In his classic 1994 essay “How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart,” David Foster Wallace pondered why so many athlete memoirs — and tennis player memoirs in particular — fail to provide sports fans with what they really want to know. What does it feel like to fail in front of millions of people? How does a human being handle such intense pressure? What actually goes through one’s mind in those do-or-die moments where the difference between eternal glory and lifelong disappointment is one tiny miscalculation or half-second’s hesitation? Maybe, Wallace eventually concludes, the answer to that last question is “nothing much at all,” and “the real secret behind top athletes’ genius may be as esoteric and obvious and dull and profound as silence itself.”

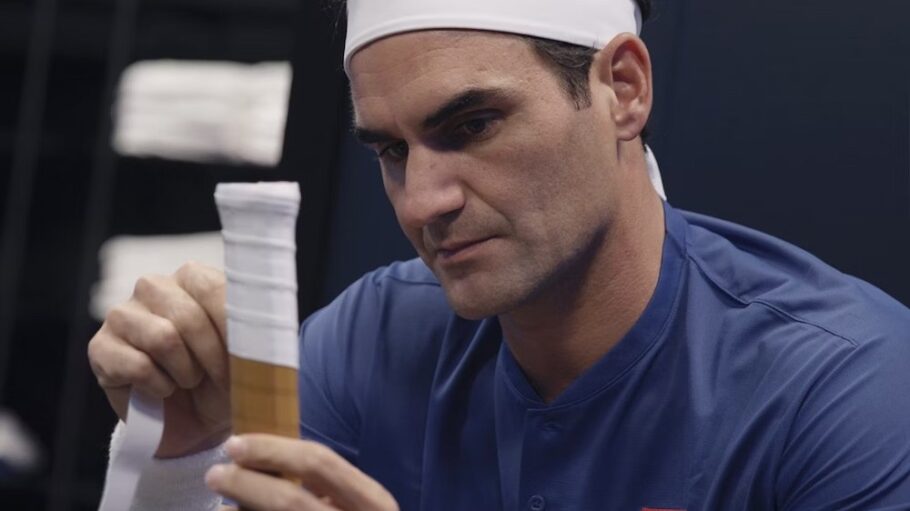

In his two previous sports documentaries, “Senna” and “Diego Maradona,” filmmaker Asif Kapadia has gone a great distance toward disproving Wallace’s thesis, using ingeniously edited archival footage to probe the psyches of Formula One champion Ayrton Senna and soccer god Maradona in all their noisy complexity. Directing alongside Joe Sabia, Kapadia attempts to crack a much tougher nut with the Prime Video documentary “Federer: Twelve Final Days,” a fly-on-the-wall snapshot of Swiss tennis legend Roger Federer during the short span between announcing his retirement and playing his final professional match in 2022.

For fans, this handsomely-mounted film’s level of access will be enticement enough, and its emotional peaks are undeniably stirring. But its limited scope and curious demureness prevent it from offering the full-scale portrait that a figure like Federer deserves.

Perhaps the biggest challenge here is that Kapadia’s aforementioned earlier subjects (as well as Amy Winehouse, subject of his Oscar-winning “Amy”) all possessed rather volcanic temperaments, equally prone to fits of self-destructive recklessness and flights of divine ecstasy while plying their trades. Federer’s genius, on the other hand, has always been of a more Apollonian variety. Arguably the greatest men’s tennis player ever, both his game and his public persona were defined by impeccable control, discipline and steady grace. And for better or worse, “Federer” largely follows his example.

As even-keeled, stately, respectful and, frankly, sometimes a tad boring as the film can be, Federer is a reasonably forthcoming subject, and less prone to bloodless sports clichés and diplomatic niceties than one might expect. He’s quite eloquent when discussing how, for elite athletes, dealing with retirement is sort of a test-run for confronting death, and his reflections on the injuries that brought his quarter-century career to an early close feel remarkably honest. For all his buttoned-down reputation, he makes for consistently intriguing company. It’s just that the circumstances surrounding him here don’t offer much in the way of conflict or urgency.

Proceeding chronologically through those final dozen days, “Federer” begins with a strangely long procedural glimpse of the tennis PR machine in full whirl, as Federer and his family record a farewell message announcing his retirement, then sweat over the details in the hours before it posts on social media. (Will the news leak? Will Federer forget to notify someone important beforehand? Why is Anna Wintour calling all of the sudden?) Once word is finally out, the focus shifts to preparations for Federer’s swan-song: a doubles match at the newly-minted Laver Cup tournament in London.

The tournament setting gives Kapadia and Sabia a natural way to introduce the major figures from Federer’s professional life, each of whom roll into London one-by-one and get a bit of “This Is Your Life” face time. Bjorn Borg, John McEnroe and the tournament’s namesake Rod Laver are all present to represent the old guard, but the real focus is on Federer’s trio of longtime rivals: low-key Brit Andy Murray, mischievous Serbian Novak Djokovic and Spanish great Rafael Nadal.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

While Federer clearly admires both Djokovic and Murray, it’s his relationship with Nadal that gives the film its most touching moments. First emerging as Federer’s potential young usurper, Nadal subsequently became his greatest rival, and eventually the pair developed what seems to be a genuinely deep friendship. They have a fascinating rapport — with Nadal the more openly emotional of the two — and display the uncanny sort of intimacy that can only be forged through years of head-to-head competition. “Tennis is not a contact sport,” Federer says while reminiscing on his matches against Nadal, “but we almost touch each other through the ball.”

Highlights from the climactic match — in which Federer is paired with Nadal, naturally, for a doubles contest against younger pros Frances Tiafoe and Jack Sock — are well staged, with the directors avoiding traditional broadcast angles and instead giving us an up-close, court-level view of the two aging greats in action. But the stakes here are undeniably low; were it not Federer’s final go-round, this match would barely have warranted a mention in his biography. More novel are the film’s glimpses at the mundane small moments that make up a tennis superstar’s day-to-day: the shop-talk in locker rooms, the endless shuttling between luxury hotel banquet halls and one hilarious debate between Federer and Djokovic over which dress shirts they’re supposed to be wearing for a photo shoot. (It’s comforting to learn that even Federer — who is usually the very model of Continental sophistication, and appears to be wearing a different Rolex in every scene — is still sometimes confused by the rules of formal menswear.)

Nonetheless, for all the film’s access, one is always aware of how much of Federer’s story remains untapped here. In one mid-film training session, Murray asks Federer how he’s holding up amidst all the hoopla, to which Federer gives him a knowing smile and says, “we’ll talk later.” Maybe someday Federer will let us into those conversations — until then, all we have is silence itself.

From Variety US