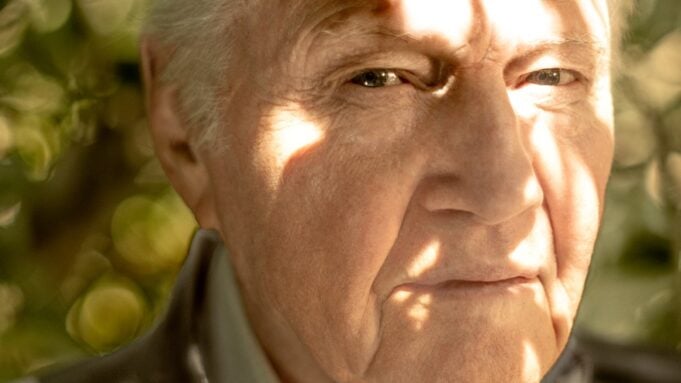

Jon Voight keeps moving. The 85-year-old actor is shadowboxing, his footwork nimble for a man of any age, let alone someone older than even Joe Biden and Voight’s friend Donald Trump.

He pauses and arches an eyebrow and becomes a matinee villain. “You think you’re tough. I’ll show you tough.”

Today, we’re outside his Beverly Hills home. There’s a pool and a driveway where Voight designed the pavement that features tiny ducklings, rabbits, monkeys and a dragon etched into the cement. Near the entrance are the words “Wots Modder Wot You Jonny,” in honor of his Czech grandfather who never quite mastered English.

I’ve talked with Voight many times over the past year, and he is always engaging. But the presence of a photographer has kicked him into a high gear. He picks up a plastic rabbit in his yard and speaks to it, Elmer Fudd style. “Wabbit, I told you to stay away from me.”

His antics have a manic “Let’s put on a show” quality to them, not unlike the comedy stylings of Sid Caesar, one of Voight’s boyhood heroes. Today, Voight doesn’t resemble any of the troubled men tortured by circumstances he’s played in his six-decade career, including would-be hustler Joe Buck in “Midnight Cowboy,” paralyzed Vietnam vet Luke Martin in “Coming Home,” and Ed Gentry, a suburban everyman turned avenging killer in ”Deliverance.” Today, he’s all loopy grandpa, which is a role he plays for his six grandchildren now that he has reconciled with his once-estranged daughter, Angelina Jolie.

Camping it up for the camera, Voight seems to be reprising a recent note — one he plays in Francis Ford Coppola’s dystopian “Megalopolis,” where his Crassus reigns as a wine-addled emperor over a decadent New Rome, a fictional version of a future New York City. Any film with Shakespeare shoutouts and Ayn Rand references is bound to be a bloated mess, and Coppola’s passion project features a high ratio of great actors giving the worst performances of their careers. Still, Voight shines in a gob-smacking way as the richest and horniest man in town. He sports a Caesar cut and gets busy with a woman a half-century his junior named Wow Platinum. In the film, Voight staggers around, a silk-pajama-clad Lear on a bender, dropping bons mots like “What do you think of my boner?” before shooting an arrow through his lover’s heart. One critic wondered if Voight knew he was on a movie set during his scenes. I assure you, for “Megalopolis,” that’s a terrific compliment.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

Coppola’s film, which premiered last spring at Cannes, is all about the fall of an empire, and this is something that concerns Voight greatly.

On May 31, shortly after the conviction of Donald Trump for tax fraud, Voight posted a video lacerating President Joe Biden. In it, Voight, seated in front of an American flag, unleashes a stream of invectives that are all the more startling if you’ve spent time with the otherwise soft-spoken actor. “We’re allowing this sick President Biden to give permission for all to steal, cheat, lie and kill,” he says, “and no one is paying the ultimate price for this. We must stop these animals.”

No one is spared Voight’s seething right-wing political opinions, including his daughter, who he feels has fallen victim to antisemitic subterfuge. (“Angelina wishes him well but does not speak about him publicly,” said a source close to the actress.) He says her politics are, to put it mildly, not his, while his are the subject of an endless circular conversation — especially now that Trump is on the upswing. The actor is a staunch supporter of Israel, most recently its response to Hamas’ Oct. 7 attacks, and Jolie is a longtime refugee activist, currently decrying Israel’s killing of women and children in Gaza. In our conversations, Voight never lets it go, criticizing her Palestinian stance repeatedly, like a candidate going after an opponent in a 30-second ad. “She has been exposed to propaganda,” he says. “She’s been influenced by antisemitic people. Angie has a connection to the U.N., and she’s enjoyed speaking out for refugees. But these people are not refugees.”

Back in Beverly Hills, Voight keeps it light. We move into the house, and he bounds up the stairs to his bedroom. Hanging on the wall are faux stones from the 1999 TV miniseries “Noah’s Ark,” in which Voight portrayed the titular character. There’s his easel and a large photo of his father. He puts on a robe and spreads out on his bed. A giant smile crosses his face, and his blue eyes are lit. “What else do you need?”

Once the photographer leaves, Voight falls into a chair at his dining room table. He looks tired. It has already been an exhausting summer. Not only is he doing press for “Megalopolis,” but he’s getting ready to move from the house where he’s lived for the past two decades.

His home currently resembles a set being struck down. There are boxes of books scattered everywhere. His Oscar for “Coming Home” is somewhere on the premises. In the living room, large framed photographs of Mother Teresa, Martin Luther King Jr. and various Indian yogis dominate the space. Upstairs, photos of Jolie and her ex-husband Brad Pitt are prominently displayed, including a 2008 People magazine cover of the couple holding newborn twins. (The family photos cut out of magazines roughly correspond with the times when Voight and Jolie were estranged.) Downstairs, there’s a sketchbook and a drawing for his granddaughter Vivienne that he will send her wishing her a happy birthday and congratulating her on the success of Broadway’s “The Outsiders,” which Voight says she brought to Jolie’s attention, and they went on to produce together.

Voight’s doting side is one that’s far removed from the gallery of eccentrics he’s come to specialize in on-screen. Crassus is just the latest in a line of gonzo performances in a 60-year career that includes Voight as Voight biting Kramer’s arm on “Seinfeld,” an appearance as a blind Indian in Oliver Stone’s “U Turn,” and an Ahab-like snake hunter in “Anaconda,” who gets eaten and regurgitated by his own white whale. The more insane the part, the more outrageous the challenge, the better for Voight.

“I appreciate the great ones like Spencer Tracy and Cary Grant,” he says about his favorite actors. “But for me it was always Lon Chaney with his makeup bag.”

Two of the best examples of Voight’s approach to morphing into characters include his appearances as Nate, a criminal operator with some startling facial disfigurements in “Heat” and his chameleonic Oscar-nominated turn as sportscaster Howard Cosell in “Ali,” both Michael Mann films.

“For Jon, the transformation, that’s the adventure,” says Mann. “The adventure is the wild way he gets to transform himself to get into this character. As a director, I know enough about Jon that the further into outer space the idea is, the more attractive it is.”

Mann says that Voight spent more than four hours every day in makeup being transformed into Cosell. Between takes, Voight and Will Smith, as Muhammad Ali, would verbally spar in character to the delight of hundreds of extras. “I was trying to set up shots, and then all of a sudden, these guys are doing ad-libs so good I’m trying to write it down,” says Mann.

Praise like that is what keeps Voight working in lefty Hollywood even as he compares Joe Biden to Satan and muses that George Soros is hell-bent on destroying the country. Hollywood is in a recession, and Trumpists like Scott Baio and Kevin Sorbo have been banished to right-wing productions and reality TV. Jon Voight? He has appeared in three movies in the past 24 months.

Sometimes, over the past year, Voight called late at night just to say hello. We spoke of Blake’s “Jerusalem,” our children, Renaissance art and how Burt Reynolds broke his tailbone doing his own stunts in “Deliverance.” There were two Jons in our conversations: the cultured and kind acting icon, curious about art and poetry, and the right-wing warrior ripping Biden and dismissing Palestinians as frauds with no claim to the Holy Land.

Under normal circumstances, an actor of Voight’s stature and age would be feted at festivals and film schools, but that’s not been the case with Voight, and it undoubtedly connects to his politics. Instead, the actor cuts a forlorn figure, showing up at the occasional party or art gallery in L.A. with his son, James Haven. At a gallery opening in Beverly Hills in December, a visitor whispered to a friend, “That’s Jon Voight — he says some crazy-ass things.”

Recently, Martin Short’s talk-show alter ego Jiminy Glick turns to actor Sean Hayes and says, apropos of nothing, “What makes Jon Voight so angry?” It’s a good question.

I meet Voight for the first time at a Santa Monica restaurant. He still has the movie-star blue eyes and wide smile, but depending on where you are sitting, you see two different sides of the actor. His profile from the left features the cheekbones that made him famous. From the right, Voight’s face is dented and looks menacing.

That day, Voight tells me he wants this story to be centered on his acting. That lasts for the first 20 minutes of our relationship. He is showing me Renaissance-era paintings on his phone that he took on a recent trip to Greece, when a middle-aged woman approaches our table, holding a loaf of challah just purchased for her family’s Shabbat dinner. Voight waves her over. She grasps his age-spotted hands: “I just want to thank you for all you have done for Israel. It means so much to all of us.”

Voight thanks the woman, but she isn’t done. “You should play Bibi in a movie. You would be perfect!”

Voight laughs. “He’s a great, great man,” he says, “but I’m not going to play him.”

Remarkably, an almost identical scene occurs a few months later, when Voight and I meet at the Beverly Glen Deli, his favorite hangout. Same-age woman, same sentiment. (I put the chances of this being an elaborate setup at less than 10%.)

Voight often acts startled when bystanders, reporters and legendary directors want to engage with him on politics, despite his X and Instagram posts and occasional Fox News appearances. (His videos in support of Trump and Israel have millions of hits.) At the Cannes press conference for “Megalopolis,” Coppola spoke in apocalyptic tones of the dire state of American politics. “There is a trend toward the more neo-right, even fascist division, which is frightening,” Coppola said. “Anyone who was alive during World War II saw the horrors that took place, and we don’t want a repeat of that.”

“Megalopolis” has a definite anti-Trump vibe, with Jan. 6-style riots featuring red-capped thugs and Confederate flags. Some have suggested Voight’s Crassus is a buffoonish version of Trump. I ask Voight about it.

“I didn’t see that,” he says. “If I had, I would have told Francis he was out of line.”

Coppola remains diplomatic when I ask about Voight. “Working with Jon is always an interesting, potent and joyful collaboration,” he says. “He’s an artist, and I enjoyed our time together making ‘Megalopolis.’”

At Cannes, Coppola played it a little looser. He turned to Voight after he finished venting and said, “Jon, you have different political opinions than me.” Then he passed him the microphone. Voight didn’t engage, instead offering generic praise and saying that Coppola simply wants to make “a better world.”

Back in Los Angeles, Voight sounds hurt.

“I’ve been telling Francis to make that movie for over 30 years,” he says, looking genuinely confused. “I really don’t know why he thought that was the time to talk about our politics.”

After Cannes, Voight stopped in New York on his way back to take in “The Outsiders.” “It was amazing,” he says proudly. “Angie is amazing.”

Father and daughter seem to be getting along better these days. That is, except when Voight is attacking her over the Israel-Hamas war. Jolie has been an advocate for refugees for more than two decades. She has worked on projects bringing attention to genocides in Southeast Asia and in the former Yugoslavia. People listened when she released a statement last November on the Israeli invasion of Gaza.

“This is the deliberate bombing of a trapped population who have nowhere to flee,” wrote Jolie on Instagram three weeks into the conflict. “Gaza has been an open-air prison for nearly two decades and is fast becoming a mass grave. 40% of those killed are innocent children. … Whole families are being murdered.”

Voight responded with his own post on Twitter a day later. It started, “I’m very disappointed that my daughter, like so many, has no understanding of God’s honor, God’s truths. This is justice for God’s children of the Holy Land. ….”

This seemed massively counterproductive, because Voight has spent the past 30 years trying to right the wrongs of his wild years with his children. And yet, during our conversations, Voight, who keeps praising his daughter’s talent and accomplishments, cannot resist repeatedly schooling her on his political worldview. Voight’s relationship with his children has been fraught since their mother, Marcheline Bertrand, divorced him in 1978, citing adultery. During his children’s adolescence, Voight wasn’t around much, and over the years, there have been schisms, silence and reconciliation.

“I love my daughter — that’s No. 1,” he says. “I am happy when Angie is happy.” His eyes begin to well up with tears. “When she’s having a tough time, I’m having a tough time. When she is down, I’m down.”

That sentiment makes his public attacks on his daughter all the more puzzling. For instance, in May, we meet for coffee in Hollywood, and Voight offers long monologues on the history of the British Mandate for Palestine and the Ottoman Empire’s decline that, he says, conclusively prove Jolie’s position is profoundly wrong. He then falls back on an old chestnut of Hollywood detractors.

“Angie, I think she hasn’t been available to this information because in Hollywood people don’t share this kind of stuff,” he says. “They’re way off. They have no idea what’s going on. It’s a bubble.”

Leaving aside the fact that Voight lives in Beverly Hills and had us meet twice in the shadow of studio lots, it’s hard to believe that Jolie isn’t able to access the right information. I bring this up, and he disagrees. His face goes red, and beads of sweat appear on his forehead. “I love my daughter. I don’t want to fight with my daughter,” he says heatedly. “But the fact is, I think she has been influenced by the U.N. From the beginning, it’s been awful with human rights. They call it human rights, but it’s just anti-Israel bashing.”

Heads turn in the café. Voight is talking louder than usual and continues without taking a breath. “She’s ignorant of what the real stakes are and what the real story is because she’s in the loop of the United Nations.”

He finally stops and sighs. “Maybe we shouldn’t talk about all this politics stuff.”

So we talk about the rape scene in “Deliverance.” Voight is convinced that only Ned Beatty could have done the “Squeal like a pig” scene that shocked moviegoers in 1972. “He was so human. Anyone else, and it would have come off as camp.”

We finish our coffee and say our goodbyes. That night my phone rings. It’s Voight. “Let’s meet again,” he says. “We can talk about how Angie is coming across.”

Everett Collection

Voight grew up in Yonkers, the middle son of a golf pro and a stay-at-home mom whose great-uncle was an isolationist and a staunch Joseph McCarthy supporter. Barbara and Elmer Voight must have done something right because Voight’s brothers also rose to fame, one as a volcanologist and the other as the writer of the Troggs classic “Wild Thing.” His parents nurtured his artistic side, and filled their small apartment with his paintings as a 3-year-old. He still paints, but says he gave up his obsession when his dad took him to the movies when he was 8. “I knew my painting couldn’t keep up with all that action and motion,” Voight says. “I wanted to perform.”

Voight’s father worked at a Westchester country club featuring predominantly Jewish members shunned by WASP golf courses. It left Voight with a specific idea of how an oppressed people should rise above their status.

“As a little boy, I remember seeing a Life Magazine picture of a boy in a striped suit behind barbed wire,” Voight says on more than one occasion. “And I thought, ‘That could be me.’ I identified with the suffering of these kids. What I knew very early on from my father’s work and the dinner table was that the people who started this club couldn’t get into other clubs when they came here from Europe. And so what did they do? They simply gathered together, got some money, bought land and made their own club. They didn’t riot or protest. From then, I was connected to their culture.”

He is convinced that his father’s relationships with the Jews at the club changed him forever and allowed him to have the life he has lived. In 2018, he told Fox News’ Mark Levin that his father’s brother and two sisters couldn’t compare to him. “He was so superior in every way,” Voight said. “Not to demean them — they were very nice people — but they just didn’t have the grace that he had. And I said to myself, ‘You know something? My dad was raised in the Jewish culture. That’s who he is.’”

By the transitive property, Judaism made Jon Voight possible since it was his father who encouraged his dreams first while in high school and then at Catholic University in Washington, D.C.

Voight told me how in college he worked on his acting technique by going on a date with a different girl every week. “I think they appreciated me because I wasn’t trying to score,” Voight says. “I’d listen and try to talk about what they wanted to talk about. I think it made me a better actor.”

Voight also stumbled across theater critic Kenneth Tynan’s book “He That Plays the King” and made copies of all his reviews of Laurence Olivier’s performances. “I knew it might take years or decades, or I might not even get there, but that was what I wanted to aim for.”

Voight told his father that he was moving to New York City after graduation to become an actor. His dad worried about how he would make a living. He suggested an idea not far from the Joe Buck character arc. “He thought of buying a driving range,” says Voight. “He knew I was charming with ladies and could bring them in, and I could make a living and then do auditions on the side.”

The plan never materialized. Instead, Voight cobbled together a career on Broadway before being cast by John Schlesinger opposite Dustin Hoffman in “Midnight Cowboy.”

I wonder what his father thought of his son after he became a movie star, but Voight doesn’t want to get into it.

Later, I give him a book I wrote about my Navy pilot father who was killed in a plane crash when I was 13. My phone rings that night. It’s Voight. He blurts out something about his past: “My dad died when he was 63. It was a car accident, and my mother was driving.”

I don’t know what to say. I tell him that must have been so hard for him.

“That was a long time ago,” he says. “OK, lad, have a good night.” And then he hangs up.

Everett Collection

Voight’s support for Israel wasn’t controversial for most of his life, even if his affection for the oft-accused, never-convicted Benjamin Netanyahu seemed over-the-top. But then came the savage Hamas attacks that slaughtered more than 1,100 Israelis, including 38 children. Initially, Israel had near-global support outside the Arab world. Then, as Israeli bombs leveled Gaza, the United Nations and human rights activists began suggesting that Israel was repeating the mistakes of America after 9/11, inflicting rage-filled indiscriminate violence on the Gazan civilian population resulting in the deaths of an estimated 35,000 Palestinians, many of them women and children, as neighborhoods were razed in the pursuit of Hamas terrorists.

Voight doesn’t see it that way. He believes the whole concept of a separate and distinct Palestine is an antisemitic con perpetuated by Arab countries hell-bent on the destruction of Israel with the assistance of the U.N. Voight maintains that the key point in what he calls “the fraud” was when the U.N. granted refugee status to Arabs who had tried to destroy Israel in the country’s 1948 war for independence. “Every year, the U.N. features more antisemitic motions against Israel than the ones offered against Iraq, China and Syria combined,” he says.

Voight holds a special contempt for activists who have embraced the U.N. position that there are more than 5 million Palestinian refugees in Gaza and the West Bank. “They are so naive,” he says. “They’re dupes who never get outside of their bubble.”

Unfortunately, according to Voight, one of those “naive dupes” is Jolie.

There’s a profile of Voight from The New York Times from back in 1979 that captures the demons that he dealt with in the wake of the success of “Midnight Cowboy” and “Deliverance.” “He agonizes his way toward every decision,” said Jane Fonda, his co-star in “Coming Home.” “What his next movie should be. Whether to go out to lunch. He’s a good, tortured person.”

Voight’s agony led him to pass on “Love Story” despite multiple entreaties from producers and an offer of a percentage of the profits that would have earned him $6 million in 1970 dollars. Fifty-five years later, Voight insists he didn’t make a mistake. “‘Love Story’ wouldn’t have been good with me in it,” Voight says. “I would have overly complicated it.”

He spent years trying to center his chaotic and chattering life by devouring books on mysticism and Eastern philosophy. He disappeared from the public eye for most of the 1980s. Mann told me Voight was a regular at Duke’s in Malibu during that era, sitting in the corner, his face obscured by long hair. “I didn’t go up to him,” remembers Mann. “I was a little scared of him.”

“I was too screwed up to act,” says Voight.

Finally, in his 40s, he had a spiritual awakening. He was crying on the floor of his home and asked God why everything seemed so hard. God gave him an unexpected answer: It’s supposed to be hard.

The work came back after that. He got another Oscar nomination for 1985’s “Runaway Train” and appeared in “The Rainmaker,” his first work with Coppola. He also helped Tom Cruise relaunch the “Mission: Impossible” franchise.

There was some accompanying Voight weirdness. He unsuccessfully sued an ex-business partner, Laura Pels, in 1994 after claiming she backed out of investing in his films because he wouldn’t sleep with her. There was another series of lawsuits involving two New Zealand producers over a failed movie project that ended with no assignment of blame but much bad blood.

Voight’s spiritual awakening is the one aspect of his life that the actor is reluctant to talk about in detail. “I get too emotional,” Voight says. He then tells me where I can learn more about it. “I did an interview with Tucker Carlson,” he says. “It’s all there.”

Ron Galella Collection via Getty

Jon Voight remembers when he first met Donald Trump. “It was at a party in New York in the 1990s,” he says. “He came all the way across the room to tell me how much he loved one of my films. I was so impressed.”

Voight has returned the favor exponentially; he compares Trump to Lincoln and Richard the Lionheart and declares his enemies to be less than human. But Voight wasn’t always like this; back in the ’60s, he considered himself a typical Hollywood lefty. But an experience toward the end of the Vietnam War changed that.

In the early 1970s, he was sitting next to a soldier on a flight. The man was on his way home from Vietnam. “He was shaking, clearly had PTSD,” Voight says. “I knew when he got off the flight he’d be spit on and called a baby killer.”

Voight is repeating a long-dismissed myth that soldiers returning from Vietnam were spat on and called murderers by their fellow Americans, but the viewpoint led him to the role of Luke Martin, a paraplegic Vietnam vet in “Coming Home.”

Voight’s takeaway from “Coming Home” wasn’t that Vietnam was a tragic mistake that cost thousands of American boys their lives in a pointless war. No, Voight thinks we should have stuck it out. He measures a tiny distance between his thumb and forefinger and says, “We were this close to winning. Then there were the protests and the riots.”

Most military historians disagree with Voight’s analysis. The idea that our country would not have suffered an ignominious defeat if only the military had been given endless resources and not been stabbed in the back is as old as history. Still, it set Voight on his political path. While he campaigned for George W. Bush and Mitt Romney, it was the rise of Barack Obama that infuriated him.

In a Fox News appearance in 2014, Voight said, “Five years ago, I stated that Obama would take the country apart piece by piece — that he would cause a civil war in this country. In hindsight, we can see how many things have come to pass.”

Voight has been rhetorically at Trump’s side since the former president announced his first candidacy in 2015. He still believes Obama is pulling Joe Biden’s strings and calls the current president a mastermind of the largest political crime syndicate in American history. Trump’s shortcomings are dismissed as nothing more than propaganda coming from Democratic Party political conspirators. I ask him if he seriously thinks Trump is the equal of Abraham Lincoln in the pantheon of American presidents, as he has repeatedly stated. “Absolutely,” he says. “Who else has faced greater challenges and enemies since Lincoln?”

I immediately think of FDR but say nothing.

It speaks to Voight’s talents that his inflammatory rhetoric has not stifled a late-career renaissance, particularly Voight’s seven seasons on “Ray Donovan,” where he added to his fractured-masculinity arsenal with his role as Donovan’s manipulative ex-con dad, Mickey. Voight says the key is that he never talks politics at work, and that’s why he took great offense when his “Ray Donovan” co-star Eddie Marsan sent this tweet with a picture of him and Voight on the set of the show: “Hey America, I know this is the most important election ever & the survival of your democratic institutions and the soul of America is at stake but … can we just take it back to me for a second. Please vote for Joe Biden, I can’t spend another 4 years listening to this bullshit.”

This did not please Voight. His voice rises when I remind him of the tweet: “If he is saying I brought up Trump on set, that is a lie.”

But there have been some benefits. A fan tweeted praise of both Voight’s acting and his patriotism in 2019: “Academy Award winning actor (and great guy!) @jonvoight is fantastic in the role of Mickey Donovan in the big television hit, Ray Donovan. From Midnight Cowboy to Deliverance to The Champ (one of the best ever boxing movies), & many others, Jon delivers BIG. Also, LOVES THE USA!”

The fan was Donald Trump. The same year, Trump gave Voight the National Medal of Arts and the National Humanities Medal. I ask Voight if he’s proud of the recognition. He waves me off. “I don’t care about all that stuff. I only have a few years left, and I want to spend them trying to save our American way of life.” He gives an actor’s pause. “It’s slipping away forever.”

AFP via Getty Images

After the Fourth of July holiday, I get a message from Voight asking if we could meet for a quick lunch at the Beverly Glen Deli before he leaves to shoot a film in Bulgaria. The request seems odd: We had already said a last goodbye at his house. I wonder what’s left to say and suspect he’s going to try to take back the words he said about Jolie’s views on Gaza.

The exact opposite occurs. It’s a week after Joe Biden’s incoherent debate performance, and Voight is feeling vindicated. “It’s a disgrace, all the drugs and steroids they’ve been shooting him up with,” he says. He struggles to open the pull tab on a can of root beer. I’m about to reach over and help when he grimaces with concentration and the pop-top relents.

I’ve asked Voight on multiple occasions if I could talk with his son, Jamie, with whom he reconciled a few years ago. I asked first after Voight proudly

told me Jamie was going to direct him in a film this summer. Voight delayed the meeting with Jamie for months, and I gave up the pursuit. But a few minutes into our lunch, Jamie, in his 50s, arrives at the deli. He is well moisturized and dressed all in white, including a skull cap. He launches into a monologue about a number of topics — the film, his involvement in a K-Pop project, his work with troubled children, why Linus is his favorite Peanuts character and how “Star Wars” changed his life. His father beams. I suspect the movie will never happen.

Jamie steps out for a moment. I steel myself for Voight sweet-talking me in an attempt to get me to soften his statements about his daughter. But instead he starts another lecture about Jolie’s Israel information deficit. “It comes from ignorance, like everything else,” Voight says. “It’s like, why are these kids in the universities siding with Hamas, right? It’s because of ignorance. They don’t know the story.”

I realize that this is the key to being Jon Voight. He can sell Coppola’s Crassus because he believes it. He can convince me of his spiritual conversion because he believed that too. But that self-belief — a requirement of any actor, but stronger in Voight than in anyone else I’ve interviewed — has toxic consequences: A true believer cannot comprehend that someone, much less his own flesh and blood, might hold a different view.

I ask him, not for the first time, if he thinks that instead of attacking Jolie on Instagram, he might just pick up the phone. He shakes his head. “It’s hard for me to talk to her about this,” he says with a resigned look. “She doesn’t really want to share this kind of stuff, because she’s of another mind about it.”

Instead, he filibusters about the myth of the Palestinian homeland, referencing the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the British mandate over the Holy Land from 1920 to 1948. It’s the same talk he gave me a few weeks ago, almost verbatim. After about 10 minutes, I gently tell him he explained all of this to me before. He looks confused. “Are you sure?”

At this moment, Voight does not look like a movie star or a soldier for Trump. He just looks lost and agitated, not unlike Biden on the night of his debate.

Five days later, Donald Trump survives an assassination attempt in Butler, Pa. Voight and I connect after a couple of missed calls. He sees Trump’s survival as a sign and speaks of it in messianic terms. “There’s a prophet who predicted there was going to be an attempt on his life,” says Voight. “He was going to go to his knees, and during the moment he was on his knees, he was going to connect with God.”

He then mentions the evil that’s spreading across the world via satanists like Soros. He says we can too easily access it on our smartphones.

I suggest that both sides need to turn down the heat, and that maybe he could take a step back from claiming the Biden Administration is populated by evildoers.

The line goes quiet for a moment. “Well, that’s your opinion,” Voight says. “I’m very careful about what I say. But when I see the attacks on this man, I know they’re coming from a hateful, evil place.”

He transitions quickly to Jolie being brainwashed by antisemitic propagandists and then a familiar stalking horse, Soros.

“What do you say about Soros?” Voight says. “That he seems normal when you talk about him? No. He bought out DAs, he bought out judges, he bought out politicians. You have to have strength. You have to be righteous.”

And that’s when I give up. For all the lovely talk Voight and I had about paintings, poetry and Old Hollywood over deli sandwiches and root beers, it is now clear that he is also coming from a hateful place. He natters on about Marxists and other ghosts, but I tune him out. I tell him I must go, but he wants to end on a hopeful note.

“I’ve been the most outspoken supporter of Donald Trump in Hollywood,” he says with pride. “I’ve been saying he’s the answer, the only answer.” He slips into the third person for the first time in all our conversations. “Now, after this, maybe they will look at Jon Voight in a different way. If Donald Trump is being revealed in this way, maybe they will see a supporter like me in a different light.”

I wish him a good night. There is nothing left to say.

From Variety US