“The best thing is to let everyone know that I’ve read it and they needn’t pussyfoot around it,” he says. “I know that I’ve been chastised.”

For his latest role in “The Critic,” it’s McKellen who is delivering the blistering assessments as Jimmy Erskine, an acid-tongued theater reviewer who yields a corrosive influence over a struggling actress named Nina Land, played by Gemma Arterton. He’s a Mephistophelian figure — one who exchanged his moral compass for great orchestra seats.

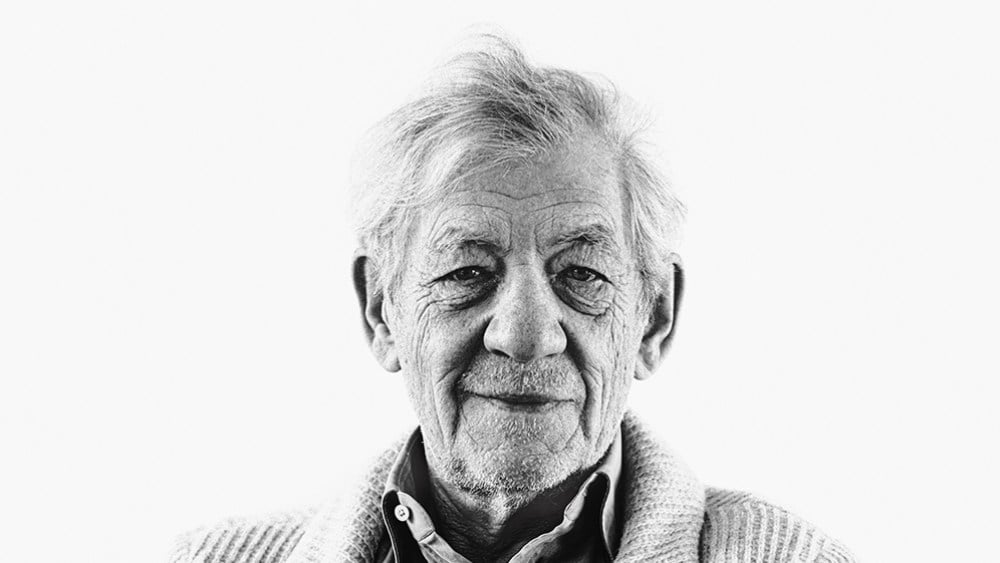

Alfred Enoch and Ian McKellen in “The Critic”

Sean Gleason

“Often the devil has the best tunes and the best lines, and it’s fun to play an outrageous man who clearly has some emotional problems,” McKellen says during a Zoom interview from his London home. His gray hair is a thicket of indifference, he’s nursing some stubble and chain-smoking, but despite his informal appearance, he still seems so elegant. Blessed with a stentorian tone that makes him perfect for classical heroes, every one of McKellen’s asides and utterances arrives with an air of profundity.

“The Critic” will have its world premiere at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival, where the producers will try to sell it to a studio. If the film lands a deal, McKellen’s performance will have a lot to do with it.

“It was an intriguing script, tending toward melodrama,” he says. “If the audience doesn’t believe in what we’re doing, then they might find some of the action a bit overwrought. It was a tricky balance to strike.”

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

As we talk, I notice that hanging behind him is a small snapshot of Laurence Olivier, outfitted in a bowler hat from the film “The Entertainer.” “He meant everything to my generation,” McKellen says. “He was the big ever-present spirit over the British theater.”

There’s a scene in “The Critic” where Erskine talks to Land about the ineffable quality that performers like Olivier are blessed with — the rare ability to bring a character, with all its contradictions and foibles, to glorious life. He describes their “capacity to conjure the sublime” and ascribes it to “the courage to give of the self entirely.” McKellen, who has embodied heroes and villains, great kings and lowly strivers, kindly wizards and mutant overlords, so memorably over the years, has it too. But he’s as hard-pressed as Erskine to describe how he pulls off these transformations. He wasn’t, he notes, formally trained, arriving in the theater by way of Cambridge, where he majored in literature.

“I’ve never learned Meisner or any technique of acting,” McKellen says. “I didn’t go to drama school. I’ve often wished that I did have a foolproof approach to how to prepare. Each play or movie stands by itself for me. And every time I begin with this terror of just ‘Here we go again, making the same mistakes.’”

For McKellen, it all starts with the text. He pores over his scripts, hoping to excavate clues about his characters’ motivations while sketching their backstories. Then he begins to think about exterior elements — how they move, the clothes they wear, the inflection of their voice.

McKellen and Brendan Fraser in 1998’s “Gods and Monsters”

©Lions Gate/courtesy Everett Co

“So much work happens before Ian ever gets in front of a camera,” says Bill Condon, who directed McKellen in four films, including “Gods and Monsters,” which won him an Oscar nomination. “At first, it’s a lot of sitting around talking about the screenplay, and then he starts to build from the outside in. And the conversation becomes all about props and blocking before he starts homing in on something more precise and expressive to find that thing that unlocks it for him.”

McKellen relies on sensitive directors to nudge him toward these epiphanies. “I’m very dependent on someone from the outside saying, ‘This is what I’m receiving from you,’” he says. “I would define a good director as an honest one who says, ‘Look, this is mostly not working. But, Ian, at that moment where you decided not to sit down, you were absolutely the character.’ If I can then remember that moment and what it felt like and how my body was positioned, I can take advantage of that sensation. Then it starts to spread throughout my DNA.”

And he’s blunt about the filmmakers who have impeded the muse from appearing. On “The Keep,” Michael Mann’s ill-fated 1983 horror film, McKellen was forced to endure hours of makeup to make him seem older. He calls it his worst moviemaking experience.

“Michael Mann said to me, ‘You’re playing this Romanian.’ So I went to Romania to scout it out, and I learned how to speak with a Romanian accent. Then on the first day of shooting, Michael told me he wanted me to speak with a Chicago accent. Well, I couldn’t do that, and it got worse from there.”

Most of the early part of McKellen’s career unfolded onstage. He didn’t become invested in film work until the late 1980s and ’90s, and there are reasons why he took the leap so late. He thinks his acting was initially too presentational and lacking in subtlety.

Two pivotal moments started McKellen thinking about performing differently. The first was a stripped-down 1976 production of “Macbeth” that found him playing the murderous general opposite Judi Dench under the direction of Trevor Nunn. The show was performed in the round, for an intimate audience of roughly 120 people.

“The joy of that was there was no need to project a performance and tell people far away what you’re thinking, because they could see every movement that your face made,” he says. “They were so close. After that, I never wanted to work in a big theater again where I would have to do that sort of display acting.”

And the second and more consequential change came when McKellen decided to come out as gay in 1988, a declaration he made to protest Margaret Thatcher’s government’s embrace of a series of laws across Britain that prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality” by local authorities.

“Almost overnight everything in my life changed for the better — my relationships with people and my whole attitude toward acting changed,” he says.

Before he went public with his sexuality, McKellen preferred to transform himself to play characters. After, he drew more on his personal connection to a part. “The kind of acting that I had been good at was all about disguise — adopting funny voices and odd walks,” McKellen says. “It was about lying to the world. I was no longer in the situation where I was running along beside the character explaining it to the audience. I just became the character.”

McKellen began noticing a difference in his work. If he needed to cry onstage, for instance, he found the tears flowing effortlessly in the wake of his announcement. He was more emotionally available, more present. And if that change hadn’t taken place, he doubts he could have made the move to film, with the camera exposing and magnifying any wrong note.

“People who are not gay just simply don’t know how it damages you to be lying about what you are and ashamed of yourself,” McKellen says. “I was brought up at a time when it was illegal for me to have sex with a man. And that was not that long ago.”

McKellen and Gemma Arterton in “The Critic”

Courtesy Sean Gleason

In fact, “The Critic” unfolds during the 1930s, and Erskine, who is gay, finds himself on the brink of being fired after the police pick him up for soliciting sex. To keep his job, he resorts to blackmail. McKellen says that the secrecy and threat of scandal that Erskine has to endure is what pushes him to the dark side.

“The Critic” director Anand Tucker thinks that his leading man’s intimate knowledge of the psychological impact of living in that kind of intolerant society helped shape his performance. “I don’t subscribe to the idea that you need to be gay to play a gay part,” says Tucker. “But in Ian’s case, there’s something about his own lived experience that allowed him to bring a kind of urgent truth to the role. He had a deep understanding of what it means to be an outsider who is shunned for the truth of who they are.”

It’s a part that McKellen wasn’t originally supposed to play. When “The Critic” was first announced, Simon Russell Beale was cast as Erskine. But after COVID delayed production, Beale was busy with other projects. When I ask McKellen if it bothered him to be somebody’s second choice, he makes a gesture as if to swat away any suggestion of offense.

“I don’t think you’re ever the first choice,” he says, noting that a lot of other actors were offered his part in “The Lord of the Rings” before he got the call to journey to Middle-earth. “I certainly wasn’t the first choice for Gandalf. Tony Hopkins turned it down. Sean Connery certainly did. They’re all coming out of the woodwork now, and I hope they feel silly.”

“The Critic” comes at a busy period in McKellen’s professional life. He’s set to appear in an unusual film adaptation of “Hamlet,” playing the young prince despite being an octogenarian, and he’s just recorded a voice role for a new Seth MacFarlane show. Onstage this year, McKellen is appearing in a comedy, “Frank and Percy,” which he hopes will be adapted to film. Now that he’s entered his ninth decade, McKellen says he’s constantly reminded of his mortality, but hesitant to contemplate something as dramatic as retiring.

“Retire to do what?” he says incredulously. “I’ve never been out of work, but I’m aware that any minute now something could happen to me which could prevent me from ever working again. But while the knees hold up and the memory remains intact, why shouldn’t I carry on? I really feel I’m quite good at this acting thing now.”

That’s not to say he’s immune to the rare bad review. Early in previews for “Frank and Percy,” when McKellen says he was “insufficiently acquainted with the text,” a critic came to see the production. In his review, he faulted McKellen for forgetting his lines. “Instead of understanding that this happens from time to time, this critic says it was evidence that it was time for Ian McKellen to stop acting,” he says. “Maybe I should challenge this man to a podcast where we could debate it.”

Then McKellen reconsiders the wisdom of such a move.

“Perhaps that’s not a wise thing to do,” he reflects. “It might just draw more attention to it. After all, I’ve long ago made my peace with critics.”

From Variety US