In an industry where even “Weird Al” Yankovic has a movie about his life story, it’s about time the Boss got his due. But “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” isn’t just another assembly-line biopic — and that’s a blessing — in that it focuses not on the blue-collar troubadour’s glory days, but on the darkest chapter of his career: the narrow, near-suicidal period in which he stepped back from the success of his tour for “The River,” returned to his working-class roots and wrote what many consider to be his greatest album, “Nebraska.”

Too many music-centric movies subscribe to the same formula, dramatizing the arc whereby talented nobodies get discovered, shoot to stardom and then stumble with drugs and infidelity when fame becomes too much, only to be redeemed (“Rocketman”) or buried (“Fade to Black”) in the end. It’s an exasperating genre in that it forces some of the planet’s most unorthodox personalities into a reductive, overly moralistic mold, the obvious solution for which is to find and focus on a dramatic segment of their larger life story.

As the man who made “Crazy Heart,” about the last hurrah of a grizzled folk legend, writer-director Scott Cooper intuitively recognizes a compelling hook when he hears it. The spiritual crisis Springsteen faced around the writing of “Nebraska” seems as good an angle as any, though the filmmaker assumes we already know and care more about that record than is reasonable. It’s hard to imagine the under-30 set recognizing the significance of a star of Springsteen’s stature making an album in his bedroom — not his first, but his sixth, which made it all the more radical — effectively paving the way for the DIY indie-rock sound that followed.

But without that background, it’s a fairly dull story.

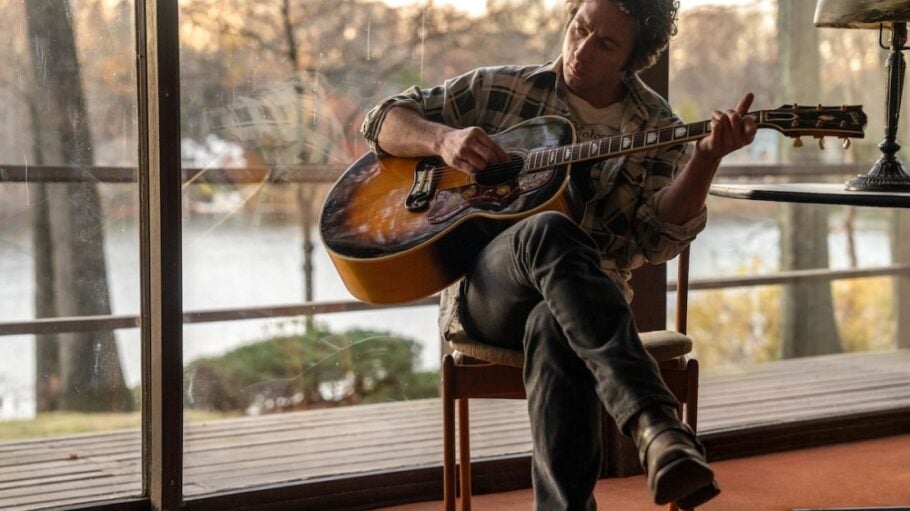

Compared with figures like Michael Jackson and Prince (heck, even Yankovic), Springsteen’s ruggedly handsome, man-of-the-people persona should have made him a reasonably easy artist to cast, and yet, it’s taken this long to find the right guy for the part. It requires a star to play a star, and an actor to access the Boss’s more introspective side, and “The Bear” sensation Jeremy Allen White slips easily into the worn denim and sleeveless T-shirts that were Springsteen’s signature. More importantly, he does all his own singing, capturing the scratchy, soul-searching baritone that marked that period of his career.

We first meet Springsteen onstage, soaked in sweat and giving one hell of a show — already the burgeoning rock god, determined to shake the “new Dylan” refrain — but that’s the last we’ll see of Bruce’s contagious charisma for nearly 100 minutes, as the star does something shocking for someone poised to rocket to the moon: Instead of immediately following that up with “Born in the U.S.A.” (a monster success that couldn’t have existed without first passing through the noncommercial terrain of “Nebraska”), he goes home … looking for what exactly?

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

That’s the central mystery of Cooper’s film, which he drew from Warren Zanes’ excellent deep dive into the making of “Nebraska.” In his book, Zanes identifies the album as a turning point in music recording history, a stripped-down collection of intimate sketches, captured on a four-track TEAC 144 and released more or less as it was, imperfections and all — without backup from the E Street Band, relying on Mike Batlan (Paul Walter Hauser) to mix and a water-damaged Panasonic boombox for playback.

Prior to 1981, the equipment didn’t exist that would have allowed artists to record at home, and even then, it wasn’t Springsteen’s intention to release those tapes. That’s what makes them so special: He didn’t know he was making an album, which is what gave “Nebraska” its purity (especially coming from such a notorious perfectionist as Springsteen). Well, that and Springsteen’s insistence that it be released with no radio edits, no singles, no press and no tour. As Zanes put it, “The album made it impossible to use the word ‘sellout.’”

The movie doesn’t do nearly enough to contextualize this breakthrough, however. It shows all the headaches Bruce’s tape caused for manager Jon Landau (Jeremy Strong) and recording engineer Chuck Plotkin (Marc Maron) and his cadre of studio pros, but the technical side isn’t nearly as dramatic as it sounds, and there’s only limited interest in watching White navigate the icon’s first serious bout of depression. That is, unless one understands just how much that record represents to the next generations of musicians and why.

As the film depicts, right after “The River,” Bruce rents a house in Colts Neck, New Jersey, where he watches Terrence Malick’s “Badlands” (based on the Charles Starkweather crime spree), reads Flannery O’Connor and listens to Suicide’s hard-on-the-ears debut album — all inspirations for “Nebraska.” But what he’s really doing is coming to terms with the stardom that awaits; he revisits his old haunts, where former classmates now look up to him (the precise feeling that chip-on-their-shoulder fame-seekers so often crave) and a casual acquaintance’s kid sister hits on the singer.

Faye Romano plays this composite character, Odessa Young, an earnest single mom who never left home, but gets her wish of dating the guy who did. Her romance with Bruce goes nowhere but reveals layers of Springsteen — that he wasn’t celibate, for starters, but also the slightly callous, self-involved way that writing “Nebraska” took priority in his mind.

Returning to his old turf was inevitably triggering for Springsteen, forcing him to confront unresolved family issues. “Adolescence” star Stephen Graham and Gaby Hoffmann play his parents, one drunk and distant, the other in need of defending, who haunt him via trite black-and-white flashbacks (presumably essential, considering how much Springsteen’s childhood informs “Nebraska”).

There’s a stagnant feel to Bruce’s time back in Jersey, during which we watch him jotting down lyrics and test-driving songs like “Mansion on the Hill” and “Atlantic City.” Cooper captures the moment when Bruce crosses out the “He” in “Nebraska” and decides to relate Starkweather’s story in the first person instead.

It’s rare to see a producer have his client’s back the way Landau does (though the role isn’t substantive enough to take full advantage of Strong’s strengths). His support effectively removes what conflict such a creative risk represents — the pushback loosely embodied by David Krumholtz as Columbia exec Al Teller, who expects a follow-up he can sell.

As “Nebraska” comes together, we realize this wasn’t pop music Springsteen was making, but something deeply cynical about the country Ronald Reagan and the mainstream media believed he was cheerleading. Rather, he delivered a downbeat ballad about all the ways the American dream had fallen short. This is how such unvarnished truth found its way to the people. The rest — what it represented to every soul it touched — is for you to sort out.

From Variety US