George Clooney has a cold.

Other A-listers would call in sick, but Clooney, who is on his second round of steroids, is powering through. “My body isn’t up for a fight like it was when I was younger,” he says.

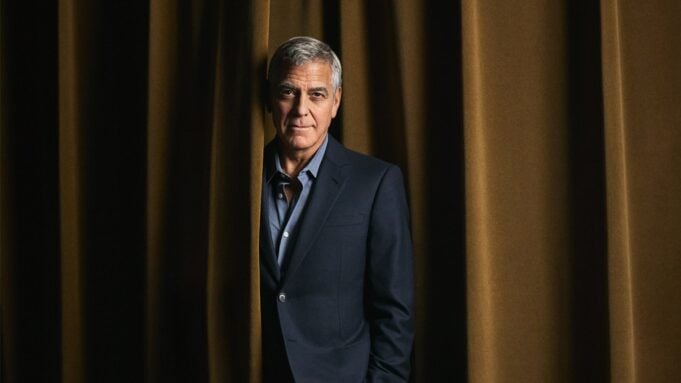

We’re sitting in an empty lounge at Ludlow House in downtown Manhattan to talk about his new movie, “Jay Kelly,” and the Oscar-winning star of “Michael Clayton,” “Up in the Air” and three “Ocean’s” films is sifting through a small fridge in search of sparkling water. His hair is mostly gray, his face slightly lined, but at 64, he’s still incandescently handsome in that effortless, Cary Grant-like way.

“My kids get sick with something; they’re fine in three days.” Clooney finds the water, pops it open and takes a swig. “I’m an old shit — it takes me forever!” He chuckles with that wry laugh we’ve heard for four decades. “I’d been traveling for work, and I got home and my son, Alexander” — who is 8 — “came running up to me saying, ‘Papa, Papa, I don’t feel well,’ and he sneezed in my mouth. I’ve been sick as a dog.”

Does that sound like a movie star to you? Clooney has been deeply enmeshed in the public consciousness for so long — since he became a phenom with “ER” in the ’90s — that he’s shaped our idea of celebrity as something not only glamorous, but good. He’s used his fame to draw attention to causes from Darfur to gun control while defending the role of a free press (he grew up the son of broadcast journalist Nick Clooney in Kentucky). At the same time, he’s become Hollywood’s eternal prankster, pulling one over on Brad Pitt, Matt Damon and his other big-name buddies with elaborate gags that make him more relatable.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

He was also committed to bachelorhood — that is, until he married human rights attorney Amal Alamuddin in 2014. Now a family man with two children, he’s ready for his next era, showing an industry obsessed with youth how to age gracefully on-screen. “If you’re trying to hold on to being a romantic leading man at my age, it gets sad,” Clooney says. “I don’t want to be pathetic.”

Unlike his other big-screen contemporaries, you won’t find him clinging to the side of a plane or romancing starlets long after he’s qualified for AARP membership. Instead, he’s stretching himself artistically. Clooney made his Broadway debut this year in a stage version of “Good Night, and Good Luck,” the 2005 film about journalist Edward R. Murrow he co-wrote, directed and appeared in. He followed that up by playing a movie star past his matinee idol prime in “Jay Kelly.” The complex character study pushed him in new directions as a performer, reigniting his creative spark and allowing him to dig deeper.

“I got my groove back as an actor,” Clooney says. “I rediscovered why I love this profession. It’s not that I wasn’t challenging myself on my last few films, but I knew how to play those parts.” He’s referring to “Ticket to Paradise,” which saw him in rom-com mode opposite Julia Roberts, and “Wolfs,” an action comedy about roguish fixers that reteamed him with Pitt. “With this one, I felt like I did when I started acting and was trying to figure it out,” Clooney says. “You’re thinking, ‘Am I a fraud? Am I going to be found out?’ It’s a really good place to be, to feel off your game.”

Clooney needn’t have worried. Not only did he score his best reviews in years, but he also earned a Golden Globe nomination for best actor in a musical or comedy and is in the thick of the Oscar race.

“Jay Kelly” is kicking off Clooney’s career pivot — even though, on paper, playing a movie star doesn’t sound like much of a stretch. But the A-lister he embodies in “Jay Kelly” is a self-absorbed, career-obsessed performer. He may be beloved by fans around the world, but he’s estranged from his family and doesn’t have any friends. When Jay accepts a lifetime achievement award in Tuscany, the only person who shows up is his long-suffering manager (Adam Sandler). Everyone else has other plans.

“When I watched it, I kept thinking, ‘Thank God George’s life is the complete opposite of this,” says Roberts, a friend and frequent co-star. “You’d be sending people away if there was a George Clooney tribute. The event would be standing room only.”

“Jay Kelly” follows its title character as he treks across Italy, flanked by publicists and stylists, trying to meet up with his daughter, who is backpacking through Europe. She resents him, as does the army of handlers he pays to airbrush his image. Clooney initially worried that Noah Baumbach, who co-wrote and directed the film, had the wrong idea about him.

“I read the script, and there was a part of me that went, ‘Does he think this is who I am?’” Clooney says. “Because I knew Noah a little bit, and this character’s deeply unhappy and kind of a jerk. But then I thought it might be fun to play someone who thinks he’s a good guy, but everything he touches, he destroys.”

As they worked on the film, Baumbach sprinkled more details from Clooney’s life into the script, enjoying the meta-ness of the story. Like Clooney, Jay is from Kentucky, and the film includes a moment where one of the actor’s fans urges him to run for president, pressure Clooney often receives from disaffected liberals.

“The illusion, of course, is that George is somehow playing his alter ego,” says Baumbach. “If George was playing a dentist, nobody would be asking about similarities. But because movie stars are reflections back at us, and we all have these histories with them, it feels more intense. They are kind of avatars for our hopes and dreams.”

Clooney, unlike his character, doesn’t stay cloistered in a celebrity bubble, untouchable and inaccessible. He acts like the mayor of any movie set, getting to know everyone by name and refusing to retreat to his trailer between scenes. “Jay Kelly” was no exception. Clooney and Sandler spent their downtime playing basketball, inviting everyone to shoot hoops with them.

“Anybody could walk up, and he’d throw them a ball,” Sandler says. “Because it’s Europe, where it’s more about football than basketball, George would show them the proper form and how to shoot. He turned about 20 Italian crew members into real hoops players.”

Clooney fosters an easygoing work environment, partly so he can be loose when the cameras are ready to roll. “I grew up in the Spencer Tracy school,” he says, “which is, you know, come in, be prepared, know what your character wants in the scene. Then, when they say, ‘Cut and print,’ you get on with your life.”

Pulling pranks is all part of the Clooney package; it helps keep things light and shows he doesn’t take celebrity too seriously. Friends say he spends years finding ways to catch them by surprise.

“He’s very patient, which makes him lethal when it comes to pranks,” Steven Soderbergh says. “He had one teed up for [producer] Jerry Weintraub that was jaw-dropping that he never even used. He’d somehow gotten ahold of Jerry’s golf clubs, and [when Jerry was napping] he took some very compromising photographs of them arranged in a way that clubs should not be arranged. It would have been seismic.”

While making 2014’s “The Monuments Men,” Clooney had the wardrobe department take in the waist of Damon’s costumes by an eighth of an inch every day.

“I was in my early 40s at the time, and worried about going to seed,” Damon says. “He just delighted in messing with me. Long after that happened, I came home from making another movie and put on a suit that was too tight. My first thought was that George had gotten into my closet.”

In 1998, Clooney was shooting his final season of “ER” on the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank when he heard that Paul Newman was a few soundstages away working on “Message in a Bottle.” He grabbed a golf cart and set out to meet one of his idols. He found Newman sitting outside, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. At this point, “ER” was one of the most popular shows on TV, commanding roughly 30 million viewers an episode.

“I pulled up and I go, ‘Hey, Mr. Newman,’” Clooney recalls. “And he clearly had no clue who I was. But he was friendly and we started talking. People would drive by going, ‘George!’ ‘Hey, George!’ ‘Hey, man!’ Bit by bit, he figured out that I was well known in some way. And as I started to leave, he goes, ‘Don’t let them keep you inside.’”

It took Clooney a while to appreciate what Newman meant, but gradually his warning became clear. “What he was talking about was fame, and the tendency to surround yourself with managers and PR people who build these walls of security so that you don’t get caught doing something stupid,” Clooney says. “But what happens is you can divorce yourself from what’s really going on out there. You need people in your life that tell you the truth.”

He thinks the character Jay liked staying in a self-congratulatory cocoon, a predilection that was exacerbated by his early superstardom. “I feel like Jay Kelly got famous young, and I don’t know how young people handle fame,” Clooney says. “There’s too much attention on you. You believe too much about how great you are. Some actors can deal with it when they’re young — Timothée Chalamet seems to — but I don’t think I would have been one of those people.”

In contrast, Clooney spent years as a journeyman actor, shuffling through bit parts on “Roseanne” and “The Facts of Life.” (“I have probably the best mullet of all time” is Clooney’s assessment of his sitcom work.) It was his performance as a womanizing pediatrician on “ER” that made him a household name when the show premiered in 1994. By that point, Clooney was 33. “I’d failed a lot,” he says. “I’d been rejected a lot. And so I was better prepared for success.”

It helped that he knew how fleeting fame can be, having watched his aunt Rosemary Clooney go from chart-topping singer and actress to cautionary tale as she struggled with drugs and lost opportunities. “She did everything wrong — there was booze and pills. You name it,” he says. “I was a kid in Kentucky, but when I did get to know her, the career was long gone. She wasn’t the beautiful blond from ‘White Christmas’ — she was trying to sing in clubs and having a real bad time.”

Clooney has been called “the last movie star,” and it is true that he has a kind of elegance and charm that seems increasingly rare. But he doesn’t totally buy it. He thinks there’s a rising crop of actors who are ready to take up the mantle, rattling off the names of Chalamet and Glen Powell as younger performers who impress him. He also praises Zendaya, calling her “an exceptional talent.” But he does acknowledge that they’re inheriting a fractured entertainment landscape. He came of age in the monoculture — when hit shows like “ER” or movies like “Ocean’s Eleven” commanded the entire public’s attention. That all changed as TikTok and YouTube made it easier than ever for anyone to achieve their 15 minutes of fame.

“The thing where you put someone’s name above the title and you go see a movie because they’re in it has ended,” Clooney says. “And I’m part of the last generation of stars who were a beneficiary of a studio really investing in them. When I was on ‘ER,’ Bob Daly and Terry Semel, who were running Warner Bros. at the time, brought me in and gave me a five-picture deal. Because their company had produced my show, they wanted to be in business with me for the long haul.”

They also were patient with their investment. When Val Kilmer dropped out as Batman, Clooney was hired to wear the cape and cowl. He assumed the superhero movie would prove his bankability. Instead, when “Batman & Robin” came out in 1997, it was a campy disaster that nearly killed the franchise and Clooney’s movie career.

“It was a very painful suit, and you couldn’t move,” Clooney remembers. “I would be laying on a board, and Joel Schumacher would direct you with a giant speaker, and he would go, ‘OK, George, and here we go. And ready? Your parents are dead. You have nothing to live for. And — action!’ And then they’d just prop me up and I go, ‘I’m Batman,’ and they go, ‘And cut.’ And they drop me back down, and then they carry me out on the board.”

Clooney regained his stride with 1998’s “Out of Sight,” a romantic thriller in which he smoldered alongside Jennifer Lopez in a sexually charged game of cops and robbers. It also kicked off his long association with Soderbergh. Critics embraced the film, and the response taught Clooney something valuable about believing your own hype.

“I got destroyed for ‘Batman & Robin,’ and fair enough — I’m terrible and it’s a bad film,” he says. “The next film I do is ‘Out of Sight.’ It’s one of the best films I’ve ever been in. I’m good in it because it’s well written and has a great director and cast. I didn’t learn how to act any better in those six months between projects. I was protected by the talent around me.”

Going forward, Clooney made a point of surrounding himself with visionary filmmakers like Soderbergh, Alexander Payne (“The Descendants”) and the Coen brothers (“O Brother, Where Art Thou?”), who made challenging stories mostly aimed at adults. And he largely steered clear of franchises that offered mega-paydays but would have locked him to a certain genre or a signature part.

“Most of my successes were middle-of-the-road hits,” Clooney says. “And that’s lucky, because I was never typecast. I could do all kinds of things. I could do movies that were very serious, like ‘Michael Clayton,’ and then do something wild like ‘Burn After Reading.’ It meant that once I couldn’t kiss the girl anymore, I could still have a career.”

Long before he was famous, Clooney learned about morality from his father, with whom he remains close. Clooney’s dad’s career in journalism inspired him to be an engaged citizen and led to his interest in the story of “Good Night, and Good Luck,” a drama about how CBS News stood up to Joseph McCarthy. When the film was released, Clooney intended to draw parallels between Murrow and how the media was covering the lead-up to the Iraq War. Two decades later, with Donald Trump in office, it hits differently. When Clooney played Murrow last spring, CBS News was settling a frivolous lawsuit with Trump so that he’d approve the sale of its parent company, Paramount, to Skydance. That enraged Clooney, as did ABC News’ similar settlement with the president over a defamation claim.

“If CBS and ABC had challenged those lawsuits and said, ‘Go fuck yourself,’ we wouldn’t be where we are in the country,” Clooney says. “That’s simply the truth.”

He’s only grown more alarmed as David Ellison, Paramount’s new owner, has reshaped CBS News’ coverage in a more MAGA-friendly way by installing conservative commentator Bari Weiss as editor-in-chief. “Bari Weiss is dismantling CBS News as we speak,” Clooney says. “I’m worried about how we inform ourselves and how we’re going to discern reality without a functioning press.”

Clooney, who always seems to run cool, grows animated discussing how certain members of that profession have abandoned journalism’s mission to hold the powerful to account. It makes him think about something Murrow says in both the film and the play. “‘Let’s not confuse dissent with disloyalty,’” Clooney says. “I mean, what a beautiful, important statement about who we are at our best. But all too often we fall short.”

Peter Mountain/Netflix

Clooney has long been one of the entertainment industry’s most outspoken liberals, so it’s no surprise to hear that he believes President Trump’s behavior flies in the face of Murrow’s ideals. “It’s a very trying time,” Clooney says. “It can depress you or make you very angry. But you have to find the most positive way through it. You have to put your head down and keep moving forward because quitting isn’t an option.”

What is surprising, though, is that before Trump set the country on a MAGA course, Clooney and the reality-TV star were friendly. “I knew him very well,” Clooney says. “He used to call me a lot, and he tried to help me get into a hospital once to see a back surgeon. I’d see him out at clubs and at restaurants. He’s a big goofball. Well, he was. That all changed.”

In 2024, Clooney made a big political stir, not by criticizing Trump, but for a New York Times op-ed he wrote urging Joe Biden to drop out of the race following his debate meltdown. Many Democrats were relieved that someone was taking a stand that might save the country from Trump, but the Biden family has continued to criticize Clooney for being disloyal.

Soderbergh says, “I thought, ‘Holy shit.’ It’s classic George. He knows there are going to be so many people pissed at him, but if something is wrong, he’s going to speak out. Somebody had to say it.”

Clooney wants to model his next phase as an actor on Newman, who he considers the gold standard in how to transition to elder statesman status. Instead of clinging to his heartthrob past, Newman focused on enriching the parts he played as he got older.

“He went from performing love scenes in ‘Absence of Malice’ to doing shattering work — and looking his age — in ‘The Verdict,’” Clooney says. “And it was seamless.”

Next up for Clooney is “In Love,” a low-budget drama in which he will appear opposite Annette Bening as a man with Alzheimer’s. It’s indicative of the more personal projects he hopes to make.

“I’m not going to be doing a whole lot of major studio kinds of films,” Clooney says. “The films that I’m going to be working on for the most part are going to be smaller. If I’m going to go off and do something and be away from my kids, there has to be a real creative reason for it. Money isn’t an issue for me anymore.”

But there’s one franchise Clooney plans to revive — “Ocean’s Eleven.” Although instead of a nostalgia play, he wants to explore what it’s like to pull off a heist when you’re no longer young and spry. He was inspired by the movie “Going in Style,” a ’70s comedy about a group of aging criminals, and he’s enlisted Roberts, Damon, Pitt and Don Cheadle to return as an older, but wiser gang. They are scouting locations and hope to start shooting next October.

“There was something about the idea that we’re too old to do what we used to do, but we’re still smart enough to know how to get away with something, that just appeals to me,” Clooney says. “They’ve lost a step, and they need to find a way to work around their limitations.”

Personally, Clooney says he’s happier than ever. He has a large network of friends, and makes a point of planning boys’ trips and keeping in touch with people through chat groups. He and Damon are part of a Wordle network that Clooney has dubbed “Nerdle” because of its intricacy — they do three puzzles every day, add up the scores and the winner gets to choose the word they start with the next morning. “George is frustratingly good at it,” Damon says.

He also has loved having a family, brightening when he talks about becoming a dad to twins in his 50s.

“This chapter of George’s life fills me with so much joy,” Roberts says. “Amal is an absolute rock star. I could never conjure up a dream girl like this for George, and to watch him with his kids is so special.”

“Jay Kelly,” with its portrait of a stultifying form of celebrity, may be very different from the way that Clooney operates on and off screen. However, Clooney’s art and life do converge at the end of the film as Jay sits in a theater watching clips of his performances. The scenes Baumbach splices together are all drawn from Clooney’s films — there he is, saving the world in “The Peacemaker,” working all the angles as an operator in “Michael Clayton” and sipping a scotch while playing a smooth criminal in “Out of Sight.”

It’s impossible not to be moved by the sheer weight of the filmography, as well as to feel that the period of cinema he represents, one in which star power was the biggest special effect of all, is slipping away. “When we shot it, all I had told him was that I wanted to show him something,” Baumbach says. “He didn’t question it. He just remained open to what I was going to do.”

The take Baumbach ended up using, one in which Clooney’s eyes begin to well with emotion, was the first one he shot.

“When you’re young you’re desperately figuring out a way to cry,” Clooney says. “You’re pulling out nose hairs and pinching yourself. But the older you get, the faster the emotions bubble up. I have no trouble tearing up now.”

Some things do improve with age.

From Variety US