilson busied himself with production and writing work on an album by American Spring, a group featuring two former members of the Honeys, his wife Marilyn and her sister Diane.

Alarmed by the decline in Wilson’s mental health, in 1975 his wife Marilyn enlisted the services of psychotherapist Eugene Landy. While Landy’s treatment would initially last only a year before his firing by Mike Love’s brother Stan, then the Beach Boys’ manager, his radical therapeutic approach appeared to stabilize Wilson’s behavior.

The final chapter in what would be Brian Wilson’s last full-time participation in the Beach Boys for nearly 40 years came in 1976-77, when he served as producer, songwriter, and vocalist on the albums “15 Big Ones” and “The Beach Boys Love You.”

Launched on a wave of hype that centered on the copy line “Brian Is Back,” the former album, released by Warner Bros. on the band’s Brother imprint, produced the group’s last top-five single for a dozen years, a cover of Chuck Berry’s “Rock and Roll Music.” (Ironically, Berry had legally claimed a piece of the band’s “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” the melody of which was lifted from “Sweet Little Sixteen.”) Though “15 Big Ones” was the band’s first top-10 album since “Pet Sounds,” both it and its successor were greeted with little praise from critics.

Disappointment and personal disarray awaited Wilson. In 1977, the Beach Boys declined to release “Adult/Child,” largely a solo project that featured big-band arrangements of several strong new compositions. Wife Marilyn finally divorced him in 1979. His participation in the Beach Boys, now signed to producer (and group manager) James William Guercio’s CBS-distributed Caribou imprint, dwindled again.

In November 1982 – 13 months before his brother Dennis’ drowning death while swimming in L.A.’s Marina del Rey – Brian Wilson was formally removed as a partner in the Beach Boys’ Brother Records operation, essentially fired from his own band. With his family’s complicity, he soon found himself back under the 24-hour-a-day care of Dr. Eugene Landy.

Landy maintained such tight control over Wilson’s life that it came as little surprise that Wilson’s first-ever, self-titled solo album, released by Sire Records in 1988, bore Landy’s songwriting credit (later expunged) on most of the tracks. Nonetheless, coming after a long drought, the record was embraced by some critics, who found merit in such songs as “Love and Mercy,” “Melt Away” and the expansive “Rio Grande.” However, a lushly produced follow-up, “Sweet Insanity,” repeated history by getting rejected by the label in 1990.

The same year, Wilson’s “autobiography,” “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” penned with Todd Gold, appeared, with glowing descriptions of Landy’s therapeutic wizardry. The book, which Wilson himself later disavowed, may have hastened a legal battle between Landy and Wilson’s family, including his brother Carl, over the musician’s conservatorship. In 1992, Landy was barred from practicing psychology in California, and legally separated forever from his long-term patient. (Carl Wilson succumbed to lung cancer in 1998; Landy died in 2006.)

In 1994, Mike Love sued Wilson and received $13 million tied to a latter-day court decision involving the 1969 sale of the Beach Boys’ publishing company Sea of Tunes. The pubbery was sold by Murry Wilson to A&M Records at the fire-sale price of $750,000. Wilson had successfully sued the law firm that represented Sea of Tunes in the sale for misrepresentation, and Love – whom Murry Wilson had not credited as a songwriter on more than 30 songs in the catalog — subsequently sued to claim his share of the award, winning $13 million.

In 1995, Wilson married his longtime girlfriend, former car saleswoman Melinda Ledbetter. The same year, he returned to the studio with Van Dyke Parks for the collaborative project “Orange Crate Art,” an opulently orchestrated suite of California-themed songs that failed to dent the album chart. He briefly returned to the Beach Boys fold for the independently released 1996 set “Stars and Stripes Vol. 1,” on which the group collaborated with contemporary country performers. A second solo album, “Imagination,” was released in 1998 by Giant Records, and peaked at No. 88.

The truest revival of Wilson’s career may have begun in 2000 when, backed by a band that included members of the young L.A. pop-rock band the Wondermints, he first performed “Pet Sounds” in its entirety onstage. He toured the album to great acclaim in the U.K. and the U.S. in 2002 and 2006, sometimes with the Beach Boys’ Al Jardine in tow.

In 2004, despite the presence of such celebrity guests as Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton and Elton John, Wilson’s third solo album “Getting’ in Over My Head” was overshadowed by his concert and studio reconstructions of “Smile.”

Following the concert debut of “Smile” at London’s Royal Festival Hall, the work was issued as an album, employing many of the same musicians who had backed Wilson on the “Pet Sounds” tours, by Nonesuch Records. It became his highest-charting solo release, climbing to No. 13 on the U.S. chart. Again, a widely admired U.S. concert tour followed; Beach Boys biographer and director David Leaf commemorated the event in a feature-length documentary. (In 2011, the boxed “Smile Sessions” set finally compiled the Beach Boys’ original recordings for the album.)

Wilson’s subsequent solo releases included “That Lucky Old Sun” (2008), a song cycle with narration by Van Dyke Parks; “Brian Wilson Reimagines Gershwin” (2010) and “In the Key of Disney” (2011), self-explanatory covers projects for Walt Disney Records; and the star-studded “No Pier Pressure” (2015), which marked a return to his original label home, Capitol Records.

However, Wilson’s highest-profile latter-day effort was probably “That’s Why God Made the Radio,” 2012’s full-fledged reunion with surviving members of the Beach Boys. Acting as producer, and co-writing 11 of the album’s 12 songs, Wilson was the key man in a regrouping with Love, Jardine, Johnston and David Marks, who had briefly stood in for Jardine in the early ’60s lineup.

The set rocketed to No. 3 — the Beach Boys’ highest U.S. album chart position since 1965 — and prefaced a short, wildly successful tour marking the group’s 50th anniversary. However, immediately upon the trek’s conclusion, Love – the frontman and leader of the band since the ’70s – tersely announced that Wilson would not appear with the Beach Boys at future concert dates.

Wilson’s tumultuous history was brought to the screen in Malcolm Leo’s 1985 telefilm “The Beach Boys: An American Band,” musician-producer Don Was’ 1995 documentary “Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times,” and Bill Pohlad’s 2014 drama “Love & Mercy,” in which the musician was portrayed by Paul Dano and John Cusack.

In January 2024, Melinda Ledbetter Wilson died, after she and her husband had been married for nearly three decades. The following month, two of his closest business associates, Jean Sievers and LeeAnn Hard, successfully petitioned — with support from Wilson’s family — to be named co-conservators of his personal and medical affairs, explaining that Brian suffered from dementia and Melinda had been solely responsible for his health care up until her death.

Wilson was still actively touring through most of his later years, including a 2019 headlining appearance at the Greek reviewed by Variety. It was understood by most fans that it took a village not just to recreate Wilson’s lushly arranged music but to allow him to feel comfortable on stage, and the shows were well-received by the Beach Boys faithful. His last tour took place in 2022.

He appeared only a few times in public after that tour ended. In early 2023, he sat alongside the other surviving members of his legendary band in the balcony at the Dolby Theater in Hollywood for the taping of “A Grammy Salute to the Beach Boys.” A 2024 documentary on Disney+, titled simply “The Beach Boys,” featured fresh footage of Wilson joining Mike Love, Al Jardine and Bruce Johnston for a friendly gathering on the beach, though only video and not audio of the reunion was included in the film.

Wilson is survived by daughters Carnie and Wendy and five adopted daughters from his second marriage, Daria, Delanie, Dakota, Dash and Dylan.

From Variety US