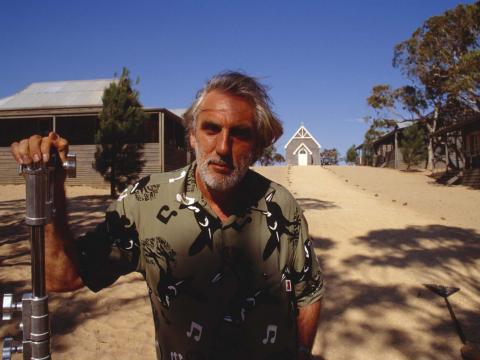

Australian director and Hollywood veteran Phillip Noyce had never imagined taking on “Rabbit-Proof Fence”.

At the time, Noyce was in high demand in Hollywood, having made the films “Patriot Games” and “Clear and Present Danger”, and also had the big budget 1999 film “The Bone Collector”, starring Denzel Washington and Angelina Jolie under his belt.

Paramount had signed Noyce on to make another film with Harrison Ford in the “Jack Ryan” series of films he had directed that began with “Patriot Games”. Noyce was about to start shooting on the film, when he was approached by the Australian writer behind “Rabbit-Proof Fence”, Christine Olsen, who first corresponded with Noyce in the middle of the night.

“I was preparing to shoot another “Jack Ryan” story in the series of films that I’ve done for Paramount with Harrison Ford and Christine Olsen, the writer of “Rabbit Proof Fence” who’d adapted the book, rang me in the middle of the night. She got the time difference between Sydney and Los Angeles completely wrong. And she woke me up at 2:30 in the morning and said that she had the perfect script for me, and I was the perfect director for that story. And she was a little nervous and she came across as quite crazy I thought”, Noyce muses.

While Noyce initially had little interest, this would change when Olsen managed to get the film to his assistant, and Noyce’s staff began urging him to look at the film.

“[My office just kept saying], ‘You’ve gotta read it’,” Noyce recalls.

Despite his reluctance, once Noyce read the film, based on Doris Pilkington Garimara’s book “Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence”, he knew he had to do it, and in doing so, turn down the Harrison Ford film.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

“[When I read it], I knew it was time for me to give up what I’ve been doing and to escape and follow the kangaroo on the side of the airplane back home,” Noyce says.

Determined to make the film, Noyce returned home to Australia.

“I came back to Australia, I thought, ‘Okay, if we don’t find the money, we’ll just shoot the film on my little Sony video camera’,” Noyce says with a chuckle.

Despite Noyce’s Hollywood success and track record, he faced fierce resistance from many in Australia, who told him he would not be able to make a film about the Indigenous experience.

“Everyone told me, you’ll never raise the money for this film ’cause Australians just will not go and see a film about Indigenous experience. There’s been films made, they’ve all failed and yours will fail too, so you won’t raise the money. And if you do raise the money, no one’s gonna go and see it anyway, so don’t bother,” Noyce recalls.

Having been familiarised with the mechanics of Hollywood, and their publicity machine, he realised the film would need a significant marketing campaign.

“Knowing what I did about how Hollywood worked, I thought, ‘Well, okay, [like Hollywood], the way around this is to make the Australian audience feel as though they can’t go on in their lives unless they see this movie’. So, that’s what we did,” he recalls.

Borrowing from the Hollywood playbook, Noyce brought on marketing consultant Emma Cooper, who was crucial to the international and local release, and would later become a producer of her own films (“Penguin Bloom”). Their first step was to hold an open casting call for the leads on the Channel 9 “Today” show.

“Emma arranged for me immediately to go onto the “Today” show, because I was back to try and find those three little kids. And so once again, going right back to the late ’30s in Hollywood, I took a leaf out of Hollywood’s book, which was to start a competition to find the leading ladies of my movie, and the “Today” show took up that challenge and appealed to Indigenous parents all over Australia to start sending in their clips of their kids, their home movies and photographs and everything,” Noyce recalls.

“Plus, they assigned a camera team with a young man called James Thomas directing it who followed us around the country, as we went by light plane, by Range Rover and boat and so on to all these settlements, particularly in Western Australia and the Northern Territory where contact had occurred much later than on the East Coast, looking for the three kids that would be in the film,” he adds.

Another crucial part of the film was its supporting roles, particularly the key part of AO Neville, ‘Chief Protector of Aborigines’, who removes the three girls, Molly, Gracie, and Daisy from their parents.

Noyce’s first approach for that role was to esteemed Irish actor, Kenneth Branagh, who said yes within 24 hours, despite a fee which was much less he would normally get.

“We sent his manager in Hollywood the script, and the next morning he wrote a note to me saying, ‘I’m in, I’m ready. My manager and agent will argue about the money, but don’t worry, I’m there’. That was overnight,” Noyce remembers.

“He wrote me about a seven page treatise on AO Neville explaining what he was going to do, which I agreed with. And as he said, ‘I’ll be there’. And he was,” Noyce continues.

“And he worked for little pay. Signing Kenneth on was the easiest casting experience of my whole life,” he adds with a laugh.

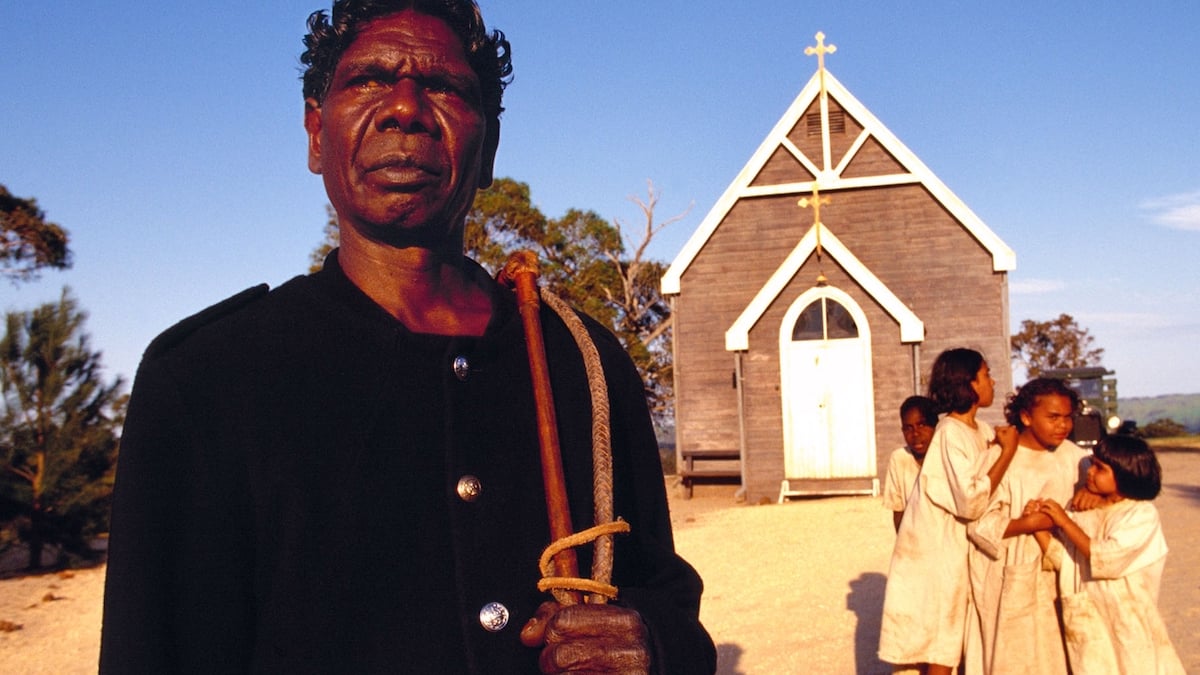

Making the film also gave Noyce the chance to work with two long-time friends, who were central to the film, actor David Gulpilil and cinematographer Christopher Doyle.

Playing one of the most important parts in the film, tracker Moodoo, the late Indigenous actor Gulpilil was a friend of Noyce’s dating back to the ’70s.

“In 1973, I was a student in the first year of the Australian Film and Television School (now AFTRS). And David was brought to the school to learn filmmaking. So, we became good friends and he stayed with me and my then wife, Jan Chapman, in our house in Allendale. So, I’d known him for many years, but we’d never worked together,”,Noyce recalls.

“David understood his character, of course, from his own experience. There will never be another one like him,” he adds.

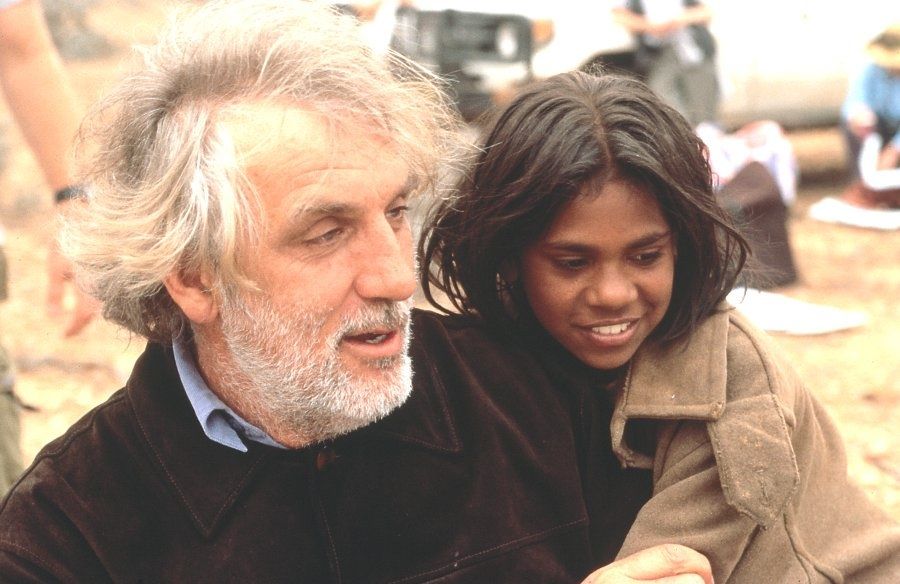

Gulpilil was also essential in guiding the actors making their debut as the leads of the film, Everlyn Sampi, Tianna Sansbury and Laura Monaghan.

“He immediately connected with Everlyn Sampi through dance, through gestures and through inspiration as a Indigenous storyteller who had played many characters and understood the power of cinema, he instilled in her a sense of the possibilities that could come from telling this story.”

CinematographerDoyle, who had gained international renown for his work with Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai, was another key component the film.

Noyce first met the cinematographer in the late ’70s as he was just starting out. The two remained friends and stayed in contact, and had wanted to team up for years.

Another integral element of “Rabbit-Proof Fence”, is the film’s score by legendary British singer, Peter Gabriel.

At the time of making “Rabbit-Proof Fence”, Noyce was casting his next film, “The Quiet American”, starring Michael Caine and Brendan Fraser, and approached Gabriel to do the score on the much bigger film.

Noyce also told Gabriel about the other feature he was working on, a little Australian film with a much smaller budget. Within 48 hours, Gabriel told Noyce he would do the latter, for free.

“When I was in London for “The Quiet American” looking for cast, I met Peter and I told him the story of “The Quiet American” that I was about to shoot, and “Rabbit-Proof Fence” that I just shot. And I said to Peter, ‘One of these movies, I can pay you a million dollars to do the music. That’s “The Quiet American” and the other one, I can’t pay anything’. And I said, ‘Think about it. If you’d like to do either movie, I’d love you to do it’. So, two days later he rings and he says, ‘I’ll take the one that pays nothing’.”

“He spent 10 months on that soundtrack”, Noyce adds.

Noyce says Gabriel had a major impact on the film.

“While we were cutting the movie, I went off and shot “The Quiet American”. And during that time, Peter did the score and the first thing he said was, ‘Could you please send me all samples of all the sounds that those children would’ve heard on their journey. The wind, the rain, the water, the birds, their footsteps, everything’. And what he did was he took those sounds and orchestrated them and made them the instruments that you hear in the movie,” Noyce remembers.

Looking back on the film 20 years later, Noyce says he is proud of its legacy, as the first major film to address the Stolen Generations, and believes it proved there was an appetite for films on the Indigenous experience.

“The Australian public were waiting for the vehicle that would allow them to embrace Indigenous experience, not to reject it. And that was the wind that was blowing”, Noyce says.

Six years after the film was released, in 2008, Kevin Rudd would make his historic apology on behalf of the Government to the Stolen Generations.

Not only a major success in Australia, the film was also a huge hit overseas in the U.S., U.K., Canada and South Africa, where other countries’ Indigenous populations had experienced the disastrous impact of colonialism.

“It was very popular and ran a long time in certain cinemas in North America because both the United States and Canada had similar policies towards their Indigenous. There had been attempts to reeducate them, to integrate them into white society. There’d been attempts to eliminate their language and traditions. And in England, of course, where the film also played very strongly. This was a piece of their own colonial history. And we found really strong support for the film in South Africa for obvious reasons, in places like Turkey, so many countries that had their own version of similar policies. So, it wasn’t just an Australian story, it was a universal story,” Noyce recalls.

While Noyce says Australian legislation has come a long way in the years since “Rabbit-Proof Fence” was released, he says he hopes the apology will be just one step in the chain of changes to come towards reconciliation.

“We know that [less than] 10 years later, there would be an apology by Kevin Rudd in the Australian Parliament. It was the beginning, hopefully, of major Government action towards Indigenous Australia, and we continue to see the recognition of Indigenous ownership of the land, the ongoing celebration of Indigenous culture and its value to Australia,” Noyce says.

“Hopefully the apology [and the film] will just be a part of legislative changes to follow,” he adds.