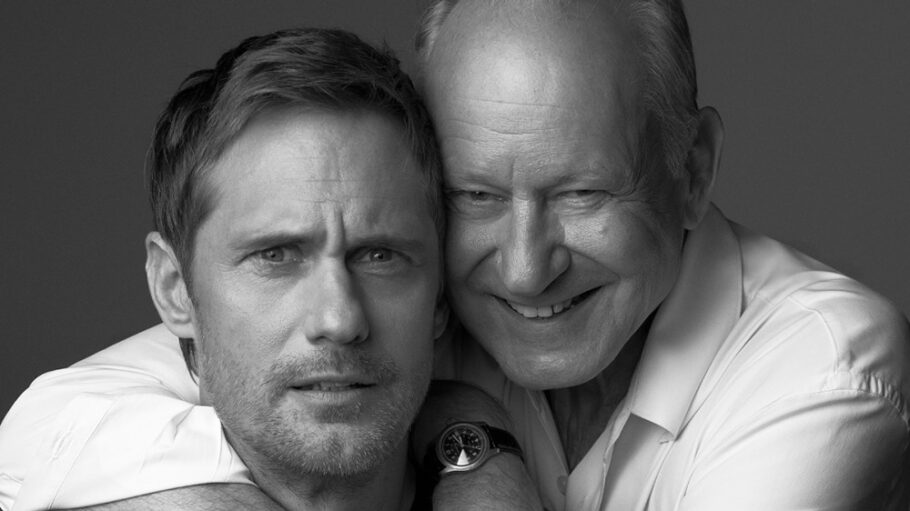

For Stellan Skarsgård, art is imitating life this fall in one sense: In “Sentimental Value,” he plays a well-known artist with actor children. The difference may be in, well, sentiment — the real-life Stellan Skarsgård has an affectionate bond with his son, Alexander (one of several Skarsgård offspring to work as actors), while Gustav Borg, the character he plays onscreen, is far more closed-off. It’s a triumphant return to the screen for the actor, who suffered a stroke in 2022. Stellan and Alexander Skarsgård affectionately rib one another at only the latest of their awards-season stops together, as Alexander promotes his own knotty and complex film, “Pillion,” in which he plays the forbidding, unknowable top in a gay BDSM relationship.

Stellan Skarsgård: When did you first want to be an actor? Did you want to be an actor? The first film you did, you were seven or something, right?

Alexander Skarsgård: Allan Edwall, the iconic Swedish actor-director, was over at our place. You guys were drinking wine. He was going to direct a film, and he needed a seven-year-old kid. I happened to be around and I happened to be seven, so he probably just asked you. Straight-up nepotism: That’s how I booked the job. I don’t even think I auditioned for it. He cast me as the lead of the movie — it’s about a bourgeoise family in the ‘30s, and it’s quite an affluent neighborhood, but his friend is from a poor part of town and ends up dying in the movie. I was cast as a lead, and then Allan found another guy who looked way more bourgeoise.

Stellan: You weren’t bourgeoise enough.

Alexander: Well, I was very skinny and looked malnourished. It made sense that I would be the dying buddy, rather than the lead.

I didn’t answer your question. I didn’t want to be an actor. Your question was when did I know?

Stellan: Maybe you don’t know even now.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

Alexander: I’m still trying to figure it out, what do I do when I grow up.

Stellan: That’s something you’ve got to wait until you’re mature enough to make a decision about, isn’t it?

Alexander: Have you landed comfortably in the decision?

Stellan: As long as I make a lot of money and have fun with this, I will do this until I know what I will do.

Alexander: You still want to be a firefighter? Never give up on your dreams, Dad.

Stellan: You were playing consumption very well. You really looked dying. The smaller role that you did was a much better role, don’t you agree? You got to die!

Alexander: It was a very juicy part. But I did not walk away from that production thinking, “This is what I do for the rest of my life.” I remember craft services was great. I got free Cinnabons, which was exciting. But that was the main thing I took away from that experience.

Stellan: It’s about the same time you told me, “Why can’t you have a normal job and work with data and drive a Saab, like everybody else does?”

Alexander: And wear a suit, goddamit, instead of your weird hippie sarongs or nothing. My dream was for my family to be normal and fit in and be like everybody else’s family. For you to have a briefcase, that would’ve been fantastic, rather than a weird tote bag that you found in India. Most people in our family are artists — a lot of eccentric, big personalities that I loved. But the early teens, bringing friends over was always like, “Oh, God,” because I wanted it to be like everyone else’s household. I was very adamant — I was going to be in a cubicle, drive a Saab, and have that beautiful briefcase.

Stellan: You did some TV series when you were in the early teens, right? And that was a disaster because you got too popular.

Alexander: I did a television film when I was 13. It got a little bit of attention — enough to make me freak out. Not that I had pursued acting up until that point, but after that, I was like, I don’t want to do this at all. I didn’t act for another eight years.

Stellan: If you work with data, you can afford to buy your own Cinnabons.

Alexander: That was what I pursued after that. But I failed.

Stellan: You failed trying to have a normal life?

Alexander: I think I did. Clearly, we’re sitting here with no briefcase.

Stellan: You went into the military — did you do that in opposition to me, to provoke me?

Alexander: Looking back, I don’t think it was an act of rebellion against you. But coming from a bohemian family, I was like, I want to find my own path. The most extreme contrast would be to go into the military. So it wasn’t a conscious “Fuck you, Dad” thing.

Stellan: I felt fucked.

Alexander: You’re a tremendous actor, Father, because I never felt that.

Stellan: I am not the kind of father who says, “No, you shouldn’t do that.” I don’t interfere with your decisions. But being a military evader like me, it felt like, “Oh, wow.” I also knew that all you eight kids have different ways of approaching everything. Maybe I’m lazy, but I think it’s best to let you do it on your own.

Alexander: How did you get out of the military? When I joined, it was semi-mandatory. But when you were a teenager, it was mandatory.

Stellan: I went to a friend who worked at a drug rehabilitation institution. And I made him write a letter to the draft board saying, “If you feel that Skarsgård is fit for military service, keep him under special surveillance because he might influence other kids. He smokes hashish.” Four hours later, I got a message from the draft: “Don’t come here. Don’t go near us.”

Alexander: You were pursuing acting at that point.

Stellan: I was working as an actor in the theater. I quit school when I was 17 because I got a theater offer in another town.

Alexander: Are you ever going to be on stage again?

Stellan: No, never. A couple of years ago, we had a reading of a play in London. The actors rehearse a little, and then you gather in the evening and read from the script to find out if it’s a good play. I had not been working in the theater for years, and I found, “My God, this doesn’t work.” I couldn’t reach the audience. I felt like I was just waiting for my close-up so I could do something. I ran out in the West End and went up and down the streets, doing voice exercises and physical exercises. I was so scared when I came back to the theater in the evening, I shook so much that I couldn’t even read the lines from the script.

When my cue came, suddenly I felt something. The voice came, and the expression came, and the feeling came from years of theater work. And I knew that I could reach the furthest away in the audience.

Alexander: When you stepped out onstage and felt that, were you bitten by the bug again? Were you feeling like, maybe it’d be fine to do something more than a reading?

Stellan: Of course, I felt this was lovely. But it’s too much work for me now — I can’t remember a lot of lines like that. But when theater is good, it’s better than anything else. But that doesn’t happen that often. When you’re working on a bad show, going down every night knowing it’s bad, you have to struggle. I’ve been enjoying learning film, learning more every day.

Alexander: That’s interesting, because I have nothing more to learn.

Stellan: When you suddenly decided to become an actor, you went to a university in New York and studied acting for a while. And then you did some small things in Sweden, but basically were going to auditions in L.A. for six years, right?

Alexander: It was 2000 — you were shooting a movie in L.A. I came out to visit, and I had just finished drama school in New York and didn’t have representation in Sweden. Your old manager was like, “Gee, I’ll send you out to an audition. Wouldn’t that be fun?” And it was for “Zoolander,” and I got a small part in the movie. Two weeks later, I’m in Tribeca shooting with Ben Stiller.

I was very naive, because I’d only been to one audition, and I’d booked it. I was like, it’s a piece of cake. You just walk in and Ben Stiller’s there and then they fly you business class to New York and you shoot. And then I realized it was a lot harder; it was many years of auditioning and not booking anything. It wasn’t down to the wire, the last group of guys — I was often cut way earlier. But occasionally, almost getting stuff was enough to keep me going.

Stellan: I felt I was bleeding with you because of this constant rejection.

Alexander: I know you were nervous going into “Sentimental Value” — about the weight of it, or your own capability of playing the part.

Stellan: You mean because of the stroke? I wasn’t that nervous, because I’d made the second season of “Andor” and the second part of “Dune” after the stroke. The directors of both helped me a lot — I was in the hospital and called Tony Gilroy and Denis Villeneuve and said, “I don’t know what’s going to happen.” They were very supportive.

Alexander: Did you feel like, “I know I can fix this”?

Stellan: I felt I could do it. I still had my voice. I didn’t know how to handle this sort of earwig thing. But with the earwig — the guy talking in my ear — must not interrupt my rhythm; I have to hear the other person saying my cue, and he has to be very fast and clear, without emotion, say the line, and then I can create my rhythm. That was complicated. I thought, “Well, maybe this is it. Maybe I won’t get any more jobs.” And then Joachim [Trier] called me.

Alexander: I remember before going into it, it was almost an existential crisis. You’ve been acting for 60 years, and then it’s like, “Is that it? Am I never going to do this again?”

Stellan: But also, I’m 74 years old now. Most people writing are much younger. They rarely understand older people. They think old people can’t handle a cellphone, walk funny and can’t tie their shoelaces. Most of the scripts that I get are someone who’s got dementia or Alzheimer’s. With all respect for those people, I don’t want to play that yet. Suddenly you’re supposed to play a certain age, not a person.

When I got the offer to do Joachim’s film, he knew that I would say yes, of course. I invited him to Stockholm to dinner. I insisted on paying, because I said, “I don’t want to owe you anything, you cocky fucker.” I got the script and read it and it was fantastic, very sexy and beautiful. I knew I would say yes, but I still didn’t say yes immediately.

Alexander: Why did you not commit?

Stellan: He was being a little shy himself. We were dancing around each other like two dogs sniffing each other’s asses. “How does your feces smell? Can I trust you?”

Alexander: Clearly his feces smelled pretty good.

Stellan: His process is brilliant, and he had written the role basically for me. Getting a role like that, one of the best roles I’ve ever had, it was magic to me. The feeling on set is beautiful.

Alexander: Similar to [Lars] von Trier?

Stellan: Yes, but the outcome is different. The Trier brothers have this similar thing that, for whatever is produced in front of the camera, you have to let go. It has to be spontaneous. And you have to allow accidents to happen — the weirdness that you can’t plan.

When you got the script for “Pillion,” did you know [writer-director Harry Lighton] before?

Alexander: Not at all. It was kind of out of the blue.

Stellan: What was it that caught your eye?

Alexander: Well, it was a love story set in the world of BDSM, which intrigued me enough to open the script, at least. As soon as I did that, I was hooked. I was really surprised — I didn’t expect it to be so tender and sweet and funny and awkward. It was such a rich, beautiful script. I had a conversation with Harry and was incredibly impressed by his vision, how he wanted to tell this story.

Journalists have been like, “Oh, it must have been such a scary decision to jump onboard. It’s a kinky gay biker movie by a first-time filmmaker. Why take that risk?” But if a script is phenomenal and you believe in the director, it’s not scary. I am scared if I’m not crazy about the script or if I have reservations about the filmmaker. I really believed in Harry.

The elephant in the room here, Dad, is that we’re both nominated for a Gotham Award in the same category. [At this year’s Gotham Awards, held on December 1, both Skarsgårds lost their category to “Sinners” actor Wunmi Mosaku.]

And people believe that it’s all going to be chummy and dad and son support each other. Which we are to a certain extent.

Stellan: There are limits.

Alexander: Now we’re up against each other.

Stellan: Now it’s gloves off.

Alexander: “Sentimental Value” — a beautiful film. You play yourself, right? An absentee father?

Stellan: That’s an insult.

Alexander: The smear campaign has begun.

Stellan: You don’t have to smear “Pillion.” It smears itself.

Alexander: What do you think of my performance in “Pillion”? Was it worthy of — I don’t know — a Gotham Award?

Stellan: It’s very hard to predict whether it is worthy of a Gotham Award or not. But it was a very moving and beautiful film, and I had a lot of fun seeing it. You showed me sides of you that I had never seen before.

Alexander: Literally.

Stellan: Literally.

Alexander: But it was a really incredible weekend we had at the Telluride Film Festival. Usually, you dip in for 48 hours and it’s press junkets and screenings and then you’re out. But this was lovely, because all we had to do was one Q & A each. So we had time to hang out, get drunk together, be hungover together, see each other’s movies. Watching “Sentimental Value” with you next to me was something I’ll never forget. Because knowing what you went through in the years leading up to it … It was a 9 a.m. screening, so I was a little hungover, very fragile and emotionally open.

Stellan: It really gets to people when they’re slightly fragile, right?

Alexander: Yes.

Stellan: Like any film does.

This is a conversation from Variety and CNN’s Actors on Actors. To watch the full video, go to CNN’s streaming platform now. Or check out Variety’s YouTube page at 3 p.m. ET today.

From Variety US