Tony Gilroy is trying, unsuccessfully, to look relaxed.

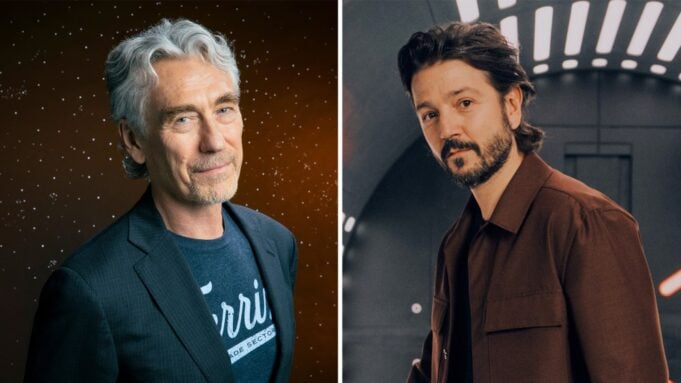

We’re sitting in his Los Angeles hotel room less than two weeks before “Andor” — the Emmy-nominated, Peabody-winning “Star Wars” series he created — concludes its second and final season on Disney+. Because of the vagaries of their schedules, Diego Luna, the star of the show, is joining us via Zoom from Mexico, and Gilroy’s been listening to him wax rhapsodic about the first time they met. It was the summer of 2016, and Gilroy had been hired to oversee reshoots on “Rogue One,” the one-off “Star Wars” prequel about a team of rebel spies, led by Luna’s Cassian Andor, who sacrifice their lives to steal the plans for the Death Star.

Luna went into their first dinner intimidated by Gilroy’s reputation as one of the industry’s most trenchant and skillful filmmakers — from the “Bourne” movies to the Oscar-winning “Michael Clayton.” They wound up conversing into the night.

“It was beautiful,” Luna says. “Tony, when he starts talking, you just get immersed into a little universe that he paints for you. It was like, holy crap, I feel like I know this guy, and it’s been just three hours of my life. He was so generous and open.”

Luna is about to continue, but Gilroy can’t take it anymore. He puts his hands to his face and interrupts.

“I’m sick of this now,” he says — so softly, I ask what he said to be sure I heard him correctly.

“Yeah,” he confirms, adding with a laugh, “The miracle of me!”

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

Despite Gilroy’s self-deprecating sarcasm, for many “Star Wars” fans, “Andor” has indeed been nothing short of miraculous. Conceived to cover five years of Cassian’s life right up to the events of “Rogue One,” the series has used the character’s transformation from a two-bit thief to a hard-bitten insurrectionist to tell the sprawling story of everyday people who make the choice to fight against, or collaborate with, an autocratic regime. Gilroy drew upon his lifelong study of historical revolutions to inform the show’s interweaving storylines of payroll heists and gulag escapes, street riots and false flag operations, squabbling freedom fighters and pitiless secret police. All of it is in service of exploring, as Gilroy puts it, “what happens when history comes knocking on your door” at a time when the specter of fascism and oppression has rattled the foundations of democracies across the globe — including the United States.

While “Star Wars” has invoked real-world horrors since its inception 48 years ago — it’s the first time many of us heard words like “stormtroopers” and “rebellion” — Lucasfilm’s transformation into a multibillion-dollar Disney subsidiary in 2012 has delivered a mixed bag of controversial hits (“The Last Jedi”), successful franchise extensions (“The Mandalorian”) and inert duds (“The Book of Boba Fett”). What’s so astonishing about “Andor,” and has united critics and fans alike in acclaim, is how the show has harnessed the familiar, even comforting, motifs of this cultural institution to deliver a story so bracing and immediate and wildly ambitious. “Andor” summons images of Ukraine, Gaza, Kabul and Hong Kong alongside references to the French Revolution, Oliver Cromwell and Nazi propaganda; while the show may take place a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, it feels more about the here and now than “Star Wars” possibly ever has.

“I’m writing about how I feel about all the revolutions, about all the insurrections,” Gilroy says. “People legitimately fail to recognize how puny their individualism is. The narcissistic belief that you live in some unique time — it’s shocking. We all do it. I do it. That is not the pattern of history.”

As Gilroy, 68, and Luna, 45, talk in-depth about the distinctive process behind their 24-episode series, it becomes clear that, beyond a combination of vast studio resources and absolute creative freedom, it was their dedication to making the most of what Gilroy calls “a one-time opportunity” that allowed “Andor” to succeed.

Des Willie / Lucasfilm

How would you say your creative relationship has evolved over the course of making “Andor”?

Tony Gilroy: [Pointing to Luna on the screen] When we talked about actually doing it, we were at the Bowery Hotel, and we had lunch and we were like, “I don’t know.” We knew we liked each other. We knew we could work together. I told him how crazy I was going to be at the top, and we’d see what happens.

Diego Luna: I remember one phone call before he was going to have this long meeting to pitch his idea. I was in Mexico, and he said, “I figured it out. This is the arc. This is what I want to do.” It sounded bold, cool, different. It was very specific. These days people talk a lot about stuff they might never do to sell things, and then they figure out what they can actually do. With Tony, that’s never the case. You’ve got to be careful because what he says is what he will do. He commits.

COVID made us shoot the first season in bubbles far away from each other, working a lot like how we’re doing this interview. The exchange was with the material. I’m going to get a little romantic, but there was a moment of connection with Tony on set when we were working with those scenes as actors — Tony was in New York — and it was like, holy shit, how lucky we are to be working with a guy that we cannot hug or have here with us. But for me, Tony is someone that was there every day. It’s a presence that I feel always, even though we were in different time zones.

Tony, how do you feel when you hear something like that about yourself?

Gilroy: I’m embarrassed. I mean, all the things that you want to hear. At the same time, you’re like, oh my God, what’s this going to look like in print? I do think that, because we built the show in the COVID Zoom model, it forced me to be more present on the page than I might have been if I’d been at Pinewood every day. I’ve never articulated it exactly like that before, but that was how we did it. It forced me to be on the page so much more precise than I would be — even on a film I was directing, really.

Luna: It just makes you question, shit, is this the best way to do it? Probably it is. I can tell you that directors talk about this show with a feeling of ownership that TV doesn’t normally give directors.

Gilroy: Yeah, our process was really weird, but it was good for us.

What made it weird?

Gilroy: We take everything to the absolute utmost preparative level you could possibly take it. Every single stage direction, every moment of tempo, every color of every sash, the provenance of every prop, every possible confusion is all aired out. In the end, it’s so absolutely articulated, and then we give it to the directors and the actors, and we never have a writer on set. The only time I ever visited set was ceremonial, or to say hello, or to make sure everybody remembered I was still on the show, that I was still alive.

And as Diego said, the directors enjoyed that process as they made their block of episodes?

Gilroy: Most television directors, I’m not an expert on it, but you’re expected to do coverage. Toby Haynes directed the first block [of episodes of Season 1]. I was in New York with my brother [executive producer] John [Gilroy], and we had a cutting room on 86th Street around the corner from my house. The first week, the first dailies came in, and they were terrible. I was like, “What the fuck is this? We’re starting off the show, and it’s really boring. What is this?”

[Executive producer] Sanne [Wohlenberg] called me back that day and goes, “Well, we’re reshooting this.” And I’m like, “Can we do that the first week?” She goes, “We have to. It sucks. And you have to tell him.” I never did this before or since: I made a complete storyboard for how that [episode] should go, and it freed Toby up. “We don’t want coverage. We want intentional directing. Direct this like your life depends on it.” After that, he never needed to be told anything. That was our mandate for all the directors. You know what our grammar is. We don’t want to have the traditional “Star Wars” idea that you show a gigantic crazy place, there’s some people down there talking and then you find out what they’re talking about. We start with the people, and they just happen to be in someplace spectacular. But other than that, make these pages come alive.

Luna: I have a friend that works on the show. At the beginning, he was like, “I can’t believe I’m asked to do so much preproduction time.” After he did the show, he was like, “Thank God we did that.” It brings a very interesting dynamic on set. You’re not working for someone else’s approval. It’s beautiful to see directors so inspired to work, and do 13 takes of one shot because they really want to get it the way they pictured it.

And Disney and Lucasfilm gave you similar freedom?

Gilroy: Total freedom. I think Disney was freaked out the first season when we started saying that. But we finally were like, “Don’t you realize that for us, it’s a miracle?” What they did is such a huge gamble, and it’s such a credit to them. They really were Medicis on this. They watched what we did. We had economic reasons for changing things, and certainly conversations on a weekly basis about that as the shrinking pie came around. But no one ever said, “Man, don’t do this,” or “Do that,” or “Hey wait, what are you doing?” Never. It’ll never happen again for me, I don’t think.

Diego, for Season 2 when there weren’t COVID restrictions, were you on set when Cassian wasn’t in the scene?

Luna: If I was in London, yeah, I would spend time there. But also on the second season, I spent a lot of time with my family that I couldn’t do on Season 1.

Gilroy: We get dailies every morning. I wake up at five o’clock in the morning and I have a whole tranche. Everything’s visible. The only other thing that was really, really valuable is I would ask the director to call me on Sunday night, and we’d have a half-hour, 45 minute conversation about what was coming up during the week. Sometimes it’d be like, I can’t believe we were going to do this without this conversation. Sometimes it was just really simple, easy stuff.

Also, Diego is one of a dozen actors that are on the show for the whole run, and they are deputized as much as anybody to make a temple of their character and their storyline. We run a show where everybody knows everything. It’s a highly communicative show, but sometimes the actors are far more informed than the director may be about the moment that’s happening and its importance.

Luna: The pre-production also happens for us. If I wasn’t shooting, I had rehearsals for the next block. I had a meeting with the director for the next block. Directors were visiting set before they started their block, watching someone else’s work. Communication flows very well in this family. We got really good at it because we started in a moment where one of the biggest problems was how are we going to communicate if we can’t be in the same room.

What has it been like for you both to see people drawing so many current, real-world parallels to this show?

Gilroy: Well, the show was supposed to come out a long time ago, but for the strikes. And the digestive process of bringing something from your desk to an audience is a pretty long process. Usually, you’re carbon-14 dating what happened rather than being prescient.

So this sounds like an “answer,” but it’s the truth: The repeating patterns of revolution and authoritarianism, and all of the attendant things that go with that, they just replicate. Our show is about what happens when history comes knocking on your door, and if people find history knocking at their door, there’s probably all kinds of places they can look for references. We just happen to be the pick of the litter this week.

Diego, how about for you?

Luna: I think people are really asking, “How can you do this material with these characters?” Any piece of wonderful and honest writing becomes personal. Even though we are in this galaxy far, far away, and we are using all the tools of something everyone thinks they understand perfectly, we’re showing the intimate life of people that were never in frame. The camera didn’t stay with them. That’s why I think this has become so interesting to think about, the relevance of the lives of these people to our own lives. But that’s what is supposed to happen. It’s why we do it.

What we should be talking about, you and I — because he’s not going to talk about it [Gilroy laughs] — is what’s behind the writing of this show, which is someone’s interest, context and family and all of that. The specificity he writes with is just reflecting the richness of his perspective. You and I, we go, like, “Shit, how did he know that we wanted to hear that?” But it’s because he’s being honest with his own needs and reflecting what goes on in his mind.

The final episodes of “Andor” lead directly into the events of “Rogue One.” Diego, what was it like for you to be back on the set, to wear Cassian’s costume from the movie again, to be sitting in the cockpit next to his droid K-2SO — all of it?

Luna: I was getting emotional by everything. I would go into tears many times a day. I thought it wasn’t going to be possible, that we were not going to get there. It was a triumph in many ways.

One other thing about that ep: The director and the DOP are Mexican. This is something I just realized a few days ago. I was speaking my language with people I’ve known for 25 years, making jokes in the way I joke at home, but I was on the “Star Wars” set. That feeling of like, shit, this became home. I’m so at home that I’m here with my homies fucking making jokes in Spanish, and the AD, who is Scottish, is trying to catch up. In “Rogue One,” I was the one catching up, and here it was the other way around. It felt very special.

You said in your Actors on Actors conversation with Hayden Christensen two years ago that before “Andor,” you hadn’t realized that you could make something with artistic integrity that was also hugely popular.

Luna: I grew up in a house where my father was doing theater and opera, and [believed] everything else had no integrity, was following commercial rules that ruin the creative process. That’s what I had for breakfast all my childhood. And then I lived in Mexico where we were doing 10 movies a year when I started, and they were all paid by the government, basically. So that’s where I come from.

When did that realization start to hit you?

Luna: I would say in the first third of the shooting of the first season, when the complexity that Tony was putting on the page was actually being explored and deepened in the process of shooting, and getting through it without receiving any restrictive order of like, “You got to stop; this is going too far.”

I don’t know if I can expect this to happen again. I’m still doubtful. But I do think that this show has used the idea of approaching a new format for Lucasfilm. It felt to me every day that we were honoring filmmaking in the way I learned it. I’ve never had all these tools on a set that is driven by creativity and freedom.

Tony, your father, Frank D. Gilroy, was a Tony- and Pulitzer-winning playwright — how did that affect your approach to popular material?

Gilroy: [Points at Zoom screen] His experience with his father is the far extreme of, “This is art, everything else is shit.” In my house, it was one for me, one for them. That was the philosophy. You do your work for yourself, and then you cash in. And there’s honor in all things. I’ve had prior experience getting over with things that I thought were quality and having them hit the number. I had that feeling of winning before. So it wasn’t a shocking first time.

Luna: But for me, there is a shock. We did a show that people celebrated for the same reasons we wanted to do it. And it never felt like we lost control, that we didn’t know which voice we were following. That’s the moment when you go like, holy crap, is this possible? Is it possible to have such gigantic machinery being driven by one person? I still don’t know if there’s other examples of this in TV. I know in film there are, but I don’t know if in TV.

Gilroy: Oh, I think so.

Luna: This is the first for me.

A lot of that reaction, I think, comes from the revelation that “Star Wars” can handle something so mature and complex and human scaled. Audiences have an expectation of what legacy franchises like this are supposed to be like, and you both upended that.

Gilroy: But it’s just a matter of — I mean, look at “Logan.” Why is “Logan” so good? It is [screenwriter] Scott Frank and [director] James Mangold coming in, inspiring Hugh Jackman and going, “Let’s just really nail one down.” It’s the people doing it. It’s the commitment to doing it. It’s whoever’s going to be in charge, what the expectations are, and it’s how ambitious people want to be.

Luna: And I think the audiences are showing up.

Gilroy: Yeah. Every single thing could be used as a host organism for something wonderful.

This interview has been edited and condensed.