I’m worried that Sam Worthington is going to tear his skin off. He has this tic. When he gets nervous, his right hand snakes under his black T-shirt and starts to gnaw at his shoulder. And what’s got him scratching so intensely is an easy question: Who are the actors you look up to?

“It’s too hard to answer these questions, mate,” Worthington says in his thick Aussie accent.

What’s interesting is that over the course of a two-hour conversation in a hole-in-the-wall New York City diner, Worthington is an open book about his blown opportunities and personal struggles, recounting them in detail. Just don’t ask him about things like his “process” (a very un-Worthington word), because that’s when he’ll start to scratch.

Thirteen years ago, Worthington seemed to win the acting lottery, securing the starring role as a military grunt-turned-leader of an alien race in “Avatar,” James Cameron’s sci-fi epic — which earned a record-breaking $2.9 billion after it debuted in 2009. It was a role that almost every leading man wanted. Overnight it made Worthington one of the hottest stars in Hollywood. But that’s not where this story ends. Instead, the “Avatar” experience had a bruising coda, one in which Worthington, then 29, lost control of his life.

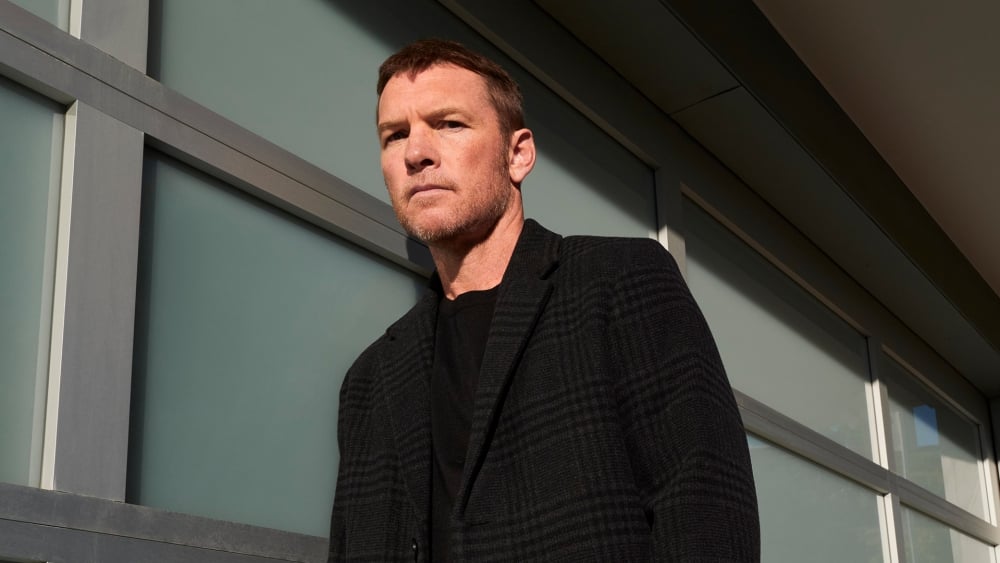

Greg Williams for Variety

This is a familiar tale in an industry where movie stars often discover that the fame and fortune they once so desperately sought comes at a terrible price. Worthington, now 46 and having nearly sacrificed everything to addiction, is telling his story of booze and self-loathing for the first time.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

He says that, following “Avatar,” he knew cities around the world not in terms of neighborhoods or monuments, but by favorite bars. Before a first-class flight, he’d down four or five glasses of Champagne while idling at the gate. His wife, Lara, told him she’d never seen anyone drink so much before the plane even took off. “I couldn’t see it,” Worthington says. “I thought it was normal.” He adds, “I didn’t like who I was. Drinking helped me get through the day.”

He would start drinking in the morning. “Nine out of 10 people couldn’t tell,” Worthington says. “They could probably smell it on me, but when they looked at me, they couldn’t tell. I was still doing my job — I just don’t think I was doing it very well.” Alcohol made Worthington erratic, jeopardized his career, and nearly ended his relationship. It could have cost him his life.

Now, eight years sober, Worthington is in a much better place as he prepares to once again endure a global promotional gantlet when “Avatar: The Way of Water” hits theaters on Dec. 16. The $350 million sequel is one of the biggest and riskiest bets in Hollywood — Cameron has indicated it needs to be “the third or fourth highest-grossing film in history” just to break even — and it arrives at a time when movie theaters are in a major slump. If the movie is as big a hit as box office analysts predict, it could revive their fortunes; if it fails, the future of cinema will look a lot darker.

Just as the first “Avatar” pushed beyond the boundaries of filmmaking to create something revolutionary, its sequel also hopes to mark a step forward in the medium. Filming took place over five years and required Worthington and his castmates to shoot many of their scenes underwater. And they weren’t just shooting the sequel — they were also filming parts of future installments in what Cameron ultimately hopes will mark a five-film saga of the Sully clan.

“The Way of Water” also marks Worthington’s return to the spotlight he’s avoided in recent years, as he’s concentrated primarily on smaller films like “The Shack” and supporting parts in miniseries like “Under the Banner of Heaven.” Today, he’s coming back to the world of blockbusters with a more complicated outlook on celebrity.

The Worthington who sits before me is handsome and slightly grizzled, with flecks of gray peppered throughout his short brown hair. He has the hint of a sunburn. In the 13 years between installments in the “Avatar” franchise, he got married and had three sons. Nearly everything, he says, revolves around them, even the decision to relocate from Australia to New York City, where stricter laws about paparazzi mean he can better protect his children’s privacy.

“Avatar: The Way of Water” mirrors some of the shifts in Worthington’s own life. Jake Sully, the improbable savior of a group of extraterrestrials known as the Na’vi, has also settled down and had children. That’s forced him, too, to grow up in important ways.

“There was a real synchronicity between Sam and the character,” says Cameron. “In the first film, Sam was playing a guy who would do anything and make any kind of fearless leap of faith. Well, a guy with kids does not make the same decisions. He’s not the kind of mythic warrior that he was at the end of the first film.”

Greg Williams for Variety

Worthington is an avid surfer, and there’s a metaphor that he returns to frequently in our conversation: the wave. It’s a propulsive, dizzying phenomenon that sweeps you up, holds you aloft, but always threatens to topple you and leave you struggling in its wake. “You’re riding it and everything looks great and people are cheering, but the wave is going to crash,” he says. “That’s the nature of waves. Then you see the next guy behind you and the next guy behind him and you go, ‘Oh, shit, I get this now. I understand what this industry can do.’”

In the immediate aftermath of “Avatar,” Worthington found himself plucked from obscurity and anointed by Hollywood as the Next Big Thing. He was good-looking, magnetic and blessed with the kind of Down Under intensity that made previous Australian exports such as Mel Gibson and Russell Crowe so irresistible on-screen. So for a while, the wave carried Worthington, the son of a power plant worker, farther than he ever could have imagined.

Before landing “Avatar,” Worthington was a finalist for the role of James Bond in “Casino Royale.” He flew to London, was filmed in the tuxedo and was fussed over by Barbara Broccoli, the producer of the 007 franchise, who went to his hotel room before the screen test to personally cut his hair to match her vision of the super spy.

“I could play Bond as a killer, but I couldn’t get the debonair down for the life of me,” Worthington says. “The suit did not fit.”

Then, on the strength of “Avatar,” Worthington was cast as a cyborg in “Terminator Salvation” and was gifted with his own franchise, playing Perseus in the “Clash of the Titans” films. He was nearly tapped to play Green Lantern in the 2011 superhero movie, but his bluntness may have cost him the role.

“It didn’t make much sense to me — the suit comes out of his skin?” Worthington remembers asking impolitically. “And I was like, ‘He’s got this powerful ring that can create anything. Well, what can beat the ring?’ The answer was, ‘Nothing.’ I was like, ‘Well, something needs to beat it, or it won’t be very interesting.’”

Ryan Reynolds ended up getting that part.

But for a time, it seemed like Worthington was circling, attached to or cast in all the top projects. The movie business needed a leading man of a certain age who could believably deliver a punch, and Worthington, with the body of a brawler, was being shaped into the action star of the moment. Initially, he was content to be packaged that way, believing that’s what you needed to do to get ahead. “Back then I used to do a lot of reflecting and research into careers,” he admits. “I thought that’s how you did it. But I was just putting my head up my own butt. It wasn’t healthy. The job isn’t about trying to crack a formula. It isn’t an algorithm.”

What he found was that those action movies didn’t really require much acting. Their directors were consumed with getting the big effects shots right, and the scripts were often being rewritten on the fly. There wasn’t much time to get into Perseus’ backstory, for instance, which left Worthington feeling adrift on set.

“You can’t create a character if there’s nothing there,” Worthington says. “On the ‘Clash’ movies, that was the problem. You were getting new pages every day, and it’s too complicated. The movies that I did right after ‘Avatar’ were great big spectacles, but I should have been looking for movies that pried a little bit more into the human condition. I was boring myself with what I was doing. And if I’m boring myself, then I’m sure as hell going to be boring an audience.”

“Terminator Salvation” didn’t really move the needle on his career, but the first “Clash” movie was a big enough hit that it sparked a sequel, “Wrath of the Titans.” Unhappy with his work on the first movie, Worthington decided he’d shake things up on the second one. In the interim between installments, Perseus, a demigod offspring of Zeus who saved humanity from a mythological creature called the Kraken, has been widowed and is raising a son while living off the grid as a fisherman. So, Worthington reasoned, all that child-rearing and catching fish didn’t leave a lot of time for calisthenics. In order to depict his changed circumstances, Worthington grew a beard and steered clear of the gym. It was the wrong choice.

“I looked at it as Perseus was half a god and half a dad, and he had decided that he didn’t want the god part anymore,” Worthington says. “So I decided to develop a dad bod and that I wouldn’t care what I looked like. Of course, that’s antithetical to what a studio wants when they pay X amount of dollars to make a movie about a chiseled hero. My arrogance clashed with the studio and the director’s vision, and it turned into a horrible fight.”

Looking back, he admits he should have at least talked to the director first. “I could have handled things differently, instead of showing up on the first day with a big belly,” he says.

Part of the problem was that “Avatar,” despite its massive budget, had been such a collaborative experience. Cameron and his crew were pushing the limits of CGI wizardry, using performance-capture technology to transform their actors into a tribe of 10-foot blue creatures and surrounding them with lush, fantastical surroundings that could be achieved only with pixels. It was an expensive, potentially career-ending bet for everyone involved, but Worthington never felt like the whole thing was riding on his performance.

“I don’t want my actors to feel like they’re on some big expensive movie and it all sits on their shoulders,” Cameron says. “I’ve seen how that can put pressure on an actor, especially a young actor, and I try to insulate them from that.”

When Worthington was trying out for “Avatar” he had a light résumé, having only headlined some Australian films and appeared briefly in studio movies like “Hart’s War.” But he had an impulsiveness that proved important when it came to attracting Cameron’s attention. When he auditioned for “Avatar,” the project was so shrouded in secrecy that Worthington had no idea what the movie was about or who was directing it. He was told to read a scene featuring a character named Jake Sully who is arriving on a fictional planet, and that was about it. Frustrated by the whole process, Worthington didn’t read the lines as he was supposed to, instead choosing to spit his gum at the camera in a show of defiance.

Greg Williams for Variety

“I was just angry,” he remembers. “It was like, ‘You’re not telling me anything. This is a waste of time.’ Later, when they were like, ‘Jim Cameron wants to meet you, and this was for his movie,’ I was just like, ‘Oh shit, I’m going to get in trouble.’”

Instead, his bizarre response vaulted him into contention alongside much better-known actors. The fuck-you attitude that Cameron found so arresting propelled Worthington through a monthslong audition process.

It was a posture that extended to all parts of the actor’s life. Just before he went in to read for “Avatar,” Worthington had auctioned off all his possessions and moved out of his studio apartment. He’d outfitted his car, a hatchback, with a mattress and had lived on the road. “I sold everything I owned to my mates because I didn’t like who I was,” Worthington says. “I needed to get the heck out. I was living in Sydney, and every time I would go to the bar, people would recognize me. I was rebelling against that.”

Liberated and with few ties, Worthington threw himself into landing the role of Sully. He never complained when the studio flew him to Los Angeles for myriad auditions — hell, staying in a hotel with a per diem beat sleeping in the car. And he grew close to Cameron, who would man the camera as they worked out scenes. The director became convinced that Worthington could chart Sully’s evolution from brash grunt to inspiring rebel leader.

“It was a bit daunting because he had an accent like Crocodile Dundee,” Cameron says. “I saw a lot of actors, names you’d be quite impressed by. But Sam was the guy who made me want to follow him into battle. He was the guy who made me want to go into hell with him, and the other actors never quite pulled it off.”

Despite the studio’s reservations about handing the central role in a $237 million film to an unknown, Worthington got the part. But telling him the good news was challenging. “It took us several days to reach him because he was somewhere on a mountaintop without a phone,” says Jon Landau, the producer of “Avatar.” “That’s who Sam is.”

Filming “Avatar” was creatively fulfilling, but selling it to the world by sitting for endless interviews and walking down red carpets proved hard for Worthington.

“Nothing could have prepared us for the reception,” says Zoe Saldaña, Worthington’s co-star in the movie. “Shooting ‘Avatar’ was very personal and comfortable. The aftermath of releasing it was completely the opposite. It wasn’t an easy environment for Sam. I adore him, but Sam is better at work or on set than he is in real, public environments.”

As his stock in Hollywood rose, Worthington came to resent the loss of his privacy. He clashed with paparazzi, getting arrested in 2014 for punching a photographer, and recoiled from the glad-handing part of his newfound celebrity. “I’d go haywire over someone asking me for a photograph or taking a photograph of me,” Worthington says. “If someone approached me, my anxiety would go through the roof.”

In response, he drank even more heavily. Some of that impulse, he suggests, was cultural. “In Australia it’s ingrained in the society,” Worthington says. “We don’t necessarily talk about AA and things like that. You don’t recognize it’s an illness, and you don’t understand that some people are just wired differently.”

“Were you a mean drunk?” I ask. Worthington pauses for a moment, his eyes betraying a flicker of discomfort. “I was an emotional drunk,” he says. “I got more emotional and erratic the longer I drank. I don’t think I was mean, exactly, but I could be belligerent, petulant.”

Eventually, Lara Worthington had enough. She gave her husband an ultimatum. “You can do what you want, but I don’t need to be around this,” she told him. It was said with love, Worthington says, not anger or disappointment, and it pulled him back from the brink.

Since giving up alcohol, Worthington has also adopted a new attitude about the roles he chooses to take on. He’s no longer chasing major studio films just to be the generic leading man.

“If I can’t bring anything to it, I’m not going to go and be involved in it,” he says. “I don’t want to do that again. I don’t want to just be the action figure standing in the front. And that’s OK. It takes a lot to understand what you do want from this industry.”

That decision has led Worthington to do some of the most interesting work of his career — playing an Army captain in the World War II drama “Hacksaw Ridge,” appearing opposite Harvey Keitel as a low-rent writer in “Lansky,” and co-starring as a fundamentalist Mormon who murders his niece and sister-in-law in “Under the Banner of Heaven.” It was that final appearance, in which Worthington was able to inspire the viewer to feel empathy for a man whose feelings of dislocation and self-hatred make him do the unthinkable, that best tapped into his gifts and hinted at a fruitful second act.

Andrew Garfield, who appeared with Worthington in 2016’s “Hacksaw Ridge” and this year’s “Under the Banner of Heaven,” says he’s noticed a change in the actor. “I feel like his approach to the work is shifting,” he says. “He’s become looser and more experimental. Sam’s got this great quality where there’s a lot of depth there. There’s this still exterior and a lot going on inside.”

Worthington says he’s also learning to temper those roiling emotions on set and preserve them for the camera. “In my 30s, I was young and arrogant,” he says. “The older you get, the calmer you get. When I was young, I’d yell and be hotheaded and be adamant about my ideas. If you yield a bit and compromise and communicate, you find something that’s better than anything you’d come up with.”

It doesn’t mean that Worthington is saying no to Hollywood epics. In fact, some of his upcoming projects are among the most ambitious ever attempted by the movie business. He’s set to appear in the next four “Avatar” films, which are slated to come out between now and 2027. When not in Pandora, Worthington will co-star in Kevin Costner’s “Horizon,” a planned quartet of films that unfold in the West before and after the Civil War. The idea is to chart the development of one town throughout a turbulent period in American history. For Worthington, it was also a chance to work alongside someone who had endured and survived the white heat of celebrity. After all, few actors have achieved the level of fame that Costner did in the late 1980s and early ’90s.

“We never talked about it explicitly,” Costner says. “But I’m not surprised that Sam has mixed feelings about stardom. In this business, at first you don’t think you are ever going to work. Then you get your chance and find success, but what you find is that people don’t want to just talk to you about the movies. There’s a craving for people to know everything that they can about your politics, your marriage, your personal life.”

As the title suggests, large parts of the second “Avatar” take place underwater. In the film, a colonizing force has returned to Pandora, hoping to establish a new home because Earth is becoming uninhabitable. Jake is leading the resistance, and he and his wife, Neytiri (Saldaña), and their four children find themselves targeted by Stephen Lang’s Colonel Miles Quaritch. To protect their kids, the Sullys seek refuge with a clan called the Metkayina, who live along Pandora’s reefs and have adapted to life in the ocean.

All that swimming and diving presented an acting challenge for Worthington and his castmates, all of whom were taught to free dive. Kate Winslet, a new addition to the franchise, was able to hold her breath for seven minutes, Saldana managed five, and Worthington jokes he made it “15 seconds.”

“I thought, ‘This guy is a surfer. I’m sure he’s been held down in the washing machine and had to hold his breath for a minute until he could get out of turbulence,’” Cameron says. “And he said, ‘No, surfing is about staying above the water.’”

Shooting on “Avatar: The Way of Water” started in 2017, and much of filming took place in an enormous tank — 120 feet long, 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep — that was constructed in Manhattan Beach for the production. Cameron and his crew developed technology that would allow them to do performance-capture work underwater, and Worthington and his cast were encouraged to learn how to “act” in their surroundings. That meant, in Worthington’s case, not only figuring out ways to show rage, hurt, love and other emotions while swimming, but also engaging in an elaborate fight scene in the murky depths with Lang in which the two enemies attack each other with chokeholds.

“We were doing something that had never been done before,” Worthington says. “But Jim and I get along because I’m fearless. If he asks me to, I’m going to dive in. I’m good at putting aside all the mechanics and just focusing on ‘What does the boss need me to do?’”

There were other challenges. Worthington preferred to spend most of his time underwater, getting oxygen from a tank between takes, instead of surfacing after each shot. So what happened when nature called? “There’s a lot of stuff going on in that water that you don’t really discuss,” Worthington says. “You’re 30 foot down and you need to go, you go. You hope that the water doesn’t turn pink.”

Worthington says the whole experience of making “Avatar: The Way of Water” encapsulates everything he loves about moviemaking. Hawking the film, however, will require him to undergo a marathon of junkets, television appearances and premieres. It’s the kind of global rollout that he previously found so terrifying. This time, he’s hoping to approach it with a more laid-back attitude. He’s also eager to look out for the young cast, many of whom are still teenagers or just entering adulthood.

“I feel protective,” Worthington says. “I want these kids to know that if there’s any issues or questions, they shouldn’t be scared to reach out. I’m not going to offer advice if they don’t want it, but I can help them navigate what happens when stardom hits them.”

Our time together is ending, and Worthington, a regular at this particular greasy spoon, walks to the back of the restaurant to say goodbye to the waiter and hand him two $10 bills, a generous tip considering all he had was coffee. As we leave the diner, Worthington confesses he’s worried about an upcoming photo shoot. “I hate having my picture taken,” he says. “I spend most of my career trying to ignore the camera.”

With that, we part ways. Before I turn the corner, I steal one more glance at Worthington walking down 10th Avenue, navigating past a construction crew that’s tearing up a large part of a sidewalk and street. He’s hunched over slightly, his hands in his pockets, an anonymous figure in a city too big and buzzing to pay him much mind.

Styling: Jeanne Yang/The Wall Group; Coat: Mango; Sweater and pants: Hermes: Boots: Grenson

From Variety US