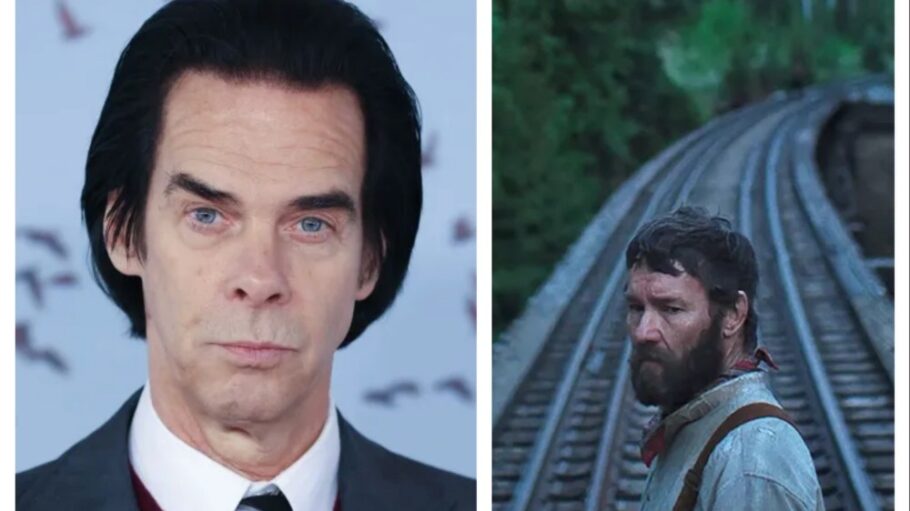

Rock legend Nick Cave might have been a natural to ask to write a theme song for “Train Dreams,” even if he didn’t have any personal connections or ins with the filmmakers or cast. One of his most acclaimed albums, “Ghosteen,” deals with grief following the death of his teenage son, and even his prior and subsequent work is inclined toward a big-picture take on how we grapple with the joys and sorrows of a lifespan spent with and without loved ones, on through his most recent release, “Wild God.”

But Cave did know the movie’s leading man, Joel Edgerton, who had some idea just how close the source novella for “Train Dreams” was to the singer-songwriter’s heart. There were still some slight speed bumps on the way to Cave co-writing the theme, like the fact that he had little inclination to horn in on territory he thought belonged to the film’s composer, Bryce Dessner, of the National fame. And then, as Cave recounts the story, it just happened anyhow, his conscious will about the whole thing notwithstanding.

Variety spoke with Cave by phone while he was in London, wrapping up some tour dates with his longtime band, the Bad Seeds.

How did the request to consider doing a song first come to you? Did you first hear from Bryce Dessner about it, or would it have been (director) Clint Bentley first?

First of all, I think it should be known that “Train Dreams” has always been, like, my favourite book. Whenever I’m asked about books, “Train Dreams” always comes up. It’s a little like (Cormac McCarthy’s) “Blood Meridian” or something to me, just a perfect piece of literature, and especially powerful because it’s a novella — it’s just a short and beautiful thing. So I’ve always had a deep attachment to that book. I know the main actor, Joel Edgerton — he’s an Aussie — and I think he just texted me and asked if I had any interest. And I didn’t really have any time to do it, so it’s quite something. I had all sorts of misgivings about it.

What stopped you from leaping right at it, if you loved the book, apart from the time factor?

I also do scores myself, and the last thing anybody who’s done a score for a film wants is for the producers to come in and dump some song at the end of it that doesn’t relate to the score, just to have a kind of rock song at the end. It happens to us all the time when we do scores; it’s unbelievably insulting. And I didn’t really want to do that to Bryce. But I saw and just really, really loved the film. I thought that they did a remarkable job of capturing this beautiful gem of a novel. But still, I was hesitant about sticking my nose into Bryce’s score.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

Then I watched the film, I fell asleep, I woke up in the morning and I had these lyrics pretty much as you read them in my head, and I quickly wrote them down and really liked them. I never, ever get songs like that. Songs never come to me in that way; it’s like pulling teeth for me to write a song, and this came so easily and beautifully. So I rang up Bryce and said, “Look, I’ve written some lyrics,” and he really liked them, and I said, “But I don’t know how to make that into a song for your film.” Then I watched the end of the film again and realized I could just sing those lyrics over Bryce’s existing score, which was a really beautiful piece of music that drifted into the credit sequence. So that’s essentially what I did: I took his piece of music that he’d already written into the studio, chopped it around a bit to sort of make it more song-like, I suppose, with a bit more form to it, and sang these lyrics over it. The whole thing came very, very easily, and I was really blown away by it. I have to say, it was something about the sparseness of Bryce’s music with the lyric over the top that had something about it that was, for me at least, extremely emotional.

So the way that it came to you was…

Yes, it came to me in a dream. I’m not joking when I say that this is actually what happened. Because I kept thinking “they want me to write a song for it,” and I was on holiday, so the last thing I wanted to do is to have to go into a studio and try and write a song. But the images from the film were in my mind when I went to sleep. And a lot of what I’m talking about in the song is directly related to the film and the book, actually. Usually that sort of thing doesn’t really work. With a song where you actually reference the film itself, it’s definitely a recipe for disaster. But I thought it was a rather beautiful kind of way of summing the whole thing up.

So, literally a song about dreaming that came in a dream.

A train dream.

You mentioned things that are not in the film, and a reference to Elvis stands out, so I’m wondering whether those were taken from the novel or…

Yeah, the Elvis thing is from the book. I just remember this amazing scene where he [the character Robert Granier] goes to the town — I might have this slightly wrong — and this train has passed through with this guy on it that all the girls are going mad over. And he doesn’t know who this person is, but it’s Elvis Presley, with this magical voice. It’s a beautiful part of the book, and it’s not in the film. So there were some images that came out of the book, and some I made up myself.

What did you connect with most about the book?

I mean, I’ve known it for a long time. I like Denis Johnson’s writing a lot anyway, especially the final book that he wrote that was published after his death (“The Largesse of the Sea Maiden”). But the thing about “Train Dreams” was that it was an unremarkable life, you could say, but at the same time, it was, on a human level, an extraordinary life. And the way Denis Johnson writes about that in a kind of plain language … there’s an enormous amount of humility to his language that tells this story that suddenly becomes this crushing story about grief. It’s a weird little episodic thing of him coming back to his wife and going back to his job as a timberman and these things that he sees and weird shit that goes on. And then he comes back and she’s no longer there, and his life just becomes this strange, dreamlike grieving situation. It really sneaks up on you, the whole idea of what the book is actually about, which is a comment on grief and mortality.

That’s been such something you’ve grappled with so much in your work. One reason why so many relate to your recent work is because we deal with those things ourselves and we’re interested by how you are processing it. So it’s interesting that there’d be a continuity there with this project.

Yeah, there are similar things that I’ve been through, and they pretty much leak into everything that I do. But it’s not that I try and write about that stuff. It’s that my boys’ presences are infused in all that I write. I find that very difficult to separate myself from. It gets easier, but it’s been very difficult. So I’ve read “Train Dreams” many times, starting many years ago, and obviously it takes on a different force with the things that have gone on in my own personal life. There’s something about the way he writes about grief that you don’t even really understand that it’s about that until, towards the end, you go, “OK, this is what this book is actually about.” There’s something that I found deeply affecting about that I can’t really even describe it — that it is both an ordinary life and a life full of wonder. Which our lives are. And the film echoes that beautifully as well.

You write in the song about “the strange and wondrous things I’ve seen, measured in truth,” and then you talk about “a tendency to pain.” You’ve perhaps striven to have that kind of balance in a lot of what you write.

Yeah, it holds all of those things very lightly, like the book. Neither the film nor the book are ever morbid. There’s something life-affirming about this devastating story. And that’s the beautiful paradox of grief, really.

Did you approach watching the film itself with any trepidation, since the book was so dear to you?

Yes, I did approach it with a whole lot of trepidation, but I was just really drawn into it. It’s its own thing; I think it’s totally different than than the book. There’s another (variation) of a major work of art that’s out there that’s connected to the book too, and that’s Will Patton’s reading of “Train Dreams,” the audio book. The audio book, I just recommend it to anybody, as the most beautiful reading of an extraordinary book. But the book is a little kind of quirkier, I think. There’s a sort of playful element to the book, and I think that the film feels more a serious look at grief, you could say. But I think they both handle the reigns very lightly on this subject matter.

Literally there are dreams in the book and film, and then you capture that in the lyrics, and you talk about “crazy dreams that go on for hours.” Do you spend a lot of time thinking about how we process loss or or relive things through dreams and that?

I don’t dream… You know, my wife dreams all the time, and it’s an active part of her existence, her dreams. She wakes up in the morning, every morning — “Oh God, I had this dream last night.” I just don’t have that. I dream through her, you could say. And a lot of her dreams are very much like dreams in the song. You know, they are about our boy, and they’re very, very beautiful and very simple, and we feel it very much a way of him finding us and kind of being with us for a while through Suzy. It’s very beautiful, the whole thing. So, yeah, we have a very strong relationship with dreams, although I personally am not the one who’s doing the dreaming. I’m very jealous of that.

Did this affect at all how you feel about collaboration?

I really liked Bryce’s score, and I noticed it when I was watching “Train Dreams,” so that’s why I didn’t really want to interfere with it. But we found a way of doing it that didn’t change the mood of the score at all. In a way, it feels, at least to me, as if the score is moving towards the song in a way. And that’s largely thanks to his beautiful piece of music. Normally, I just work with the people that I work with, Warren Ellis and the people in the Bad Seeds. I very rarely collaborate with anyone outside of my very tight circle. So that was strange and a new thing for me to do, moving out of my comfort zone a little bit to do something with somebody else. It was quite lovely.

Apart from this song, it has been a good or fruitful season for you, especially with things people are seeing overseas than they might be in the U.S. right now, like the “Veiled World” special and then the series “The Death of Bunny Monro” and your soundtrack for it. Those have been well-reviewed.

Yeah, “The Death of Bunny Monro” has done really well. People have been spent trying to make that for 20 years or something. I wrote that (novel) 20 years ago, so that’s amazing to see that be on TV. It’s a challenging series, and I think Sky were pretty courageous and allowed it to be the way that it was.

You’re touring Australia, New Zealand and various places through August of next year. It might be greedy for your U.S. to want to have you back in the States right away, when you just toured with the Bad Seeds in 2024. But are there any plans to come back to America, or is that too far off to speculate?

Me? Not the band, but yes, I am (for solo shows), yeah. I haven’t announced that, but yes, I’m doing some.

From Variety US